Since Stoker, about which I am appropriately stoked, has not yet come to Louisville, the horror movie this weekend was The Last Exorcism II.

Ashley Bell struggles with monstrous talents in The Last Exorcism II.

It’s a pretty by-the-numbers white-girl-under-demonic-threat sort of thing, but delightfully cheesy developments toward the end, especially with awkward use of digitally-generated fires, yield a distinct type of pleasure. The film’s greatest pleasure, however, is the masterful performance by Ashley Bell. While I’m pleased when real acting talent gets involved in my genre, horror’s tendency to reduce the living to the soon-dead does not usually allow an actor to develop reasonable emotional depth. The depth of most horror is in the body, not the soul, and we gain access to that depth through cutting implements, not talented expression. The Last Exorcism II doesn’t really need good acting talent, but it has it in Bell; I hope the film will do well enough to get Bell gigs in situations where her gifts will be more fully realized.

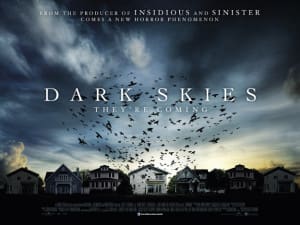

White house, white family–singled out by the terrifying bird threat from non-white skies.

White house, white family–singled out by the terrifying bird threat from non-white skies.

Last Exorcism II connects in surprising ways to the horror film of last weekend, Dark Skies. In each film, persecuted protagonists are inside either a church (Exorcism) or a suburban family home (Dark Skies) when some birds, either through brain damage or insidious supernatural control, kamikaze the building. In each film, it is the first, clearest sign: we are fucked, ladies and gentlemen.

Hitchcock’s birds get in line to terrorize privileged white people.

No image of birds gone amok can evade evocations of Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). But while Hitchcock’s haunting imagery–one of the best apocalypses in the history of film–shows the birds turning on humanity tout court, the angry birds in these films target only certain embodiments of cultural privilege and assumption, namely, white suburban families.

This targeting is clearer in Dark Skies: it’s fundamentally about upper-middle-class people threatened by an inexplicable Other that wants to knock them out of their proper place in the natural order.The film takes a quite boring turn when it resorts to aliens a-la Whitley Streiber’s Communion,but it is nevertheless relentless in its political representation of normative bourgeois family life. A successful architect father-of-two feels the pain of the crashed economy and has to look for a job, which he finds with relative ease–at least it’s an acknowledgment of joblessness, but architect-level privilege hardly represents the struggles of most people in the post-2008 financial miasma. This well-to-do family still thinks it is downtrodden, though; they feel victimized by cultural circumstances, and they are more victimized as their son shows too much interest in video games and pornography and not enough interest in the values of developing the family unit. Without giving too much away, I’ll say that the son’s deviant (heterosexual) interests become, somewhat inexplicably, a central feature of the film’s climax. Within this depiction of an alien threat coming from dark, godless skies, a larger threat associated with challenges to family values beams through clearly. Narrative logic flies out the window, but a right-wing logic that uses, for political purposes, images of the white heterosexual nuclear family under threat… that logic is remarkably coherent. Dark Skies is a nightmare about the normative white, heterosexual family unit being destroyed by outside forces that are just too different to fight or even understand. It is the same nightmare that repeatedly turns right-leaning straight white Americans against Muslims, gays, African Americans, and other minority groups who might look funny in the cul-de-sac.

Readings of Last Exorcism II in relation to similar white bourgeois values and prejudices are necessarily weaker because Ashley Bell’s character, Nell, comes from poor country folk, and the halfway house she ends up joining in New Orleans, shown still resenting FEMA’s (or perhaps Katrina’s) destructive visit, is hardly a site of privilege. Yet Bell plays her character as reserved and demure, a stark contrast to her fellow lower-class orphans–she’s a good little virgin, ready for the proper marriage market. Her white female body is, in a quite standard way, the site on which social contests, here figured as demon versus man, play out and lead to social elevation. And again I don’t want to spoil too much, but it’s worth pointing out that while Dark Skies focuses on the nightmare of suburban white folks losing their claim to power, The Last Exorcism II focuses on the nightmare of the contested figure, the white girl blooming into a sexuality exceeding social norms, crossing over into non-normative ranks. Both films, then, center their horrors on the loss of white privilege and white control of the suburbs, the churches, and bourgeois white folks’ ability to reproduce their own social standing. White flight into the suburbs hasn’t worked. White gentrification of poor urban areas hasn’t worked. The demons of otherness follow our white heroes everywhere, and horror of horrors, the white have to keep moving to maintain the illusion of supremacy.

So, then, what of the birds? Why do the imperiled whities in both films have to confront a bunch of birds dive-bombing places that should be their refuges? As with Hitchcock’s birds, these birds can be manifestations of psychosexual repression, the revenge of nature on the unnatural ways of humanity, eruptions of the unconscious that assert the primacy of irrationality and thereby destroy all assumptions of the Age of Reason. All these things, yes, but more–angry birds, so popular in our techno-culture right now, are Others, figures of the threat now faced by traditionally hegemonic functions of whiteness and heteronormativity, but they’re Others not as obviously equatable to a specific demographic group. In that sense, angry birds are politically correct bad-guy stand-ins for the scary things nice white people don’t talk about anymore.

Birds are angry. And they’re coming for us.

Black people are not the problem here. Gay people are not the problem. The usual scapegoats, if they appear, appear to do more good than harm. Instead, we have nature itself, birdiness, attacking our white supremes. Nature itself rejects white power and heteronormativity. I’m not saying that in these films the rejection of the oppressors appears to be a good thing. On the contrary, the oppressors’ rejection seems quite scary. These films are the nightmares of what’s happening now, of an economy that dares to touch even our highly talented upper middle-class architects, of growing racial and ethnic populations that turn city after city into pluralities gradually learning to challenge white majority rule with darker-skinned horizons. The birds are politically correct in being no particular Other, but they become all otherness. Privileged white people recognize that the humans who oppose them might have good reason to contest the country’s unfair distribution of resources. They don’t want to do anything about it, of course, so they just have nightmares of the masses–of birds threatening their homes and churches. No one in particular is after them. White people face a generalized badness, Angry Birds, as they face their hegemony’s decline. And these by-the-numbers horror films allow us to see just how horrific social progress can be to those who have the most to lose.

Comments are closed.