Multitalented filmmaker Michelle Iannantuono talks about her feature horror films Livescream and Livescreamers, which combine cinema and gaming in innovative ways for unusual and exciting scares.

Livescream

Every day, over 200 loving fans watch Scott Atkinson play horror games online. After a lifetime of failures and false starts, streaming games is the only thing he’s good at. It’s the thing he loves the most. Until it becomes a nightmare. Enter Livescream—a mysterious horror game sent to him by an anonymous fan. At first, he thinks the game is a low-quality indie title. But when his followers start dying one by one, he soon realizes the game is far more sinister. Now, Scott will be forced through nine levels of video game hell, each level representing a different horror game niche, in order to walk away alive. It might just cost him his fans, and his soul, in the process.

Livescreamers

In this sequel to 2020’s Livescream, a popular group of content creators face the ultimate lesson in teamwork when a haunted video game begins killing them one by one.

The Interview

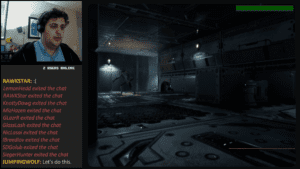

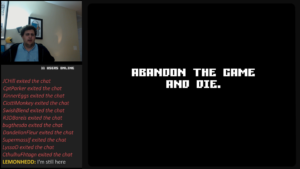

1. Streamscreen. Livescream mimics a streaming experience, splitting the screen into areas where the audience can see Scott, the game player who talks to his stream’s viewers, in the upper-left corner, his viewers’ text-based commentary in the lower-left corner, and the game Scott is playing on the right. The story unfolds in all three areas and through their interactions. While the form makes sense for the content, the split-screen approach is unusual and got me thinking about films as different as Carrie (1976) and Timecode (2000). What inspired your approach? It seems risky because it demands more from the audience—how does the film manage the audience’s cognitive workload? How do you think managing information from three sources (in three media: video, text, and digital animation) affects the viewers’ responses in terms of fear and horror? How do you think the film’s form plays post-COVID, a time when, thanks to the rise of platforms like Zoom, people are more accustomed to split-screen/multimedia communication interfaces?

MI: It was really important to be aware of “eye tracking” during the editing of Livescream, which is a technique best demonstrated in movies like Mad Max Fury Road. There are a lot of cool video essays and literature about this, but essentially, you want to anticipate where you are pulling the audience’s eye from moment to moment and ensure there is good flow.

Plus, even though the story is divided between chat, gameplay, and Scott, there is only ever one essential thing happening on screen at any given time. In terms of managing horror, it is a way to pull some visual sleight of hand. For instance, most people cite that they never realize Scott gets up and leaves frame, because they’re too busy watching all the viewers leave the chat in that moment. It’s a bit easier to pull off scares in the game when they happen immediately after distracting the audience with the chat.

Finally, it is interesting to think about the impacts of COVID on screenlife, good and bad. On one hand, I feel like the market has been deluged with “in screen” movies, and I have faced some hurdles in marketing the sequel, Livescreamers, post-COVID. I get a lot of comments that no one wants another “Zoom Movie” even though both films are massively more ambitious and stylized than a simple video chat. However, having other comp titles is a bit of a strength. Back during 2018, I had few movies to really compare Livescream to, which made it hard to describe to people.

2. Longstream. Speaking of Livescream’s experimental form, Scott’s video portion of the narrative (with a brief exception) takes place in real time in his corner of the screen as if it were from an uninterrupted run of a webcam. In other words, as a movie unto itself, Scott’s portion might join the “single take” horror/thriller tradition, the most famous member of which is Hitchcock’s Rope (1948), a more recent example of which is Silent House (2011). Both of those movies faked it. Is Scott’s portion an uninterrupted, single take? If so, why was getting that take important enough to go to the trouble, and how much trouble was it? If not, why was the effect important enough to simulate, and how did you pull it off?

MI: It is faked by stitching three takes (again, stitched the two times he exits frame and comes back), although the middle take was a long, uninterrupted 35 minutes. I think this was really important to simulate because we’re supposed to be doing a livestream on Twitch. Those would be uninterrupted and done in real time, inherently.

