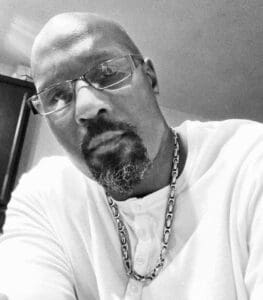

Some call him the king of hardcore horror. He certainly mixes extreme imagery with intelligent prose and poetry like few others do—or could. I am proud to present an interview with the brilliant and devastating storyteller and poet Wrath James White.

Poisoning Eros (with Monica J. O’Rourke)

Sometimes life is unfair. Sometimes life just plain sucks. You do what you can to get by, but sometimes even that isn’t enough.

Meet Gloria, aging porno star, drug addict, failed wife and mother—seduced into a monstrous world of depraved sex and violent deceit, battling to save her immortal soul and that of her only daughter from Inferno … and you thought your life was hell.

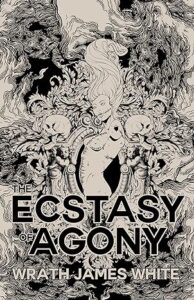

The Ecstasy of Agony

The heavyweight of hardcore horror returns with ten hard hitting new short stories and seven brutal epic poems exploring the darkest soul of humanity and the cruelty of life without pulling punches. Wrath James White turns his unflinching eye upon the gruesome, the violent, the tragic, and the erotic. Follow a man as he pushes himself through a “body transformation workout” in an attempt to survive a zombie onslaught. Read a poetic account of junkies addicted to a drug that rots their flesh who battle each other arena-style, hoping to survive until the next fix. Consider the consequences of what might happen if the cells you shed in the natural passage of time came back to haunt you. Ponder a new drug that creates radical highs and even more radical aggression—and much, much more.

Rabbit Hunt

Six college kids go into the woods to drop acid, eat mushrooms, smoke weed, commune with nature, and have sex. But they aren’t alone. There are others who have come to fill the woods with screams and vent their homicidal anger and perverse desires on whomever they find.

Mooky, Rashad, Steve, and Big Mike haven’t gone hunting together since their college days. Marriage, kids, and careers have kept them busy and left little time for hanging out with the boys. But that all changes this weekend. For the first time in years, the boys are going on a little rabbit hunt, and the woods will echo with screams.

Taking the “redneck psychopaths in the woods” trope and turning it on its head, the heavyweight of hardcore horror brings you a tale of extreme violence as only he can deliver it.

The Interview

1) I discovered you through reading Poisoning Eros and through my interview with Monica J. O’Rourke, but that’s simply because my head was in the sand: you have an amazing publication record, both on your own and in other collaborative work. In fact, you’ve collaborated with many of your fellow masters of hardcore horror, including Edward Lee and J.F. Gonzalez. What draws you to collaboration? How do you feel about your collaborative works versus your solo endeavors?

WJW: I originally began collaborating as a way to give up control. It was more about personal betterment and development than it was about the story. See, I can be a bit of a control freak. I’m a militant individualist. I don’t even like team sports. Collaborating forced me to learn to play well with others.

I can recall when I collaborated with Lee on Teratologist, and some reviews and comments on social media barely mentioned me and kept calling it “Ed Lee’s new book.” Monica asked me if it bothered me, and it really didn’t. I was just happy we had written something I was proud of and got paid for it. It paid off in the long run.

I love the collaborations I have done, but I am understandably proudest of my solo work.

2) In her interview, Monica says we can thank you for the moral dimension of Gloria’s battle through hell in Poisoning Eros. To rephrase an issue I raised with her, I see tension in the book between a repudiation of what Nietzsche would call the “herd morality” that poisons eros and a condemnation of Gloria despite narration from her perspective (like John Milton taking Satan’s perspective to show its flaws in Paradise Lost). What do you think—does this book lean more toward the Nietzschean or the Miltonic? Why? What is the book’s moral vision?

