Interview with Author David-Jack Fletcher: Raven’s Creek and The Count (2024)

Bestselling, award-winning, and (most importantly) scary and super-fun author David-Jack Fletcher discusses his novel of science run amok, Raven’s Creek, as well as his recently released shocker, The Count.

Raven’s Creek

2023 Bookstagram Winner for LGBTQ+ Novel of the Year

An abandoned motel.

A woman flees an unknown danger, taking refuge in a motel. She is never seen again.

A mad scientist.

A geneticist stretches the boundaries of nature. His experiments, once human, are now something else. Something new. Something hungry.

The couple.

Michael and his husband Geoff have lost something precious. Their search takes them to a motel. What they find there will reveal a cruelty neither knew existed. And creatures beyond imagination.

Welcome to Raven’s Creek.

The Count

When Sam’s ex, Danny, winds up gutted beyond recognition, Sam has no memory of where he was at the time. He can only remember the strange comfort of his new house. The endless ticking of a clock he can’t find. The bloody knife he woke up holding the morning Danny was killed.

Sam’s guilt over Danny is undercut by the endless ticking, a growing desire to drink from the dead, and anonymous GPS pings that lead him to corpses. The stench of them rotting makes him hungry.

He begins to feel the ticking inside him, feeding a darkness he’s long ignored. It compels him to take what he wants, regardless of the price. When he begins to act on his bloodlust, the ticking leads him to the death of a loved one.

The clock begins to point to more of Sam’s friends and family, begging for their blood. Fueled by a deep desire to feed, and compelled by the power of the ticking clock, how far will Sam go to get what he wants?

The Interview

1. Gay Plots 1: Surrogacy. To discuss too much of Raven’s Creek’s storyline would give away some of the delightful twists that keep coming throughout the novel, but we learn early on that Michael and Geoff are using a surrogate mother to have a child. This aspect of the story seems at once especially gay—if two men want a baby using some of their own genetic material, surrogacy is a prime method—and also sort of heteronormative, as it makes reproduction and saving a child seem like primary narrative values. At least early on in the story, do you see the involvement of a surrogate as increasing the queer quotient, or do you think it brings the story closer to classic tales of men saving women and children in distress? What are the consequences of taking either of those perspectives?

D-JF: Wow, this is an incredible question!! For me, surrogacy was an important part of the narrative, because it draws attention to the very real scenario a lot of gay male couples face today. I’ve known people who are rejected for surrogacy because they are gay, and this has serious implications for how some of these organisations view ‘family’.

To answer your question, though, I don’t see Geoff and Michael as driven by a need to save the women and children in distress; it’s more about their unquenchable desire for a family. They have a bond with Adelaide, as well, who very much takes a heroine role throughout the story.

I think you raise a really interesting point, though, about the parallels in Raven’s Creek with man = hero, woman = victim. I tried to minimize that, because there are a few very powerful women in the novel (without spoilers!). It is something I try to be mindful of in my writing, because I don’t want to reproduce heteronormative stereotypes; I want to highlight and explore queerness.

2. Acceptance, West Virginia. If I understood the navigational details correctly, Raven’s Creek is a backwater in West Virginia, USA, the kind of place where at least my husband and I wouldn’t expect to be universally welcomed. Nevertheless, though Michael and Geoff face all kinds of trouble, homophobia isn’t really one of them. Is your depiction of acceptance one of the fiction’s fantasies or a reflection of how far you think the culture has come? How did you reach that point of view? Do you think the story would work as well if more characters reviled Michael and Geoff for being a same-sex couple? Why or why not?

D-JF: Oh no, not at all. I think we all face homophobia, and culture has not come very far at all. Literally yesterday on the news there was a petition about banning a same-sex parenting book from libraries. We are definitely not ‘there’ yet with acceptance. I tend not to focus too much on homophobia in my work because I want to be beyond that point, and in order to get there, in my view, presenting gay and queer couples / people as simply here, existing, and doing what we do, is a critical step.

3. Science and Ethics. Raven’s Creek comments directly on the consequences of scientific research unrestricted by ethical boundaries, and it uses sci-fi/horror classics such as H.G. Wells’s The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896) and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), as well as Frankenstein’s film adaptations (especially James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein, 1935) as touchstones while getting into much more contemporary issues such as genetic manipulation and nanotechnology. One character even has a god complex arguably bigger than Dr. Frankenstein’s. Why do you evoke these touchstones? Do you see yourself carrying on their cautionary traditions? Why or why not? Do you think contemporary scientific research overreaches ethical boundaries? Why or why not?

