Interview with Filmmaker Alexander Deeds: “Jumpin’ Jacob” and “Butterscotch” (2024)

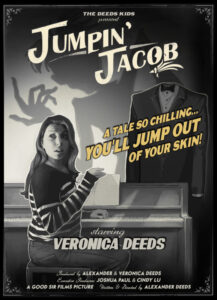

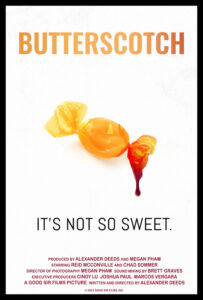

I first encountered Alexander Deeds’s filmmaking while I was working with the Miami International Science Fiction Film Festival (MiSciFi), 2024, where his film “Butterscotch” took home the prize for Best Horror Short. Here we discuss “Butterscotch” along with his earlier short “Jumpin’ Jacob,” which is also brilliantly creepy. You can watch both films by linking through their posters–highly recommended!–and then enjoy insights from an artist who is definitely one to keep watching.

“Jumpin’ Jacob”

“Jumpin’ Jacob” is a film about haunted music, where the focus is just as much on the silence as it is the sound. In a genre so filled with loud bangs, we wanted to make a film where the gasp of the audience was the loudest part of the soundtrack.

“Butterscotch”

“Butterscotch” is a bite-sized horror short, centered around a Bully who picks on the wrong person: a seemingly comatose Old Man in a nursing home. This is our take on a Grimm-style story, and we hope it follows in that tradition of teaching a moral in a deliciously scary way.

The Interview

1. Nonverbal Horror. Though neither is silent, and “Jumpin’ Jacob” involves significant and significantly creepy song lyrics, both “Jumpin’ Jacob” and “Butterscotch” are dialogue-free and nearly nonverbal. What draws you toward the nonverbal? Did you bother with conventional screenwriting for these shorts? Why or why not? How does the absence of speech relate to horror in the scenarios that play out in your films?

AD: On Jumpin’ Jacob, the initial idea was to make a horror film that was centered around sound and silence, and where the music itself was the main character. When you want the song to be the main focus, you quickly realize that any other music you include can start to fight it for attention. That’s why we ended up not using any kind of score, and why there’s only one fairly simple song on the Girl’s CD player. We want JJ’s song to be the star. And with that in mind, if you consider dialogue to be its own form of music, then going nonverbal just made sense. It was a great lesson for me: What you remove strengthens what you keep, and we carried that lesson over into Butterscotch. The central idea of that film was the creepy tension of sustained eye contact; it’s awkward and strangely tense, and I think a lot of people would talk to alleviate that tension. But remove the dialogue, and that tension just keeps building. I did initially try to write a couple lines of dialogue to explain why there’s a kid walking by himself, but everything I wrote just felt unnecessary. You get the idea just through the visuals and the characters’ blocking, so that’s ultimately why it’s another silent film.

2. Tenterhook Tension. Both films build tension masterfully—how do you do it? We’ve already started talking about playing with silence and sound. What additional techniques do you use (cinematographic, editorial, etc.) to create suspense, dread, and fear? The “Jumpin’” in “Jumpin’ Jacob” had me bracing for a jump scare from the beginning, and you deliver effective jumps in both films. What attracts you to jump scares, and why do you think they’ve become so popular in contemporary horror?

AD: When it comes to building tension, I think one of the most effective ingredients is to trap the audience in the character’s very limited subjective experience. In both my films, the visuals and editing are almost entirely from the character’s POV, and you’re just as clueless and in the dark as they are. There’s no objective camera giving you nice establishing shots of the house to orient you. We’re living in a shot/reaction-shot world, where we see the character look at something off-screen, and then we cut to see what they’re seeing, and then we cut back to see the character’s reaction.

To elaborate further: I watch a lot of horror movies, but I rarely ever get so scared that I need to turn the lights on. If I do, it’s always because I’m watching a “found footage” movie (something like The Blair Witch Project, for example). In those films, you’re only seeing what the camera sees, and nothing else. No musical score. No cutting to ten different angles around the room. Nothing we’ve come to expect to remind you you’re just watching a movie. That very limited point-of-view can start to feel claustrophobic to an audience member, to the point where it can trick your lizard brain into thinking it’s your point-of-view, too. I like to live in that world even if I’m making a more traditional horror film, because they’re the ones that can viscerally grab you in a way that’s truly unique to horror.

3. Accented Eyefuls. In both films (but perhaps more pronouncedly in “Butterscotch”), set design and color palettes seem painstakingly planned and carefully detailed. With specific reference to the settings and color palettes you use, what effects do you expect these aspects to have on viewers of “Jumpin’ Jacob” (the yellows, for example)? Of “Butterscotch” (the blues, for example)?