WJW: My idea for the book was to show a true hero’s journey from the very lowest depths, an HIV infected, heroin addicted, former porn star doing donkey shows for drug money who rises to become the ruler of hell. I wanted it to be a critical view of the Christian vision of heaven and hell. In that way, it shares more similarities with Milton than Nietzsche, though I think Nietzsche would have approved.

3) The Ecstasy of Agony expands your work’s moral purview with stories such as “99 Cent.” “First Person Shooter” offers a cutting moral critique of the influence of violent video games like Grand Theft Auto on players, especially young ones. Does this critique of hardcore, violent video games apply to hardcore, violent horror fiction? Why or why not? Many people who condemn violent video games also condemn violent fiction. What would you if say in response if such people attacked your work?

WJW: It isn’t so much a critique of hardcore video games as it is a critique of the hypocrisy behind those who play Grand Theft Auto or Mortal Combat yet would think extreme horror authors are morally bankrupt for what we write. In video games the player is an active participant in the violence. In books the reader has a more voyeuristic role. I don’t think either would drive an otherwise peaceful person to commit murder.

4) Many stories and poems in The Ecstasy of Agony meditate on masculinity. “Seven Years” and “The Devil in the River,” for example, reflect on young Black men growing up in the ghetto, while “Big Game Hunter” and “Horse” take an interest in gay male identities, and “Big Brother” reflects on a racist stereotype about Black men in a way that is… inimitable. To what extent does a desire to represent and reflect upon masculinity inform your creative process? What do you want readers to take away from this strain of social realism’s combination with your trademark extremity?

WJW: I used to have a very “alpha male” view on masculinity. A man’s worth was measured by his ability to protect and provide, how well he fought, and the size of his penis. That changed as I grew up. Leaving Philadelphia at 19 years old, seeing more of the country, and more of the world, being exposed to different viewpoints, and different lifestyles, challenged those assumptions and prejudices I had been raised with.

So much of what those outdated ideas labeled “masculinity” are merely accidents of birth, even including one’s ability to provide for their mates or their family. Does the fact that one person was born into a wealthy family rather than poverty make them more masculine? What about someone having the genes to be a six-foot-five, two-hundred and thirty pound behemoth as a opposed to a slim five-foot-seven? Does that make them more masculine? What if they are born gay or trans? Does being born with sex organs that are above average in length or girth make one more masculine? If you lose your penis are you no longer a man?

The phallus has been almost deified in many cultures, including Black American culture. It’s ridiculous when you think about it. It’s far too arbitrary to be meaningful, yet so many people in our culture still hold those views of masculinity. I wanted to shatter that. In “Big Game Hunter” I show how many gay men, particularly gay Leathermen, can be uber masculine, even more so than heterosexual men. In “Big Brother” I wanted to expose the objectification and fetishization of Black men for their sexuality. All of these traditional measurements of masculinity are extremely toxic and therefore perfect fodder for horror.

5) Your poetry in The Ecstasy of Agony focuses on narrative, deep use of first-person perspective, and careful repetition. How do you determine which stories are poetic and which are pure prose? How do you know when and what to repeat to create the images and rhythms of your poems?

WJW: When I sit down to write a poem that’s the focus. Not just to tell a story, but to write poetry. I look for ideas that would lend themselves to verse, just as I search for ideas that would make good novels. Sometimes a writer might begin writing a short story then realize it would work much better as a novel, and vice versa. That doesn’t really happen with poetry. I have never had a poem become a short story. I would consider that a failure.

Discipline and control are inherent in the medium. The poet has to maintain control over the story so it doesn’t blow up into something that wouldn’t fit into a poetic structure. I do that by choosing each word carefully. The poems are meant to be read aloud, so the word choices, including the repetitive phrases, are dictated by how they sound when spoken and the impact I imagine them having upon the reader or the listener.

6) Some of your stories in The Ecstasy of Agony, such as “Blue and Red” and “Horse,” have sharp political edges. What reactions do you hope to get from the political content, and what reactions do you actually get? Have you had trouble with critics or other readers complaining that hardcore horror and political statements don’t mix?