D-JF: Raven’s Creek is about morality and what it means to be ‘human’. One of the creatures in the book is arguably more human than anyone else, just like our old pal Frankenstein’s monster. I have an interest, generally, in what makes us human, and how people justify cruelty at the expense of compassion and morality. Is it okay to experiment on people if they are in the lower socio-economic classes, as has been done historically, and how can we possibly justify that?

Our mad scientist in Raven’s Creek is driven by power, despite his initial good intentions, and I see his character as a representation of what can happen when we put the ends before the means. I don’t see myself as carrying on any traditions per se, but I definitely think there are unethical practices in several scientific processes these days. I did a lot of research on anti-aging for my PhD, and while the research might be useful, it can often be done in questionable ways.

4. The Filthy Rich. Speaking of ethical boundaries, some of the transgressions in Raven’s Creek are enabled by people whom one character rightly calls “the filthy rich,” people who funnel huge sums of money into making bad things happen for their own gratification. Sometimes Raven’s Creek is, um, a little tongue in cheek… does the book level a sincere critique at the excesses of the wealthy? Given the opportunity, do you think a significant number of rich people would do the sorts of things (no spoilers!) they do in your fictional world? Why or why not?

D-JF: I like to think the filthy rich wouldn’t do these things, but that part of the novel was heavily inspired by The Purge 2. I do think the filthy rich are often above the law, which is really what is being commented on there—they are untouchable, or seemingly so, because their wealth makes them too powerful. Adelaide’s ‘rich old man’ is based on a certain Weinstein we know, which I think really sums up how I feel about the potential for evil among the rich.

5. “He wasn’t in a bad movie, despite all appearances.” Raven’s Creek is not without a good supply of cameras and other means of spectatorship, and watching recorded moments factors significantly into the plot. What is your book saying about the desire to look and the effects of being looked at? Characters are sometimes aware of their movie-like conditions. Is this awareness postmodern reflexivity (à la Scream), or does it do something else/more in the story? Do you think that almost anyone who found themselves in situations as bizarre and frightening as those in Raven’s Creek would compare their experiences to movies? Why or why not?

D-JF: To answer the last question first, I know I do this a lot. I’ve seen some car crashes and often compare them to the freeway scene in Final Destination 2. I genuinely do this a lot, so I feel like it’s in the realm of possibility. If my life were in danger, I probably wouldn’t sit there and think, ‘Hmmm, this reminds me of that movie’ , but certainly in hindsight if I were to survive (which I probably wouldn’t).

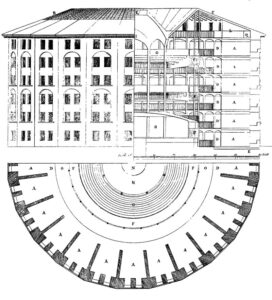

The book, in general, is about morality, as I say, and a key question I have is, what do we do when the cameras turn off? What are our guiding principles when we know we’re not being watched? Do we maintain our sense of morals and ethics, or are they predicated on being disciplined if caught? It’s very much a panopticon situation there.

6. Gay Plots 2: Blood-drinking. Vampires in modern fiction have always been a bit queer, from John Polidori’s Lord Ruthven (“The Vampyre,” 1819) to J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872) to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897: you can’t convince me Drac’s relationship with Jonathan Harker isn’t erotic). The Count isn’t a typical vampire tale, but it deals with the vampiric: do you see yourself building on this queer vampire tradition? If so, what can you reveal about the new twists you’re giving it? If not, where are you coming from with your story about a man who wants to drink from the dead and gets hungry when he smells rot?

D-JF: In a way, I really did see myself as building on the queer vampire tradition. I know that sounds a bit obnoxious—who am I to do that, really? I’ll be honest, I don’t really like what vampires have become in modern fiction. True Blood, Twilight… no. Sorry. I wanted to explore the themes I see as crucial to vampirism without actually having a vampire. So, bloodlust was important for me, as well as the idea of possible immortality at an incredibly high personal cost. Probably the biggest vampiric theme I see, without the drinking of blood, is giving ourselves to a power we can’t fathom, without really understanding why we’re doing it, except perhaps from fear.

