Scheming white male politician.

The final word implies the first, and if you’re in the U.S., the power players are still mostly of the middle description (one President doth not a norm redefine).

Combining the four words, then, produces maybe two-and-half words’ worth of meaning, and that meaning is, considering the history of global empires, nothing uncommon. It should hardly hold fascination.

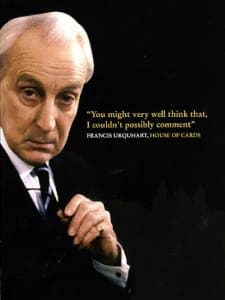

And yet behold Ian Richardson as Francis Urquhart, the fictional post-Thatcher politician who manipulates his way through British politics by any means necessary in the original three UK House of Cards series (1990, 1993, 1995). As the poster suggests, the show depends utterly on his diabolical charm. His charm stems in part from the transparency, enhanced by his direct addresses to viewers, with which he flaunts strategic contradictions between unofficial and official discourses in his catchphrase, “You might very well think that, I couldn’t possibly comment.” More than that, his charm stems simply from his comfortable abuses of power. He behaves entitled, and by golly he does seem smarter than everyone else, so perhaps he is… and yes, somebody might die now and then, but these things happen.

And yet behold Ian Richardson as Francis Urquhart, the fictional post-Thatcher politician who manipulates his way through British politics by any means necessary in the original three UK House of Cards series (1990, 1993, 1995). As the poster suggests, the show depends utterly on his diabolical charm. His charm stems in part from the transparency, enhanced by his direct addresses to viewers, with which he flaunts strategic contradictions between unofficial and official discourses in his catchphrase, “You might very well think that, I couldn’t possibly comment.” More than that, his charm stems simply from his comfortable abuses of power. He behaves entitled, and by golly he does seem smarter than everyone else, so perhaps he is… and yes, somebody might die now and then, but these things happen.

Francis Underwood in the U.S. House of Cards (2013 – ) plays a bit rougher, and instead of dark British wit, a sort of post-capitalist nihilism animates the more recent American series, but the center is the same: the diabolical white politician’s inevitable rise to power through amoral out-thinking of opponents. Here, delightfully bad FU is embodied by Kevin Spacey, who, lest we forget, broke out via diabolical turns in Seven (1995) and The Usual Suspects (1995).

Younger and more traditionally attractive than Ian Richardson (relative to the times when playing the role), Kevin Spacey’s charm–physical, no doubt–nevertheless comes from the same place as Richardson’s when inhabiting FU: power. Good old-fashioned white patriarchal privilege. Kind of like romanticized images of the white side of the antebellum plantation (only appropriate that American FU is from South Carolina), each of these men is a fantasy of a fading phallus still shining mighty in its twilight years.

Younger and more traditionally attractive than Ian Richardson (relative to the times when playing the role), Kevin Spacey’s charm–physical, no doubt–nevertheless comes from the same place as Richardson’s when inhabiting FU: power. Good old-fashioned white patriarchal privilege. Kind of like romanticized images of the white side of the antebellum plantation (only appropriate that American FU is from South Carolina), each of these men is a fantasy of a fading phallus still shining mighty in its twilight years.

More than that, each of these men is a fantasy that maintaining long-held privilege no matter the cost is somehow an ethical act. FU is so damned smart, charming, and yes, sexy–more on that in a moment–that neither show has to work very hard to make him an antihero, the sort of person who pulls off such outlandish schemes that you can’t help but root for him to get away with it (after all, it’s only TV). And he’s so good at it that you kind of have to admire him. I mean, there has always been some attraction to utilitarian thinking, the ends justifying the means and all that. Machiavelli was no slouch. Politics isn’t always about making friends. One of the American show’s taglines is “Bad, for the greater good,” so the show is pretty up front about inviting utilitarian ethical identification–or at least suggesting utilitarian calculation as an excuse for identifying with the egotism of either wanting to be or to remain the ruling elite.