WJW: I have often said my best stories come from arguments. Something vexes me or rouses my ire, and I put it in a story. With the current political climate being what it is, I think readers expect me to comment on it. I don’t believe every story needs to make some profound sociopolitical statement, but the best stories do, in my opinion. The books that seem to be most popular now are the ones that are pure escapism. Gross for the sake of gross or just a fun violent romp. I enjoy those books, too, but they don’t really leave an impression upon me. I want my books to stay on the reader’s mind and give them something to think about, perhaps cause them to rethink their opinions. Whenever I hear from a reader who says something I wrote made them change their view on a subject, I am overjoyed. Unfortunately, it doesn’t happen as often as I would like.

7) The beginning of your description for Rabbit Hunt, about a group of college kids heading to the woods to do drugs and have sex, sounds a bit like the setup for a slasher story, in which such kids would typically be butchered in nasty ways as (usually implied) punishment for the drugs and sex. What, if any, sympathy does Rabbit Hunt have for this group of kids? Do their fates involve a moral commentary on their illicit behavior? Why or why not?

WJW: There is an underlying moral message, or perhaps a sociopolitical one, but it has nothing to do with drugs or sex. Rabbit Hunt takes a look at racism from a more humorous viewpoint. In the past, when I have tackled such subjects, I have done so very seriously. 400 Days of Oppression is a good example of that. Aside from the sex, it’s almost joyless. This time I wanted it to be more like a very brutal, very gory skit from the Chappelle show. I wanted it to be so over the top the reader can’t help but laugh even as they wince and groan. If you can imagine what it would be like if Dave Chappelle wrote an extreme horror novel, you’d probably get something like Rabbit Hunt.

8) The description of Rabbit Hunt also promises that the story turns the trope of “redneck psychopaths in the woods” on its head. Minimizing spoilers, could you share a little about what you do with this trope and how Rabbit Hunt challenges expectations?

WJW: Well, first the antagonists aren’t inbred rednecks. They are from the city and just travel to the forest to wreak havoc. Other than that, I can’t really say much without giving it all away.

9) Of course, readers will expect “extreme violence” from Rabbit Hunt. Again, minimizing spoilers, could you share some tastes of the horrific images and events that you have in store? In addition to these horrors, have you also built in some of the social commentary that runs throughout The Ecstasy of Agony? If so, what social issues do you target?

WJW: There’s a scene involving tree branches that would satiate the hunger of the most jaded gorehound. There’s also a juicy scene that involves a cheese grater and an apple corer. There’s torture, dismemberment, cannibalism. It’s pretty extreme. This is one of the few books I would be comfortable identifying as “Splatterpunk” in the historical sense. And, as I said, there’s a lot of commentary on racism.

10) Your works Pure Hate and Everyone Dies Famous in a Small Town were recently rereleased by Madness Heart Press. What insights might draw readers to these newly-available works?

WJW: I actually made a post on my Substack page about the events in my personal life that influenced Pure Hate: https://wrathjwhorror.substack.com/p/the-story-behind-pure-hate It’s an ultimate revenge tale.

Everyone Dies Famous In A Small Town is as close as I can get to quiet or cozy horror. It has some graphic sexual scenes, but there’s minimal gore. It’s sort of a ghost story involving Native American folklore.

About the Author

Wrath James White is a former World Class Heavyweight Kickboxer, a professional Kickboxing and Mixed Martial Arts trainer, distance runner, performance artist, and former street brawler, who is now known for creating some of the most disturbing works of fiction in print.

