At times I don’t know where I should begin,

Whether to make someone scream loud or grin,

But I have set my brain on the matter

And found that readers grow sick of splatter,

So I need some new approaches to win.

A problem with being a… distinct… messed up… take your pick… individual lies in finding people who are like-minded, and after forty years on the planet, I have reached the conclusion that not enough like-minded people exist to be found.

Yes, I have found like-minded people through artworks, signs of lives and experiences like my own. Throughout the years I have been able to cobble together enough media from the “popular” culture to sustain me, but I never gave enough thought to why everything I liked got labeled with terms such as “alternative,” “fringe,” and “cult.” Actually, I gave a ton of thought to such labeling, writing an undergraduate thesis about the marginalization of popular forms in comparison to “high” or sanctioned-by-the-rich culture and then writing a dissertation about horror fiction, the bastard stepchild of literature, a genre that virtually all the greats have dipped toes in but no one wants to own as part of the mainstream’s backbone. I taught college classes on the alternative, the fringe, and the cult, showing mainstream students what’s going on out in the weird edges of their universes, and people usually (not always) rolled with what I sent their way, as college is a time for experimentation, after all. But what never quite sunk in for me, through all my research, teaching, and publication about the weird stuff, is that the weird is weird primarily because of a numbers game: it’s outsider art because not enough people want it on the inside, and the weirder it is, the fewer people want to deal with it.

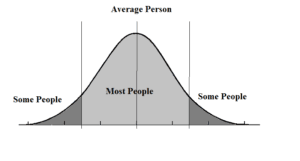

Maybe in a few centuries, people will look back on some of the weird stuff as great, but in the moment, most weird stuff isn’t the charming, middle-of-the-road stuff that the middle of the bell curve embraces. Normal people, which is the vast majority (by definition!), don’t want the abnormal stuff, and I have finally begun to understand that. To produce stuff people want, I have to stop assuming people want what I want. I’ve got to temper my wild weirdness with a heavy dose of the normal. All great artists know they must cave to conformity—or they do it instinctively, as the mainstream is in their bloodstream. I’m not saying I’m great, but I’d like to be better, and what might have been missing from my oddball art all these years might have been a heavy dose of crowd-pleasing. Instead of poo-pooing the crowd-pleasing tidiness and happiness that define mainstream narrative, maybe I should have been including more of it, as there just isn’t enough crowd out there that isn’t looking to get pleased.

I am not lamenting. In fact, although I have yet to see whether it’s going to go belly-up or go through the process of fetching an agent, publisher, and a mainstream audience, I not-too-long-ago finished my first novel with the philosophy of trying to please crowds who don’t all share my own particular mindset. The novel is called The Vengeance of Galatea Starcrusher, and though it has some horrific elements (from the first paragraph, my prettier protagonist identifies herself with Frankenstein’s Creature) it’s my first effort in many years that is pretty unequivocally not a horror novel. It’s science fiction, or more precisely science fantasy, and a lot of it is downright silly, going for absurd levity in places where before I might have sought a grotesque sucker-punch. I don’t think I’m as funny as Douglas Adams, but at times his ilk is the inspiration, and otherwise I’m riffing on space opera adventure from TV and movies circa Star Wars and beyond as my heroine kicks lots of butt on her way to hunting down and taking vengeance on her slimy, no-good creator. There are explosions. Lots of explosions. There’s chemistry with sidekicks. There’s a romantic subplot. Did I mention the explosions?

If people see in their heads anything like what I saw in mine, they’ll have a righteous adventure. They’ll have fun. They’ll SMILE all the way through one tidy happy scene after another. One or two scenes might make them gasp in horror, but they’ll come back to the adventure all the readier for the next tidy-up, which I do indeed provide. The writing experience was a blast; I hope the reading experience is, too. As I wrote, I imagined not what my ideal audience would want to read, but what general audiences might want to read. I didn’t always spit out exactly what I thought the normals would want. I’m still me, and the book is definitely a product of my warped imagination. But what produced it was an imaginary negotiation between me, sitting out on the edge of the bell curve, and other people I don’t know too well, sitting up high in the fat bell’s curvy center. If we can all get along, I’ll have a successful book of a sort very different from everything I’ve ever published.

That’s the hope, anyway. I can’t just flip a switch and become normal, nor would I want to, nor would readers be likely to respond well if I did. People don’t pick up novels to experience pure normality: they want to experience something, well, novel. The art of writing fiction is an act of balancing the outré with the familiar, titillating with the former and soothing with the latter, so that the people in the center of the bell curve feel like they’re glimpsing the outer edges, and the people further out feel like they’re being served, too. A good book needs extremes, but the extremes shouldn’t point all one way to suit most readers. An extreme of despair should have at least a glimmer of extreme hope. A younger me never would have admitted that, but my current thinking—thinking that powers through the aching desire to believe a critical mass of readers might just like to stew in darkness for 100,000 words—recognizes that people read to get away from the grinding conditions of lives that can often seem more than dark enough. Even dispositions that embrace the dark side need perks. Mine does. The artist’s job is to meet the needs people seek to have fulfilled through art, and heck if those needs don’t include a lift up more often than not. A long-time devotee of the arts of horror and dark fantasy finds that a tough pill, but then again, even most horror stories have marginally happy endings. I guess we know why that is. People’s need for those stories includes need for those endings.

Stephen King got most of his darkest stories out of his system when he was young: the bleakness of Carrie and Pet Sematary, hits certainly, hasn’t shown up as much since he got sober and became America’s perennial bestseller with a tendency to write about magic children saving the day. Writers in the grip of mental illness who described the world as the horror they saw—such as Poe and Lovecraft—did not come to good ends. The positive of powering through the realization that writing is a compromise not with the artist’s audience of choice but with The Mainstream is, quite simply, survival. King’s gift is that he can figure out what the mainstream is, what its tolerances are. I don’t know if I have that gift, but the challenge of trying seems worthwhile—for me as well as for any other author who wants to communicate a vision to minds outside the narrow band defined as being like her or his own.

Interesting posting. I hope you have success with the novel.

Reading what you wrote made me think about the way some people seem to think about Shakespeare: namely, that he had a metamorphic, everyone-and-no one personality; or that there was a certain elasticity to him. This is the way I think about certain actors’ abilities: that they have the ability to expand or grow their personalities, becoming-other, becoming others — others who might seem some distance away from where they might consider their own core personalities to be. Nevertheless, they’re able to expand that nucleus of identity or personality, and, in acts of benign appropriation, grow to cover or encompass these “other” selves.

At any rate, that’s a roundabout way of saying I think it’s really nice that you felt comfortable broadening your range, perhaps stretching yourself (or connecting with less-traveled territories of your self) to do so. The fact that you had a blast, that you were able to muster the desire and energy to write a whole novel, implies that you were drawing on “authentic” impulses, that you were not betraying yourself to produce a paint-by-numbers hack job for the mass market.

I appreciate the references you make to outsider art, to Poe and Lovecraft. If I have my facts straight, Poe and Lovecraft died in relative obscurity (as you write: they “did not come to good ends”); they achieved “success,” a real following, only posthumously. It’s interesting to me, in this connection, to think about writers and artists like Emily Dickinson or Henry Darger, who not only did not find an audience in their lifetimes, but didn’t even try. I might have thought that such pessimism or despair about the possibility of communicating their visions would have impeded their creative drive, blocked their output, and dried up their desire; but apparently not. What do I know?… At any rate, the vicissitudes of creativity, personality, and desire are fascinating, and your posting gets us thinking about them. Thanks.