3. Streaming Countdown. Another horror tradition in which you could position Livescream is the body count film, the slasher or mutations of the slasher such as Saw (2004) that, like Livescream, have victims “dying one by one.” In what ways do and don’t you see Livescream using, and perhaps playing with, slasher conventions? Which do you think are scarier, the glimpses of violence we catch onscreen or the moments of violence we catch by implication? Why?

MI: It is nice to see it recognized as a slasher, as a lot of people miss that. It gets classified more often as tech horror, found footage, screenlife, etc, but at its core, it is a slasher. Scream is one of my favorite horror films, and I always borrow a lot from that movie’s plot progression. You have to cross into Act 2 with a body that the main characters know about. You have to have a consistently dwindling cast, although you also have to have some moments where your characters eke out of a set piece alive – otherwise every set piece becomes a repetitive and suspenseless endeavor where you know they’re doomed.

The limited onscreen violence is mostly a result of budget and format – you just don’t really see your followers’ faces, as a content creator – but I think it worked out for the best. Scott has a moment at the end where he finally sees the faces of the folks he lost, including someone who was a dear friend, and that’s pretty emotionally impactful, I think. Wouldn’t have been the same had you seen the blood spray earlier or known what these guys had looked like. I had to kill one of them on screen in order to sell the idea that the game was actually killing people, but beyond that, the film is deliberately vague.

I’ve lost a lot of internet friends over the years who just kind of vanished from social media or LiveJournal or whatever out of the blue, and I still to this day wonder what happened to them. There is definitely something haunting about not having answers to the fates of your online friends.

4. Screaming Countdown. The diminishing numbers of the living in Livescream are also diminishing numbers of Scott’s followers, and much of the drama and suspense in the film surround Scott’s relationships with those followers, as they are his social lifelines and the keys to the only activity that gives him fulfillment. How does your film reflect on people’s relationships with online personalities and those personalities’ relationships with their followers? How much of the horror comes from the psychological impact of Scott’s crumbling community and the way he diminishes along with his numbers?

MI: Livescream is a rather optimistic look at online community, as I was on the fan side of things at the time. I was inspired by how people found solace and friends within fandoms, rallying around a creator to make connections. Even Scott’s relationship with his mod, JumpingWolf, is an emotional core to reinforce the idea that a follower/creator relationship can be really pure and inspiring, and it doesn’t always have to be a toxic parasocial hellscape.

Part of the horror of losing these followers is because Scott genuinely recognizes and cares about them as people. He is a smaller streamer who is not really depending on this following for income or enterprise. To see them harmed because of his stream is deeply disturbing to him because he has felt like he has a bit of responsibility for his community all this time, creating a safe space for the lonely misfits of the world, and that space becomes immediately unsafe when playing Livescream. Losing this one thing he loves so much is pretty horrific when you realize all this guy wanted was community.

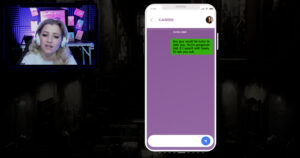

The sequel Livescreamers is a total inversion, showcasing what happens to the relationship between community and creator when it does become a business relationship. When fans equal income, when clout equals better business, and when creators ascend into idols. It was a reflection of my life after years of becoming a creator myself, having my own audience and experiencing invasive dynamics, as well as navigating the waters of asking for money in an ethical way.

5. Streaming Archives. The film we see is (mostly) Scott’s page for streaming his game-playing, which might very well be archived, so it could be an internet artifact we as viewers have stumbled upon—the online equivalent of found footage (if you’ll forgive me—found footage 2.0). In what ways do and don’t you see Livescream using, and perhaps playing with, found footage horror conventions? At least since The Blair Witch Project (1999), found footage films have been tied to internet-supported lore. The seemingly predatory game within Livescream, also called Livescream, may well be the gaming world’s answer to Slenderman. What, if anything, does Livescream have to say about internet artifacts and internet lore?

MI: I always thought it would be fun if MatPat got ahold of the film and broke it down in one of his Game Theory/Film Theory episodes. I suppose that’s really all of it – more than commenting on creepypasta or internet lore directly, the film features some aspects that could have been bait for folks who are into that sort of thing to take and run with. What is the Siren? Why is the game doing this? These are questions that don’t really have good answers – albeit somewhat elucidated in Livescreamers but still not too literally. They’re mostly fun carrots for folks to chew on in a Reddit thread. Borderline ARG, if you will!

