Interview with Author Charlotte Platt: Treasured Guest (2025)

With alluring insights into its layered terrors, Charlotte Platt takes us on a tour of the haunted hotel in her novella Treasured Guest.

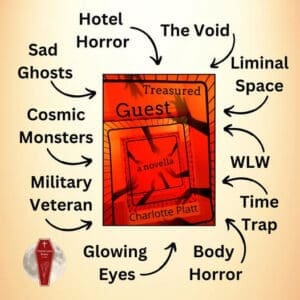

Treasured Guest

The Basker’s delighted to have you.

“Just one drink” the night before has left soldier-turned-corporate-trainer Stephanie with a hangover that could wake the dead. The dead, however, are never restful, and when checking out of her Glasgow hotel goes eerily sideways, Stephanie comes face to face with the very best–and worst–The Basker has to offer.

In fact, the chipper concierge insists she take advantage of his hospitality, leaving Stephanie in an executive suite with every amenity available at the press of a button. Every amenity, that is, except her freedom.

The Hotel Basker and its staff claim Stephanie is their most treasured guest, but she only wants to get home to her partner Jenny and their cats, fighting tooth and nail to find a way out of those rooms and away from the horrors they hold.

Who will prove stronger: The Basker, with its timeless sophistication and uncanny architecture, its bleeding ghosts and cosmic monsters–or one haunted woman, fierce with homesickness and relying on the combat training she never forgot?

Check in and find out.

The Interview

1. Ghostly Guesthouses. On their website, Undertaker Books points out that Treasured Guest has “elements of The Shining.” Stephen King’s opus may be the contemporary go-to for hotel haunting, but (allegedly) ghost-infested accommodations have a noble literary tradition. Go back a century from The Shining (1977) and find Wilkie Collins’s The Haunted Hotel (1878); go forward about forty years and find a whole season of popular television, American Horror Story: Hotel (2015 – 2016). These examples alone create a broad spectrum for haunted hotels: where does the Basker fit? Avoiding spoilers, what elements does it, in fact, have in common with King’s Overlook, and how does it differ? King aside, who (or what) were your influences? Like haunted houses, haunted hotels usually have personalities. Does the Basker have a personality? If so, how would you describe it? What’s the Basker’s place in the world?

CP: This is a very fun question – to me, the Basker leans more H. H. Holmes than King, but it’s undeniable there are hints of the Overlook in there, too. I think the Basker shares a malignance with the Overlook, a desire to corrupt, but the Basker is more likely to drive you to despair, rather than getting you to kill everyone else. It’s a patient predator rather than the escalation the Overlook induces.

For influences, the Basker was inspired by a travel hotel I stayed in for my day job, which was not quite as ravenous as the Basker, but it was rather weird! It didn’t help that I mistook the front of the real-life hotel for the neighboring undertakers twice before I found it, but for all the neighbors to have the dead won’t issue a noise complaint, so there’s a logic to it! Writing wise, I think Clive Barker is always going to be someone I reference because I love his work, but the eco and echo horror of Jeff VanderMeer and Premee Mohamed creep in, too.

As for personality, I’m not sure the Basker has one in the way we’d recognize, though it is playful at times. I’d say it’s more like a big cat or a shark, something that’s intelligent but quite separate from how we’d interact with it. The best link the Basker has to humanity is the ghosts that fill it, but they’re progressively less human the longer they stay, too.

2. More than the Weather? Your hero, Stephanie, stays at the Basker on a trip to Glasgow, Scotland. Most of the audience for this interview will be American, like myself, and might share my impression that the weather in Glasgow is often as you depict it—which is to say, dreary. Do you consider your depiction of Glasgow, at least in that regard, to be realistic, or do you magnify the stereotypical dreariness for the sake of the isolating atmosphere around the Basker? What else, if anything, is particularly Glaswegian (or Scottish) about the Basker and its ghosts? Overall, what’s the significance of the broader urban setting?

