Dramatic sieges against the home, mounted by villains of various stripes, have been cinematic mainstays at least since hunters have had nights and fears have had capes. In fact, horror/thriller sieges waged by monsters and killers are echoes of the sieges waged by dastardly Injuns and others who would thwart the white man’s destiny. Therefore, giving in to the temptation to start this blog by mentioning the “recent” turn toward home invasion in mainstream horror films seems to have way too high a cost in credibility.

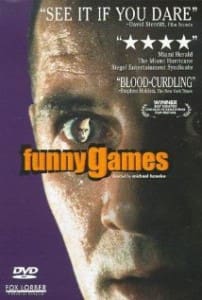

So the home invasion thing isn’t recent, but we have had a recent hybridization of classic home invasion with torture porn, a kind of pseudopod of horror’s post-millennial flirtation with decadent extremism. Consider it a logical mutation: instead of you going to a trap (Saw 2004, Hostel 2005), the trap comes to you. The Collector (2009) is the best connector film here for both on- and off-screen reasons, but somehow the most iconic popular home invasion film is The Strangers (2008), which is arguably indebted to and certainly similar to the French film Them (2004). On the side of the universe more acceptable to the art circuit are Michael Haneke’s two versions of Funny Games (1997, 2007). These films (among others) deal with people coming to the protagonists’ home and wreaking outrageously violent havoc.

On June 7, the film The Purge (2012) entered this filmic pseudopod with a well-advertised twist: instead of being randomly kidnapped (Saw and Hostel) or randomly invaded at home (Strangers and Funny Games), these people must deliberately, preparedly defend themselves because it’s the one special night of the year when murder and every other crime are legal. So the haves better have some bulwarks against the have nots.

The Purge‘s focus on the reason, the causal context (“The Purge” is the event, the night, when law is suspended and the narrative conditions are possible) is what makes the movie stand among the best of this pod. Nevermind Ethan Hawke’s good performance–after this one and Sinister (2012), I’m hoping the Genre Has Him–the writing, production values, and cinematography are all interesting enough to rate words like “skilled” and “above average.” Costume design and make-up get serious thumbs up, too.

But the film’s slick goodness alone wouldn’t earn it many bytes in the brain if that slickness didn’t deliver, loud and clear, a message that the other films have been mumbling all along. In Funny Games, people hunt people because excess of privilege devalues life… if we read the ambiguous bad guys in a certain way. In The Strangers, the anonymity of wealthy ranches spaced out along large plots of land makes people isolated and interchangeable (in the near future, you will all be reading brilliant things by Katherine A. Wagner on this topic)… but the film gives no frame of reference for protagonists, antagonists, or locations, so pinning it to particular politics is challenging. With The Purge, no more ifs, and no more hunting for frames of reference [INDIRECT SPOILER ALERT]: it’s about inter- and intra-class warfare projected forward from variables with which we are very familiar. It very carefully lays out issues of race, gender, economics, generational value shifts, freedom vs. security, and so on, and diegetically, it lets people fight them out for a little while.

Ultimately, I think I prefer the crazy ambiguities of Funny Games (not to mention other unmentionables), but that film… those films… also trade a lot on style, whereas The Purge trades on fusing levels of emotional and political catharsis and is, on the whole, very successful. It also uses fairly painless references to its podmates–masks that evoke The Strangers and a lead bad guy who could be one of the young gents from Funny Games–to tell viewers paying attention that it is continuing a conversation about violence, a violence arguably reducible to the fundamental structure of society, begun in the earlier films. And The Purge is not afraid to be un-subtle about structure-of-society stuff while still thrilling us with a delightful violence of its own. That earns my respect.

Comments are closed.