For Livescreamers, we also have janusgaming.com which is an “in universe” website for the characters. I post in-character reels on the social media for Janus Gaming too. Just a bit of a fun way to expand the world and let the audience get to know the characters like they’re real humans.

In terms of found footage conventions, I don’t think I borrowed much. For a long time, people thought it had to be Cloverfield or Blair Witch adjacent to be found footage – shaky cam, shot on tape, narrator cameraman. Screenlife was a bit burgeoning in 2018, although The Collingswood Story and Unfriended had broken ground. But in a lot of ways, Livescream and Livescreamers do a lot of new things that no one else has (or had). Livescream is one of the first movies – I think – to incorporate some sort of “chat” element, which is now pretty popular with movies like Spree, Deadstream, Chad Gets the Axe. There aren’t many found footage films that incorporate gaming, sans Deadware. But what all these movies have in common is immense creativity, and that’s really the heart of the genre. If there’s a convention I love about found footage, it’s the constant opportunity to do something innovative.

6. Indie Scream. The game within the film goes through different phases and styles of varying graphical quality. At one point Scott comments on graphics getting an “upgrade,” but he refers to the graphics in general as being “indie,” meaning low-quality. To me, they look like older—let’s say “vintage”—game graphics, and they go well with music (both diegetic and extra-diegetic) with a vintage edge. Why does the game go through different vintage styles, and why did you choose (if you agree with my characterization) a vintage aesthetic? Do you think there’s something scarier about a less sophisticated gaming interface? Why or why not?

MI: Well, that’s low budget for you (lol). I made all the games myself with no experience and with purchased assets. Much like how the webcam format masks the fact that I’m a weak cinematographer, doing it in an indie game aesthetic masked the fact that I was a weak game designer.

But also, most of the games homaged were of similar simplicity and low resolution. There’s a reason I saved Resident Evil for the sequel, and focused on stuff like Slender The Eight Pages, or Five Nights At Freddys for the first Livescream. That being said, I just announced that Livescream is getting a rebuilt remaster later this year, with better looking game design, a 4K and 5.1 mix overhaul, and new graphical design throughout. And it will be an interesting needle to thread, to preserve the “indie” origins of some of the games homaged, while also making the games have far greater visual finesse. I’m already predicting some backlash, funny enough, because some people really dig the lo-fi gutter aesthetic of Livescream’s games! I guess some people do think there’s something creepier about it, even more than the much more polished House of Souls game that the characters play in Livescreamers.

7. Living Hell. The description of Livescream that I cribbed from IMDb describes Scott going through “nine levels of video game hell,” suggesting an extended Dante reference as well as a potential moral dimension, which might become stronger toward the end as continuing to play becomes a deeper and deeper moral quandary. Does Scott go through hell due to some sin or moral imperfection? Does the game Livescream—and/or your film Livescream—have a moral message or mission? If so, what can you say about it without giving too much away? If not, what’s the significance of morality’s absence in a video game hell?

MI: I have always been drawn to Dante’s Inferno – it creeps up in a lot of my work, including stuff that never saw the light of day. Maybe there’s just something sublime about the number 9, as Livescreamers also features nine characters.

But I don’t really think I present the idea that hell = a morally motivated punishment ever. More often I present the idea that hell = any punishment at all, very often unjust or undeserved. Every character I’ve ever put through a sort of hell didn’t really deserve it but was actually oppressed in some way. Leave it to the queer person with no religious background to basically say, “this shit is made up and hell is not fair.”

8. Live Upgrade. With only Scott on the screen for any extended length of time, Livescream feels very intimate despite the reach of its horrors. Livescreamers focuses on a multiplayer gaming experience, leaving out the viewer commentary and instead focusing on a group that inhabits the same physical and digital spaces. What new opportunities for character-driven horror alongside conceptual and visceral scares does this shift in focus open? The graphics are much better—do you feel there’s more of a focus on the digital components? Yes or no, what difference do you think the graphical upgrade makes to your storytelling?