CP: This question really made me laugh – I love Glasgow to bits. I studied for five years in Glasgow, and it’s one of the friendliest and liveliest cities in Scotland, but goodness me yes it can rain when the weather sets in. But the city is well adjusted to it: in my last year of studies the worst storm we’d had in 10 years at the time, an actual cyclone, was nicknamed “Hurricane Bawbag” (I’ll trust the audience to understand that one), and other than catching flying trampolines, everyone carried on pretty well. As such, while the Basker is certainly soaking up that dreary rain, that’s just November onwards for most of us in Scotland.

In terms of what else is especially Glaswegian, Frankie, our resident bartender, is very Weegie, and she’s a lot of fun because of it. Glasgow also has some fantastic art galleries and museums, which the Basker takes advantage of in a way.

The urban setting is something I love to play around with. The idea that there’s something magical lurking within the scrum of the city is always appealing to me, and the idea of predatory things evolving to hunt in new ways that could slip into the day to day is very fun. How often would you notice someone with too many teeth, or an extra set of footsteps following you in the dark? Would you know the difference between a mugger and a vampire until it was too late, and would that difference matter if you’re bleeding out either way? Having lived both in the city and very rural areas – I grew up on the Orkney Islands – I think the activity of the city always appeals to me because of how isolated you can be while in very busy spaces.

3. The Winter of Mixed Drinks. Stephanie drinks like many of my characters drink! Um, that is to say, a lot. A fear that her drinking might signal alcoholism does arise once, but otherwise, that doesn’t seem to be an issue for her. Does the novella imply any criticism of her heavy drinking? Why or why not? As hotel ghosts (“spirits”) point out, drinking and alcohol (especially “spirits”) serve multiple purposes, some of which might be essential. Does the novel exemplify the virtues of drinking and alcohol? If so, what virtues in particular do the teetotalers need to recognize? If not, why do drinking and alcohol seem so useful during Stephanie’s experiences?

CP: Being ex-army, Stephanie is very aware she’s self-medicating with how she drinks. I knew that from very early on that part of her keeping her control is relinquishing control in the sense of letting herself drink so she has something to ease the edge of what’s happening to her because thinking about it too much would crack her head like an egg. As such I think there is a critical edge to what she’s doing, but she’s taking the approach of doing something bad to prevent yourself from doing something worse. If that’s the right choice, that comes down to everyone’s own take, but I can understand why she does it.

I think there is a certain level of virtue in her use of the alcohol, but most of it is prevention rather than cure because this is not a curable situation! She does utilize it as a tool, in the medical sense, and that does surprise the hotel somewhat despite it giving her the alcohol to begin with. There’s only one real instance where the alcohol helps her out, though, and she gets punished for that by the Basker because it hadn’t expected that level of resistance. Equally, her breaking out the old army methods – both in the sense of wound tending and self-medication – helps keep her in her own mind rather than spiraling, so I think there’s a virtue in that as well.

4. Haunting Time. Time works differently in the Basker, perhaps even running at different rates for different inhabitants. Why? Stories that involve the supernatural often depict time anomalies related to ghosts and haunted places. Why does this aspect of the haunting tradition fit with your work, and why do you think it has become such an integral part of people’s conceptions of supernatural phenomena? Without giving too much away, how would you describe the way time functions for different characters in the Basker? What causes the anomalies?

CP: Oh, I loved playing with time in this story. Time is absolutely different for different ghosts and other guests because the Basker doesn’t treat everyone equally, both in terms of preference and extent of power. A living human in the hotel is not the same as a ghost is not the same as other occupants, and Stephanie is a horrible little anomaly for the Basker because she’s not doing what it wants. The Basker absolutely expects her to give in after a day or so, and instead she sits there like a limpet at the bar, seething with hatred, stubbornly refusing to die. That takes more energy and means she’s both a torment and a prize for the hotel, which we see in her interactions with some of the ghosts as well. I especially think this shows later in the book because Stephanie’s sense of time really zones down into sleeping and waking, and the thin edge of if dreams are real or not, which comes back to reality with a crunch near the end.

