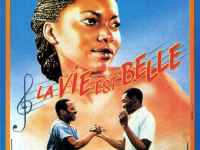

The University of Louisville kicked off the 2012 – 2013 Postcolonial Film Series today with La vie est belle (Life Is Rosy, 1987). Not knowing a lot about African film–or Africa, for that matter–I didn’t really know what to expect beyond music with infectious rhythm. As a result, catching my feet moving without conscious volition didn’t surprise me. Since Dr. Beth Willey, a specialist in postcolonial theory and African literature, chose the film for the series, the postcolonial overtones didn’t surprise me, either. What I didn’t expect were the ways in which the music points toward the film’s layered cultural resonance. I spent much of the movie listening to my brain, but I think my feet were actually more in tune with the film’s significance.

My brain told me that the film’s narrative had a lot in common with European narrative traditions. Dr. Willey pointed out, and I agree, that the story of lovers who have to work hard to get their couplings sorted out is classic Shakespeare. During the movie, though, Jane Austen was more present to me than Will–no character in the film seems untouched by the “amorous effect of ‘brass‘”. In fact, early on I felt really uncomfortable with a reduction of people, especially women, to monetary value, a relationship literally written on the wall as a woman chalks rental prices outside people’s homes. Thinking about the horrific results of the myth that having sex with a virgin can cure HIV, I shuddered as a mystic counselor in the film advised a rich man to restore his potency by pursuing a virgin girl. The traffic in women, and in some cases infant girls, has reached deadly new lows, and I didn’t like the idea of a film promoting such exchanges in the guise of romance.

The film doesn’t endorse all the cultural mores it reflects, however, and as it unfolded, I felt a growing critical awareness of the love-money link that Austen herself might well applaud. Indeed, just as the tension in Austen’s novels often comes from the perilous positions of young women who must rely on marriage for their economic survival, the tension in La vie est belle stems largely from the economic consequences of mating and dating. And in the context of sub-Saharan Africa, where polygamy is common, marriage isn’t the resolution it is (or at least seems to be) in Pride and Prejudice. The same man who has police throw an alleged thief in the trunk of his Mercedes also has the power to make his wife compete with a new bride decades her junior. In the end, the older wife has to apologize for being jealous because she hangs out too much with “liberated women,” and though the man who rides in the back end of the Mercedes gets the girl that the rich man wants, it’s only after he has proven his own economic viability as the right sort of musician (i.e., the sort of musician who gets paid). Even though lovers come together, brass wins the day: as characters explain more than once, when you don’t have money, life doesn’t seem as rosy as it’s supposed to be.

So that’s what my brain told me as I watched, but all that thinking about Shakespeare and Austen seemed to impose an Anglo-European paradigm on a film I was supposed to see in a postcolonial light. Was I colonizing the film with my English-major training? Fearing that I was, I looked to the film’s form, which didn’t immediately offer any comforting resistance to imperialistic conventions. The compositions and editing are classic Hollywood in their balance and continuity. When I looked closer, though, I noticed that almost every shot involves some kind of movement–the camera moves, the figures move, or both. Then I realized that the cinematographic movement and my feet had a lot in common. I’d have to see the film again to be sure, but I’d almost swear that at times the frame bounces with the rhythm of the onscreen performers singing about life’s rosiness. Supporting the Euro-conventional narrative and Hollywood-conventional style, then, are sonic conventions and spirit from traditions that make Shakespeare seem like a toddler. Even as a lead character discusses his ambitions in electronic music, he never gets far from the traditions that technological instruments merely give new shape. In fact, technological instrumentation in the film is manifold: a young woman pursuing an education longs for a typewriter people refer to as her “instrument,” and women and men alike thrill at the prospect of a new electronic oven that can cook three chickens at once. This technology doesn’t seem like a tool of the colonizer in danger of wiping out traditional cultures. Like La vie est belle, a story told through an electronic medium, the tech gives the culture new expression.

The expression is not unaffected by the technology’s history and origins. Like the Austenian narrative, the film form carries the impression of the colonizer, and so La vie est belle is, in the true postcolonial-theory sense, hybrid. Hybridity can be both good and bad in its effects on colonized peoples, but in La vie est belle, it’s at least good in that it enables a film that is as intellectually satisfying as it is physically moving. I’m not suggesting an alignment of colonizer/colonized with mind/body, where the colonizer has all the smarts while the colonized bears the burden of physicality. I’m saying that the best ideas I have about this film–the best thinking I’ve been able to do–started with my feet.

Comments are closed.