Wrath is the author of such extreme horror classics as The Resurrectionist (now a major motion picture titled Come Back to Me), Succulent Prey and its sequel Prey Drive, Yaccub’s Curse, 400 Days of Oppression, Sacrifice, Voracious, To the Death, The Reaper, Skinzz, Everyone Dies Famous in a Small Town, The Book of a Thousand Sins, His Pain, Population Zero, If You Died Tomorrow I Would Eat Your Corpse, Hardcore Kelli, and many others. He is the co-author of Teratologist co-written with the king of extreme horror Edward Lee, Something Terrible co-written with his son Sultan Z. White, Orgy of Souls co-written with Maurice Broaddus, Hero and The Killings both co-written with J.F. Gonzalez, Poisoning Eros co-written with Monica J. O’Rourke, Master of Pain co-written with Kristopher Rufty, and Boy’s Night co-written with Matt Shaw among others.

Wrath lives and works in Austin, TX.

Andrew’s Reviews

Poisoning Eros, with Monica J. O’Rourke (2016 edition)

When my brain tries to process Poisoning Eros, a literary onslaught of sexual violation and myriad other forms of visceral violence, it retreats into classics. For its interest in the miseries of Inferno, I go to Dante, and I find a similar urge to map and describe a great variety of tortures. For its underlying morality play infused with Nietzschean insight—which I discuss with both White and O’Rourke in our interviews—I go to Milton. For the admittedly somewhat repetitive scenes of rape and flesh torn asunder, I go to the Marquis de Sade. Poisoning Eros’s effectiveness comes from being like all of these and none. Dante’s perspective character, Dante, is a tourist in Hell. In Poisoning Eros, Gloria, the central character, similarly explores Hell but is a participant in its horrors in ways that range from passive to very active. Gloria faces moral questions that will be familiar to readers of Paradise Lost, but such readers will likely notice the questions’ distinctly contemporary edge, and they’ll also notice that Milton never asks questions about whether fucking a giraffe is the right thing to do. As for the Marquis de Sade, he lies behind many an extreme horror tale. Interestingly, Gloria has a bit in common with both Sade’s Justine and Sade’s Juliette, both ultimate victim and ultimate libertine, and though her journey isn’t directly comparable to either of Sade’s characters’, it has shades of both. All these comparisons are more than an exercise. You could read Poisoning Eros as merely a bare-bones narrative about a drug-addled porno actress who gets dragged to hell along with her daughter and tries to save the girl and escape—a bare-bones narrative that allows for an almost ceaseless gorefest—but you’d miss quite a lot. Poisoning Eros is an almost ceaseless gorefest, but it is as intellectually rewarding as it is viscerally unsettling.

The Ecstasy of Agony (2023 edition)

Wrath James White is a master storyteller and pulse-pounding poet, and he plays both roles in The Ecstasy of Agony, a collection of horrific short stories and poems, all seventeen of which tend to be as artful and hardcore as his longer prose works. With, and sometimes through, the violence, White offers social and political insights that deepen his fictional worlds, the characters, and sometimes even the suspense. Larger interests include varied perspectives on masculinity, addiction, racism, and particularly the intersection of race and economics, but each story or poem brings something special to the fore. The opening story, “Beast Mode,” considers the limits of the human body as a source of hope in what might be a hopeless situation (maybe life itself?). “First Person Shooter” offers a parallel—that becomes an intersection—between street violence and video game violence. Two of my favorites, the poem “Krokodil” and the story “Seven Years,” rely on a bit of science fiction. “Seven Years” follows several narrative strands; the idea that humans replace virtually all our cells every seven years brings those strands together. “Krokodil” describes arena-style combat among addicts to a drug that makes their flesh rot while they’re still alive. White’s verse is rhythmic, and he knows how to repeat phrases for impact. For example, in another poem, “Screams in Bobby’s Eyes,” repetitions of “When the hammer struck” and “When the screwdriver pierced” quite vividly drive points home. This collection is grim, but it doesn’t lack humor. “Big Game Hunter,” a story about a gay man who hunts other gay men, takes a surprising turn that made me snicker. The final story, “Big Brother,” gruesomely, uh, skewers a racist stereotype, and I couldn’t stop smiling. Overall, the book is diverse, thoughtful, hardcore fun, highly recommended as an introduction to White’s gruesome and horrific ways (as it was for me) or as an expansion of your Wrath James White library.