Living in Scotland, the idea of time changing and slipping is a very natural thing. When you have days with only 6 hours of light (not guaranteed to be good light), or conversely days in the summer where the sun never goes down and you’re still hearing birdsong at midnight, it’s natural for things to feel a little fae.

5. Haunting Imagery. Treasured Guest delivers stunning imagery as Stephanie encounters supernatural phenomena. What inspired your imagery? The very effective descriptive writing often aims to construct—I’ll call them “entities”—in readers’ minds for which readers have no reference points. In other words, readers have never seen anything like these entities, so you must build them in readers’ imaginations from scratch. How do you do that? For me, the radically unfamiliar images cross from the grotesque to the surreal. Did you consciously seek surreal effects, and/or do you think of Treasured Guest as surreal? Why or why not? The Basker builds psychological tension by changing the art on its walls, which, like Treasured Guest’s descriptive passages, gets increasingly violent. What might this haunting parallel between the art in the story and the art of the writing mean?

CP: Each entity landed very firmly as what they were when I was writing the story, though they all tie into part of what Stephanie is going through when they haunt her. The horned men, for example, are easy to draw comparisons with things she will have seen in her previous life in the army, though her comrades probably didn’t have quite as many extra parts, and poor Eric is an echo of Stephanie’s own despair, though she chooses a different path. The most constant is the delightful company of the pit, and I really wanted the reader to feel the presence of that even when it’s just dark and hungry rather than actively enticing, as it can be.

Surreal is very much part of the book – the hotel revels in breaking reality around it, so some things simply have to be surreal as they’re outside of reality. Stephanie spends her whole time in the suite eating bar cherries because there’s no other food, which is deeply practical in the face of what’s happening, but her little habits of clinging to reality keep her from slipping into the same bizarreness the Basker is trying to lure her into. I’m not sure I think of the novella as capital-s Surreal, but the hotel does delight in the fuzzing of lines between dream and nightmare, worldly and ethereal, so it has to be walking in the shadow of surreal.

The art was absolutely how I wanted the hotel to talk, given it doesn’t have a “real” voice in the sense that other things in there do. The art is both a conversation the hotel is having with Stephanie and an extra pressure it’s putting on her, overwhelming or undermining her through the space she has to traverse to get help and her needs met in the suite. The art changes not only to reflect when it’s angry with her, or needling a wound, but the type of art changes, too, and escalates as she lasts longer in the suite. One of my favorite parts of this is a small statue we see, deeply lonely in the first instance, and then bloody and cruel when the hotel wants Stephanie to feel small, and her rejection of that is a very powerful moment for me because she doesn’t shy away from that pain, but she doesn’t let it consume her, either.

6. Haunted Hero. Stephanie has a military background that helps her survive assaults from the Basker’s more aggressive denizens. This background is important for the plot, but what should it help readers to understand about her character? Stephanie’s stay in the Basker ultimately becomes a pitched battle for survival, and her preparedness for such a situation makes your book resonate with a subgenre I never expected going in: survival horror. Did you think about survival horror while writing? Do you think “survival horror” is a fair label? Why or why not? Stephanie’s background has also left her with PTSD. How should knowing that fact affect readers’ perceptions of her? Of the reliability of her perceptions?

CP: Stephanie being ex-army was less of an active planning choice (I’m a pantser for life, alas), but it did come through very strongly with her character at the start of writing. I think this background explains a lot of her little checking in touches – her packing routine, still honed from being used to travelling, checking in with travel before she’s out of the hotel, knowing how to navigate travel with her hangover, all speak to a preparedness that hasn’t fallen away despite her change of career.

