Dario Argento has said in several interviews, including the one I had with him, that he saw no need for a remake of Suspiria (1977) and was generally opposed to the idea. I’m generally in favor of remakes of films I like, but I took Argento’s point. Remakes can’t harm their sources, and they might do impressive things with already-proven concepts—however, I assumed that a remake of Suspiria would suck. Argento’s Suspiria doesn’t offer much in terms of story or character to work with; in its greatest moments, it is almost pure style. In remaking such a film I saw a strong temptation to imitate, but I saw little room for productive play. In other words, I didn’t see where a remake could go, so I expected it wouldn’t go very far or accomplish very much.

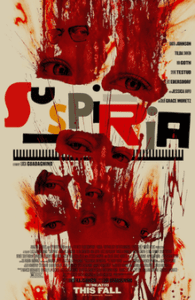

I am happy to say I was wrong about Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria (2018), which manages excellence by straying far from its namesake in some respects while staying tethered at key points. The look, sound, and pacing demonstrate the relationship succinctly. In place of Argento’s shocking palette of primary colors and assaultive sounds by the prog-rock band Goblin, the new Suspiria offers hypnotically drab greys and browns and the lulling experimental tones of Thom Yorke. The two approaches are almost inversions of one another, but they both result in dream-like atmospheres, in nightmarish worlds where witches seem likely to lurk.

Attached to Argento’s assaultive aesthetic is a tendency to pile one bizarre or violent set-piece onto another, leaving little room (or need) for character and story and allowing the film to come in at a tight 98 minutes. Guadagnino’s more meditative approach is almost an hour longer, 152 minutes, and it uses that time to provide what the earlier film denies. The new film uses the older film’s characters’ names and gives many of them the same or similar roles in a famous Dance Academy, but for a setting it trades in Freiburg and the fairy-tale-archetype-filled Black Forest for 1977 Berlin, which has a hard and specific reality underscored by news reports about terrorism and many lingering shots of the Wall. In their new setting, characters start over, developing backstories and nuanced emotional relationships that their more archetypal counterparts wouldn’t recognize. Susie Bannion (Dakota Johnson) is still an American newcomer to the Academy, but now she’s an untrained former Mennonite from Ohio who has issues with her mother that inform several dimensions of the film. Her backstory is perhaps especially important to her relationship with Madame Blanc (Tilda Swinton), still the functional leader of the Academy and now a dark maternal figure for Susie. No longer campy and two-dimensional, Madame Blanc is prominent in the post-World-War-II dance world, having given the definitive performance of Volk (“people,” a politically suggestive title if there ever was one) in 1948. She treats Susie at times as a daughter and at times an apprentice, grooming her to take the role she once defined on stage and preparing her for a different role in a witches’ conspiracy.

What the witches—the teachers who run the Academy— are conspiring about is exceptionally vague in Argento’s film. Argento keeps their meetings offscreen (we overhear bits), but Guadagnino shows the coven in session, casting votes and revealing divisions as they choose either Madame Blanc or Helena Markos (also Tilda Swinton), the unquestioned head in Argento’s version, to go on as leader. Guadagnino’s witches are searching for a young woman to play a part in a ritual that somehow sustains the coven, which in turn sustains the women within it (the coven has protected the women through World War II and other catastrophes). The exact nature of the ritual is mysterious at first, but it does become clear. If, as several critics have argued, the earlier film’s coven provides a murky view of authoritarian power and violence, the new film imagines such power wielded by and for women who have specific goals—but their power is unstable. Resolving this instability becomes a major motivator for the plot and allows for multiple conflicts to unwind at the conclusion, providing an ending far grander in scope than the earlier film’s.

A central question for any viewer coming from the graphic violence of the 1977 Suspiria is likely, How does the witches’ power look on screen? The infamous opening sequence of Argento’s film, which culminates in the gruesome deaths of two young women in glorious Technicolor, is gone, but the 2018 Suspiria is anything but tame in its depictions of violence. Whereas Argento relies on camera movements and editing to suggest magic, Guadagnino exploits his source material—dance—and makes physical movement the stuff of spellcasting. Thus in one of the film’s most memorable and cringe-inducing sequences, Susie tries dancing the role Madame Blanc defined in Volk, and, as she channels the witches’ will, each of her jerky motions results in violent bends and breaks in another young woman’s body.

At other moments, touching and hand motions pull off magical feats—bones shatter, arteries explode. While not as vibrant or elaborate, the violence of the 2018 film is just as extreme, and it’s located at the heart of the women’s profession, linking their physical power to their supernatural power. In this version, then, witches’ power—and perhaps women’s power—is deeply embodied, and their politics are literally and figuratively a dance that can break bodies apart. The breaking of bodies recurs in the setting, a broken Berlin, and makes resolving instability in the coven (and the larger political world) more urgent. The film’s trajectory drives toward a unity and stability whose cost is purification through violence, a heavy imprint of the fascism that the coven’s exercise of power ultimately reflects.

If the power the witches wield is ultimately fascistic, it is a sublime alternative to the power on offer by the patriarchy. Men get little representation in the 2018 Suspiria. Two police detectives stop by the Academy to investigate and get completely brain-wiped by the witches (who stop to fiddle with one of their absurd-looking penises just for kicks)—these men are a joke. The important male character is Dr. Klemperer (also played by Tilda Swinton), a psychoanalyst who makes the mistake of dismissing Patricia (Chloe Grace Moretz), a student who flees the Academy and its witches at the beginning of the film, as delusional. Years earlier, he also dismissed concerns about Nazis pressed by his lover Anke (Jessica Harper, who plays Susie in Argento’s film), which caused him to lose her. He sets off on parallel investigations, searching for Patricia and Anke, and as a result he gets caught up in the witches’ conspiracy, taking on a role that demonstrates the relative weakness of psychoanalysis and male judgment before the power of the women who lure him into their rites. Suspiria (1977) and Suspiria (2018) are nightmares about witches, and thus they are nightmares about powerful women. The more recent film uses Dr. Klemperer to show how utterly a man might be diminished by the consolidation of a nightmarish form of female power, diminished not just in the present but in the revelation of a lifetime of impotence.

On the surface, Guadagnino’s Suspiria looks and sounds almost unrelated to Argento’s, and a viewer looking for a repeat of Argento’s masterful sensual assault will leave the new film disappointed. What I found in the 2018 version is a film invested in the earlier version’s DNA—nightmarish reflections on power—combined with characters and storylines well-worth following. In addition to not wanting a remake of Suspiria, Argento has expressed dissatisfaction with contemporary horror. I don’t know if he has seen Suspiria 2018 or gone on record about it, but I think if it were a film of a different name, he might like it. It takes the art of horror film seriously, and it gets impressive results. That’s Argento’s legacy, and Guadagnino’s film, for all its deviation from Argento’s templates, fits perfectly.

Comments are closed.