AD: Jumpin’ Jacob’s yellow theme was to reference the aged paper of the titular sheet music – and JJ’s “skin” by extension. It was my way of keeping his presence on-screen, even when you don’t see him. For Butterscotch, the intention was the complete opposite: I wanted the candy’s presence to be small but *pop* out of the screen. (If you’ve seen the movie, you know that *popping out* is a recurring theme.) That intention led us to remove all other yellows from the film, and to really lean into the cooler blues.

It was the most I’d ever played with color in a film, and it really reinforced the lesson I learned on JJ: What you remove strengthens what you keep. As a bonus, the blues also helped create an atmosphere of a rainy, overcast day, even though we never look out any of the windows.

4. Attempts at Alignment. What I like most about both films’ narratives is that they have that ineffable quality of being genuinely different, yet I cannot resist the urge to connect them to traditions (it’s a thing I do). Both deal with the sudden eruption into the ordinary of something supernatural, monstrous, and deadly. Campfire tale? The erupting force has an aura of lore. Urban legend? Creepypasta? Something more surreal and/or disturbing? What do you make of any or all of these possible kinships with your films? You call “Butterscotch” “Grimm-style:” would you also liken “Jumpin’ Jacob” to a fairytale? Why or why not?

AD: I really appreciate the compliment, thank-you! Between the two titles, Jumpin’ Jacob was definitely our contribution to the classic boogeyman and haunted house traditions, though with a musical twist. I think it would feel at home in any of the traditions you mentioned, especially in the Creepypasta world, which we were definitely conscious of (Slenderman walked so we could jump). But where JJ is the more traditional story, I wanted Butterscotch to feel like it could exist in its own weird corner, in good company with something like Courage the Cowardly Dog. In fact, the thing I’m most proud of with Butterscotch is that we were able to pull off that off-kilter tone, and I am beyond proud that we assembled a team where everyone was committed to making the same weird movie.

5. Morality Moves In. In “Jumpin’ Jacob,” The Girl doesn’t seem guilty of any moral infraction, but in “Butterscotch,” Bully is, well, a bully, and (speaking of fairytales) as your description emphasizes, “Butterscotch” delivers a moral. What difference does the absence or presence of a moral make to the horror factor in each film? Are we supposed to take pleasure in the fate of Bully (schadenfreude!) that we can’t in the fate of The Girl? If we take pleasure in either, what does that pleasure say about us?

AD: Having a moral or message in my films has never really been a goal of mine, unless it’s what felt right for the story. For Jumpin’ Jacob, for instance, I love that the Girl stumbles into the horror innocently; her only fault is being in the wrong place at the wrong time. There’s a great quote from The Mothman Prophecies, where Richard Gere’s life has turned upside down after a car accident puts his wife in the hospital: “One day you’re just driving along in your car, and the universe just points at you and says, ‘Ah, there you are, a happy couple. I’ve been looking for you.’” It’s one of my favorite quotes, and that horrific randomness helped to inform what happens to the Girl. For Butterscotch, on the other hand, I wanted to try something different. Watching movies as a little kid, I was always the most scared when the bad guy was about to get their comeuppance. I can’t really explain it; there was just something about seeing them meet their horrible end that affected me more than the other characters. Beni’s death at the end of The Mummy was one that really got under my skin (If you’ve seen the film, you’ll appreciate the pun). And I wanted to bring that creepy crawly morality to the Bully in Butterscotch. But also, in all honesty, I think I made the Bully so cruel because it would’ve just been mean-spirited to pick on a little kid who did nothing wrong.

6. Fear of Age. In “Jumpin’ Jacob,” scares start when The Girl discovers worn sheet music for an old-fashioned, Jazz Age style song. In “Butterscotch,” Bully, a boy, gets in trouble when he picks on the aptly named Old Man at a nursing home. Youth encountering age, with the old eventually becoming the source of something scary, lies at the center of both films. Is this connection deliberate, and whether or not it is, what do you think about it? What specific fears about the old do you think your films might draw on?

AD: When I was a little kid, there was an old woman who lived next door to us; she was a very sweet old lady – who would sometimes scare us by popping out her dentures. That image of her laughing, holding her teeth in her hand, was burned into my brain, and I’ve been returning to older characters ever since. Of course, Butterscotch follows in a long lineage of creepy old people, most notably the witch in “Hansel & Gretel,” whom you could see as a direct predecessor. But beyond just the body horror element, it’s also the Hector Salamanca archetype: the quiet old man in the wheelchair who was something completely different, and maybe even monstrous, in a previous life. There’s just something haunting about what’s come before, and I’m drawn to stories where that something reaches out to grab us.

7. Jazzy Jacob? Speaking of the song in “Jumpin’ Jacob,” why did you choose its particular style, and why is the design for Jumpin’ Jacob right for it? What makes JJ so scary looking?