I always knew Treasured Guest was a survival story of sorts, so I do think survival horror fits, though it wasn’t exactly what I expected when I started writing it. I certainly think Stephanie’s PTSD is very controlled, but part of that is the balancing act with her drinking. If she doesn’t keep her mental boxes from falling open, she’s very aware she could lose control, and she’s in an extremely hostile environment, so that knife edge of relying on training and letting herself fall back into old habits like keeping armed and tending her own wounds helps her but leaves her at risk in new ways. I always wanted to keep that balance of choosing which thing would be worse and trying to keep the balance, though the Basker has no intention of making that easy!

7. Being Chosen and Being Queer. Stephanie has a longstanding girlfriend, Jenny. Why did you choose a queer hero? Before she learns that the Basker has chosen her to be one of its inmates, she reveals that her boss chose her for the trip to Glasgow because, instead of being in a relationship with a man that has produced children, she is in a relationship with a woman raising cats. Is a heterosexist bias responsible for sending Stephanie to the Basker in the first place? Why or why not? If there is a connection between Stephanie’s queerness and her selection for the trip to Glasgow, does it parallel her selection by the Basker? If so, what do the parallels mean? Stephanie’s thoughts eventually reveal that she had “little choice” but to leave the military once her relationship with Jenny was discovered by military police. Might Treasured Guest say something about queerness and choice? If so, what?

CP: I’d love to have an original answer here, but I’m queer and I love writing other queer characters because I want more of us out there! I do have the occasional straight hero, but most of mine are rolling around in the rainbow, and it seems likely to be that way for the foreseeable future.

Stephanie being sent off because she doesn’t have children is a real-life lift from something that was said to me previously! I was volunteered for a work matter four hundred miles away from the office when other – more qualified – people could have been sent, despite my long-term partner being a chap. I suspect it’s something a lot of people bump into, still, their relationships being minimized into “very good friends” or “tiding over”, etc. So yes, it was alas heteronormativity all along, and it’s still alive and well.

In terms of how it reflects on the Basker choosing her, I certainly think it would see itself as an equal opportunity employer, so to speak, but it’s more interested in what Stephanie can do. It’s quite willing to play on her preferences, such as Frankie the bartender, but that would be more to do with it being a good predator than having any love for a particular alignment.

Stephanie having to leave the army is another real-life lift! Until 2000 you couldn’t be gay in the army in the UK, it was illegal, and we had some fantastic people being forced out of careers they’d worked very hard for because of who they loved. Sure, there were open secrets that went on, but anything tangible got you out and revenge outings and the like very much happened. So, there is certainly an emphasis on choice for Stephanie – she already knows what she’s willing to live through and has lived through before in choosing her relationship with Jenny. I think that level of self-knowledge is a great strength for her and informs what she’s willing to do to survive, but I also think that being willing to fight for a life that you’ve made and value comes into play for a lot of people.

8. The Pit, the Void, and Suicide. After Stephanie is in the Basker’s trap, she seeks a way out, and hotel personnel present her with three options: jumping in what looks like a dark, bottomless pit; surrendering to a void that seems to consume all that it touches; and suicide, which would lead to her body being cannibalized and… likely other horrors. Why must she face such apparently bleak options? No spoilers, but, at least symbolically, why the apparent opposition between the pit and the void? Is suicide a reasonable option? Why or why not? Either way, the possibility of suicide looms over much of the story. Why? We live in the age of trigger warnings. How do you feel about trigger warnings? Do you feel like Treasured Guest needs a trigger warning for suicide? Why or why not?

CP: The Basker doesn’t get good team members by giving them good choices! It consumes those it chooses because it wants the best, but that requires a level of acceptance for both parties – you have to jump into the pit, you have to willingly give yourself over, to be fully ingratiated into the “family.” And to reject such an offer has to mean the worst punishments, which to them is the unmaking of the void. Why would you surrender to oblivion when you could be so much more? This is obviously a false choice, but we are in a world with so many false choices presented as essential, and Treasured Guest is certainly happy to lean into that and show why we don’t have to make a choice we’re being forced into.