The top of the ladder appears nowhere more mysterious and attractive than from the bottom, something that House of Cards on both sides of the pond demonstrates via sexual trysts between FU and women young enough to be his daughter. In extremity, the British version wins this point.

While daddy issues arise in both versions, the British version has the young lady call FU “Daddy” as a pet name in bed, and she also calls him by that name in one of the series’ most pivotal moments.

While daddy issues arise in both versions, the British version has the young lady call FU “Daddy” as a pet name in bed, and she also calls him by that name in one of the series’ most pivotal moments.

Not to be outdone, however, the American version also adds a son to the equation. Developing FU’s wife, Claire Underwood (portrayed magnificently by Robin Wright), as a much more significant character, the show adds a young, faithful security agent to the Underwood household. They treat him like family, and then, naturally, they fuck him.

While a typical reaction might be to look at the FUs and think about the reasons why aging white male politicians can’t help fucking people half their age (cf scandals too numerous to name), it might be more instructive to think about why these young people can’t help fucking these old guys.

The white male regime’s days are numbered–the prejudices that animated its power base are just becoming increasingly visible in their ridiculousness (and I’m a white male, so I’m commenting on my demographic’s historically disproportionate hold on power, not on anything inherently wrong with white dudes). Younger people these days are increasingly more likely to vote their conscience over the color of their skin or their sex/gender, which means the ONLY way “scheming white male politician” is going to continue to be an oddly redundant phrase is if said schemers use increasingly vile Machiavellian tactics. The dealings of FUs that play the political system against itself (like, say, ensuring that Congress is unproductive in order to provoke general outrage at the government) are pretty much the only means available for the privileged white male regime to prolong its hold.

So in the fantasy of the aging Machiavellian sex god, the young people look up to the top of the ladder and see not a generation of ineffectual self-promoters clinging to outmoded wedge-issues but embattled deities, grasping at thrones, the unlikeliest underdogs, irresistible in their brutal willingness to do anything and everything to survive just as they are.

The House of Cards devils aren’t alone. Machiavelli himself appears as a character alongside Jeremy Irons’ wicked portrayal of a hyper-sexed Pope in The Borgias (2011 – 2013). With credits such as Damage (1992) and Lolita (1997), Irons is no stranger to playing the wicked older seducteur, and he blends a kind of infantile obsession with sex into a politically brilliant and morally layered character that is almost difficult not to admire, despite the utter reprehensibility of much of his behavior.

More recently, another aging sex symbol has added a twist to the mix. The second season of The Blacklist (2013 – ) is underway, starring James Spader as Raymond Reddington, an international supercriminal, murderer of an untold number, now working with the FBI likely as part of a conspiracy yet to be fully revealed.

Spader– Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), White Palace (1990), Crash (1996), and Secretary (2002), to name a few–has been smoldering with a certain sex appeal for quite some time, and he breezes through scenes in this show with all eyes longing after him. His character–unlike the high-ranking politicians of the House of Cards series or the Pope–is someone who works outside, and arguably even above, the law. This variation on the fantasy of the aging Machiavellian sex god presents an alternative that the others, perhaps, do not consider. Instead of manipulating and breaking the laws that the others variously make and execute, Reddington gets to ignore the idea of laws completely. This solution, to some, could seem ideal: when the law no longer suits the ruling elite, the ruling elite no longer have to obey the law.

Spader– Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), White Palace (1990), Crash (1996), and Secretary (2002), to name a few–has been smoldering with a certain sex appeal for quite some time, and he breezes through scenes in this show with all eyes longing after him. His character–unlike the high-ranking politicians of the House of Cards series or the Pope–is someone who works outside, and arguably even above, the law. This variation on the fantasy of the aging Machiavellian sex god presents an alternative that the others, perhaps, do not consider. Instead of manipulating and breaking the laws that the others variously make and execute, Reddington gets to ignore the idea of laws completely. This solution, to some, could seem ideal: when the law no longer suits the ruling elite, the ruling elite no longer have to obey the law.

The ruling elite have simply become too sexy to be ruled.

Comments are closed.