MI: Gunner Willis was a powerhouse solo performance in Livescream, and it also utilized some of my novel writing chops to inspire the audience to connect with characters whom you only ever meet in text. But with only a couple main characters at the core of the story, the emotional arcs are pretty simple. A lot of the entertainment of the film then becomes about “spot the homage!”

Even though Livescreamers is a visual facelift, I actually think the game is less of a focus. The first Livescream is very much a love letter to existing horror games. The chat is drowning in easter eggs. We trade a lot of that winking and homaging in Livescreamers for character and drama instead. The games are set pieces filled with tension, but that tension often comes from shining a light on the flaws of the characters or on good old-fashioned scares. Sure, Livescreamers has its share of borrowed mechanics and familiar aesthetics, but it’s not nearly as much of a fandom parade.

As for multi-player, it was a huge opportunity to work with an ensemble of on-screen actors who you can see, you can hear, and who you can actually see die. I’m really proud of my cast for bringing nine very different humans to life, all of whom represent some form of monster that has been created by the gaming and streaming industry. And hey, it’s less reading for the audience, which I think a lot of folks appreciate.

9. Livescream and Livescream Again! Horror sequels generally up the ante for onscreen action and violence as well as, when mystery with potential for deepening lore is involved, greater development of mystery and lore. At one point a character in Livescreamers refers to ongoing events as “al dente creepypasta.” What are the sequel’s attitudes and—vaguely, without spoilers—contributions to the larger lore of the game and its imperiled players? What can viewers expect in terms of upgrades to the horror’s visibility onscreen?

MI: In terms of upgrades, it is hella gorier and more violent than the first one, including emotional violence. While Livescream touched on the horrors of depression, loneliness, and those who seek purpose in a punishing world, Livescreamers goes even deeper in real world horror, touching on sexual harassment, corporate greed, racism, queerphobia, PTSD, and more.

The larger lore wasn’t really going to be explored, because I just hate when tech horror tries to explain itself too hard. Just slows down the whole movie and ruins disbelief when you have some crone whip out an old Bible and say, “the demon Azazel is now targeting cell phones!” or some shit. I actually was told in an early development note to explain the motive of the game more, and while I took that note a bit to expand upon the rules and motives of “the House” and “the Siren,” I refuse to give any sort of explanation as to where this all began and where it came from. I cannot think of an answer that doesn’t amount of “midichlorians.”

Because ultimately, a rigged game that forces characters against each other is just an allegory for capitalism. Even if you “win” the game, there will be consequences waiting just outside the door – a bigger game you cannot win, no matter how ruthless you are to your equals in the gutter. Scott is an example of someone who is trapped in such a game and can’t really win as a solo person, even with best intentions. The characters of Livescreamers show that if you abandon your peers, you’re similarly doomed. The only real way out is teamwork.

10. Access! How can people learn more about you, view your films, purchase your films, and generally get access to your world (please provide any links you want to share)?

MI: Big things coming to the Octopunk Media channel on YouTube this year (http://youtube.com/octopunkmedia), including the worldwide FREE premiere of Livescream on Saturday 2/10! I am also on Instagram @octopunkmedia, and if you’d like to join our community, you can check out our Discord server https://discordapp.com/invite/evxxwef

About the Filmmaker

Michelle Iannantuono is an award-winning writer/director from Charleston, South Carolina. Her previous features include 2018’s Livescream, which was nominated for a Rondo Award and won Best Director at Nightmares Film Festival; 2020’s Detroit Evolution, a queer transformative fan film in the Detroit Become Human video game universe that has surpassed 2 million views on YouTube; and 2023’s Livescreamers, recipient of Best Screenplay at Genreblast and Best Director at NYC Horror Film Festival.

Her previous shorts include “Fame Fatale,” “Seven Deadly Synths,”, and “Detroit Reawakening,” which has half a million views on YouTube. She also produced Michael Smallwood’s “What a Beautiful Wedding,” which screened at FilmQuest, NYC Horror Film Fest, and more.

She is at the helm of Octopunk Media, a media production company with over $25,000 raised for charity to date, a combined 70,000+ worldwide followers, 150+ paying monthly patrons on Patreon, and with fan events hosted in NYC, Munich, Detroit, and London.