How reasonable can suicide be? There’re certain characters in the book that would argue either side of the line for whether suicide is a valid option – Stephanie possibly being one of them as a veteran. UK veteran suicide rates aren’t as bad as in the US, but they’re not great. One of my cousins killed himself after he couldn’t get what he’d seen out of his head, so he cracked it open. It’s hard when people do that, for them and everyone around them, and I think Treasured Guest presents suicide as a form of agency – to escape the Basker – but with its own risks and pain, which I wanted to highlight, too.

Suicide is certainly something that is strongly present, but I think it would be unrealistic for it to be absent. Stephanie is aware that there are worse things than death and was before the hotel, given she’d seen combat previously, so it would always be something that’s an option. But she also always has something she doesn’t want to give up – Jenny and her life, the ability to be herself openly now, and that’s a strong anchor for her. So, there is a hopeful element to Stephanie as well.

I’m in favor of trigger warnings. If they help someone have a better experience then that’s got to be a good thing, but ho boy yeah Treasured Guest comes with quite a few! I think when I was submitting it, I warned for graphic violence and gore mostly, but I wouldn’t feel bad about one of suicidal tendencies being present either.

9. “Defiance Against the Absurdity.” On the subject of voids and suicide, a lot of Treasured Guest seems to me to be about existential issues. Is it a philosophical novel in disguise? I’ve asked questions speculating about reasons, but to what extent is the Basker’s “choice” of Stephanie about randomness, or at least the appearance of randomness? Stephanie often perceives what is happening to her in terms of “absurdity” and the “ridiculous,” and she tries to avoid succumbing to the “insanity.” To what extent is the absurdity Stephanie faces the Absurd? Is “defiance against the Absurdity” (your words, capital A added) Stephanie’s supreme virtue? Why or why not?

CP: You can’t have cosmic horror without a good dose of existential issues, that’s part of the fun! And some good existential dread leads us nicely into philosophy, depending on who you like to read. I tend to lean more Robert W. Chambers and Ligotti than Lovecraft, but I don’t think you can tackle good cosmic horror without rolling around with some of the questions that raises.

Is Stepanie special or just very unlucky? I would say she’s a bit of both. She has an excellent set of skills, that she’s worked hard for and honed, and that just happens to be what the Basker wants. Does that make her special? To go back to Chambers again, and his quote of “what a terrible thing, to be noticed by a god”, can there be any good result of something so powerful recognizing you as interesting? Do the spiders we spot know we might go and get a glass to let them go rather than just killing them? They run away just the same, and Stephanie certainly hasn’t found her “glass” very appealing, despite the well-stocked bar.

I do think Stephanie’s unwillingness to give up her own sense of order is one of her great strengths in the book. She knows what is happening is a little bit impossible, but that doesn’t mean she has to agree with it or go along with it. This is especially present in her issues with the bathroom, because that really interferes with her ability to make things feel normal, and the scene with the towels is one of my favorite instances of that. I also think, as someone who is self-aware of her PTSD, she’s worked very hard at knowing what is real versus what is the rattling of a box in her mind, and the Basker’s willing chaos doesn’t have the same impact because she is quite regimented in grounding herself in reality. I don’t know if that makes it a virtue as much as her supreme survival tactic, because not everyone would agree with her methods for remaining alive, but I think it’s certainly her strength.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

I have a website which is https://charlotteplattwriter.co.uk/ and the mandatory Amazon page, or you can find me on the following:

Twitter & Bluesky – @Chazzaroo

Insta – chaz.platt (this is mostly dog photos, I warn in advance)

Tumblr – Chazzaroo47

About the Author

Charlotte Platt is a dark fantasy and horror writer based in the very far north of Scotland. She earned her Master’s in Creative Writing through the Open University and has had around fifty short stories placed across various anthologies, podcasts, and essay collections. Her most recent novel, One Smile More, was released in June 2024 through Grendel Press. When she isn’t out beside the river looking for herons, she can be found walking her parents’ rescue dog, Joe, or tending to her garden – both of which feature heavily on her socials. Outside of writing she likes live shows, comedy, and music, as well as researching deep dives for her next novel.