Pure Hate (2023 edition)

Pure Hate is a story of revenge and obsession taken to (almost) unthinkable extremes, a fast-paced, suspenseful tale with cat-and-mouse dynamics that shift among the police, a serial killer, and the serial killer’s primary targets as horrifically mangled bodies pile up around the city of Philadelphia. Roughly the first half plays like a thriller—or would if White didn’t decorate it with his trademark hardcore violence, truly exquisite gruesomeness that enhances the experience and pushes it over the line into horror. Nevertheless, I felt at times like I was reading a really, really good episode of Criminal Minds, following one street-smart and one book-smart cop as they try to figure out a serial killer who defies familiar patterns. White isn’t content to let his book work in only one mode, however, and shifts midway toward an emphasis on the perspectives of the killer and the object(s) of his obsession, making the horror more intimate and scarier. His characters are deeply flawed but still relatable, even the killer (for one reason why, be sure the follow the link in question ten of the interview above). I found the book difficult to stop reading, so I didn’t do much reflection along the way, but afterward I felt like I had just read one of the most insightful literary studies of masculinity that I’ve encountered since I last read Ernest Hemingway in my early 20s. White has much to say about power differentials between men and women (a lot of it disturbing), but he excels at depicting investments in body image, anxieties about social standing, struggles for interpersonal control, uncertainties about emotional expression and repression, and many other issues associated with “being a man.” Such issues aren’t tangential or add-ons: they ultimately lie at the heart of the story, propelling the killer and his obsession. Behind Pure Hate’s passion is an analytical mind that delivers a layered experience, a read that’s fun and liable to stay with you.

The Resurrectionist (2014 edition)

Probably White’s calling-card novel at this point, The Resurrectionist grows from a deceptively simple, speculative premise, indicated by its title. What if a young man had the power to bring people back to life? What if, instead of being someone who would use such power for good, that young man were a sexual sadist who uses the power to torture, rape, murder, and then resurrect women so he can repeat his pleasures night after night? White adds to the mix that the people his Resurrectionist, Dale, brings back don’t remember the horrific things that have happened to them, introduces the character, switches to the perspective of one of his female victims, Sarah, and lets the story unwind its horrors. The first half, mostly from Sarah’s perspective, plays with the nerve-racking tension of a classic Gothic novel: the female protagonist knows things are happening to her, knows she is in grave danger, but no one (except the reader, of course) believes her, so she feels increasingly helpless and trapped. Like in Pure Hate, however, White doesn’t let his novel linger in that mode, as eventually Sarah gains credibility, and the conflict broadens along with the number of brutally mutilated—then resurrected—victims. Sarah, her husband Josh, and Dale are well-developed characters, Sarah smart and sympathetic, Josh conflicted and haunted, Dale psychologically accessible, at least to a point, but terrifying in being so. The book, which features a lot of graphic rape, is also surprisingly thoughtful about rape, self-conscious and inclusive of multiple perspectives (none but the killer’s approving, of course). An unexpected layer of insight also comes from the setting in Las Vegas after the post-2008 economic downturn. Abandoned houses and the unavailability of jobs become plot points as well as reminders of poverty’s far-reaching impact. The Resurrectionist is exceptionally well-crafted, a very rewarding read that is rightfully already a classic of hardcore horror and deserves to be counted among the more general horror classics of the early twenty-first century.

NOTE: The Resurrectionist has been adapted into a film, Come Back to Me (2014). I don’t generally require adaptations and remakes to be “faithful” to their precursors; films must reflect their medium and historical contexts. By industry standards, White’s novel’s extremity is unfilmable and had to be changed; I can accept that. However, this film’s withholding of the information indicated by White’s title as a sort of twist later in the film doesn’t really work, and failure to develop Josh’s character or the police characters (the latter of which might have been a budgetary decision) makes the film feel two-dimensional. In short, I can’t really recommend it, but it’s not terrible, so if you’re curious after you read the book, why not?