For me, I think the twist I give to vampire traditions is that there is no vampire in a physical sense: it’s a presence that anyone really can fall susceptible to.

7. The House and the Ticking. People often say that horror featuring a house important to the plot makes that house into a character. Is Sam’s new house a character? If so, how would you describe its personality? If not, what is it—what function does it serve? The ticking seems to go hand-in-hand with the house, and it also seems to have a tell-tale heart quality. Without giving away too much, how does the ticking operate in the story: supernatural phenomenon, psychological phenomenon, countdown, metaphor, all of these, none of these?

D-JF: The house is definitely a character. It is characterized purely by its desire to feed. It has no morals, it has no qualms about forcing people into servitude, and it somehow outsmarts everyone without necessarily being conscious.

The ticking works on multiple levels, as does the book title itself. It’s psychological because Sam feels connected to the sound, it’s supernatural because he eventually finds a clock, and it also serves a very real function—it tells him when someone is going to die. The fact that the ticking becomes part of him is kind of metaphoric in that he becomes the body the house needs in order to feed. I’m not sure that makes sense, but it makes sense to me.

8. End of the Line. The description of The Count reveals that the ticking leads Sam to the death of a loved one. Another tidbit from vampire lore (the “real” stuff) is that vampires tend to return from the dead and hunt their own friends and families. Are you playing with this aspect of blood-drinking lore? Of course, gay people are supposed to be anti-family because gay sex isn’t reproductive… are you playing with this aspect of homophobic lore? What’s the significance of Sam facing the deaths of people close to him?

D-JF: You’ve really hit on a few different interpretations there, and I’d love to say I’m making a really powerful comment on that one. However, for me, this book is grief horror. Sam has just been dumped by the person he thought was his ‘one’. His grief has overtaken him, and the implication that he’s powerless to stop the deaths of his loved ones is a crucial tension throughout the novel.

9. Sympathy for the Afflicted? The growing numbers of glowing reviews for The Count praise your characters and insist that Sam is sympathetic despite his questionable moral path. What makes Sam sympathetic? Other than a guy who might have killed his ex and who has a hunger for corpse juice, what kind of person is he? Why will readers cheer and fear for him?

D-JF: I’ve been really surprised about the response to Sam. I had a friend message me in the middle of night to say how devastating the ending was. He is a complex guy, despite his downward moral path. For me, he’s sympathetic, because he often questions what he is doing, but seems powerless to stop what’s happening. The ending, too… I can’t spoil it here, but to me, the ending made him sympathetic because of his platonic love for Patrick.

Sam isn’t someone I see as being particularly fearful, but more someone to pity because he is a good guy who is enveloped, and ultimately blinded, by his grief and fear.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

D-JF: Author website: https://www.fletcherhorror.com

Slashic Horror website, where all our titles are available: https://www.slashichorrorpress.com

FB: https://www.facebook.com/davidjack.fletcher OR https://www.facebook.com/fletcherhorror

IG: https://www.instagram.com/fletcherhorror

Twitter: https://twitter.com/fletcherhorror

I’m always keen to connect with readers and authors, so feel free to reach out at any time.

About the Author

David-Jack Fletcher is an award-winning Australian author, specializing in LGBTQI+ horror fiction. He dabbles in comedy-horror and dark fiction, but his true love is body horror.

His debut novella, The Haunting of Harry Peck, is a 2022 Amazon international best-seller across several lists including Gay Fiction, Horror, and Two-Hour Literature. Raven’s Creek (2023) won the Bookstagram Award for LGBTQ+ Novel of the Year and is also a best-seller.

He has also appeared in several anthologies across the US, Canada, and the UK. David-Jack’s newest novel, The Count, was released in 2024. It involves psychological body horror, focusing on bloodlust and the looming certainty of death.

He is also a qualified editor, operating a small online business, Chainsaw Editing, where he specializes in copyediting and developmental editing for horror/thriller, dark fiction, mystery/suspense, and the occasional historical romance. More recently, David-Jack co-founded Slashic Horror Press, which focuses on queer horror.

When not writing and editing, David-Jack can be found on the couch with a book, cuddling his dogs and his husband.