AD: I can’t really explain why, but if ghosts were a genre of music they would be 1920s jazz, calling out from beyond the crackling vinyl. It probably has a lot to do with The Shining and Jeepers Creepers. There’s just something about jazzy music that lends itself to JJ’s creepy swagger: the jaunting, the creeping, and the jumping musicality of his limbs in the dark basement. Even his bowtie suit feels like he could’ve come over straight from his own funeral.

There’s actually a fun cameo in Butterscotch: the custodian sweeping the floor is Ryan Rael, who wrote the music on Jumpin’ Jacob, which is also what he’s listening to on his headphones.

8. Power Cycling. Speaking of age issues, “Butterscotch” stages a power struggle between young and old that’s kind of funny… at first. Does the power struggle have larger significance? What does the humor add to the dynamic between Bully and Old Man? The film’s ending makes the structure as a whole feel almost cyclical. Should viewers think that what happens has happened before and will happen again? Why or why not?

AD: To be honest, I never really considered the power struggle in the film. As for the ending, I’m a big fan of cyclical storytelling, and I love the idea that this Old Man has been sitting in this chair, gobbling people up, for so long that the staff just knows to leave him alone and give him a wide berth.

9. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

AD: Readers can find me and links to my current/upcoming work on my Instagram @goodsirfilms, as well as my website: alexanderdeeds.com. Thank you, Andrew, for these awesome and very thoughtful questions!

About the Filmmaker

Alexander Deeds grew up in Miami, FL, where he discovered filmmaking in high school. He made a feature-length horror film during his senior year, as well as countless shorts and music videos during his time at the University of New Mexico. After graduation, he moved to LA in 2015, where he spent several years editing movie trailers professionally. 2019 marked a return to filmmaking, and his two most recent shorts (“Jumpin’ Jacob” and “Butterscotch”) have played and won awards at some of the biggest genre festivals in the world. He is now excitedly working on the script for his new feature film.

Andrew’s Review of “Butterscotch”

Alexander Deeds’s “Butterscotch” packs an exceptionally satisfying punch not only because it delivers an unusual, unpredictable, and creepy scenario that unfolds between two compelling characters in a well-rendered world, but also because it does so in just a little more than seven minutes.

The first shot announces the film’s careful color coordination, showing hands in light blue gloves extending from darker blue sleeves. The hands rest on a light blue surface and frame a wrapped, butterscotch-yellow candy. The hands belong to a character named “Old Man” (Chad Sommer) in the credits; well-dressed in a blue outfit, he sits with the candy on his blanket-covered lap in a well-furnished room of a nursing home where a TV shows a black-and-white movie that, due to what appears to be catatonia, he looks toward but does not actually seem to see. The Old Man looks dignified yet pitiable.

The room’s paint and furniture offer more blues to coordinate with the Old Man’s apparel, and soon a child, credited as “Bully” (Reid Mcconville) enters wearing the same blue palette and a visitor tag. The Bully’s red hair, like the yellow candy, contrasts with all the blues: the primary colors of the costumes, set dressing, make-up, props, and cinematography are telling us something.

The story takes off when the Bully starts to, well, bully the Old Man. Using virtually no dialogue, the film uses the actors’ performances, nonverbal sounds, and music to build the relationship between them. The Bully makes faces at the Old Man, wads up and throws his nametag at him, approaches him, and sticks his tongue out at him, seeming to get no reaction at all. The Bully’s behavior is atrocious, repulsive, and it’s all the more cringeworthy because Megan Pham’s cinematography is generous with close-ups and extreme close-ups. He’s a brat who needs an adult to stop him from picking on a helpless old man.

The situation changes, however, and the characters get new dimensions when the Bully steals the Old Man’s candy. Loud crunching fills the soundtrack, and the boy returns to his chair opposite the Old Man. Suddenly, the Old Man looks toward him and seems to mimic his obnoxiousness. After that, things get scary.

Expert cutting in shot-reverse and other patterns (editing also by Alexander Deeds) builds tension as images convey that the Bully is not in the position of power he thought he was, and the Old Man is not what he initially seemed. The close camerawork shows fear in the boy’s eyes, and a sound equivalent—his heavy breathing—communicates fear overtaking his body. He might be obnoxious, but he’s just a kid, and he’s vulnerable. Music bolsters dread and assists with at least one jump scare as the situation becomes more twisted. Sound and image transform the initially placid blue world of the nursing home into a nightmare.

You have to see what happens for yourself, but it’s delightfully weird and pleasantly chilling, with an ending that is nothing shy of perfect. In both concept and execution, “Butterscotch” is an excellent film, a model for anyone who doubts that a stylish, unique, and thrilling horror story can come in a very small wrapper.