Interview with Author Sonora Taylor: Errant Roots (2025)

Insightful and compelling author Sonora Taylor takes us down into the Errant Roots of a family with horrific secrets and traditions that might make us feel like “going home” is anything but safe.

Errant Roots

Deirdre’s family tree was never something she thought much about. For 24 years it’s just been her and her mother. But when she accidentally gets pregnant, her mother insists they go back to their family roots. Now Deirdre is about to discover just what kind of sinister soil her family has sprouted from.

“Witchy, clever, thoughtful, and brilliant, Errant Roots pulls the reader into the story headfirst. You’ll need to read just one more chapter, and another, and another, until you’ve devoured the tale of Deirdre’s family and the secrets they keep. Sonora’s expert touch brings to life characters and a story that are a joy to read, with all those delicious little thrills of tension and fright.”

—Laurel Hightower, author of Crossroads and Below

“…the characters feel real, the dirt gets between your toes, and the emotions drive deep into the reader’s soul… a fantastic novella… that long-time fans of hers will be giddy about, and new readers will snap up her bibliography upon conclusion.”

—Steve Stred, author of When I Look At the Sky, All I See Are Stars

The Interview

1. Generational Trauma. Past interviewees such as Grace R. Reynolds have helped me understand “generational trauma” not only as a concept but as a current literary interest that Errant Roots might share. I think I can fairly claim that as Deirdre gets in touch with her “family roots,” she inherits a great deal of trauma. Even if the term isn’t one you’ve thought about, what do you think generational trauma is, and what inspired you to write about traumas passed down through family? One of the scarier aspects of Errant Roots is a looming threat that past traumas, and past generations, might be inescapable. Why is this threat so prominent, and why do you think, at least for some readers (like me), it’s so effective?

ST: While Deirdre definitely experiences trauma, I see it as less an inheritance and more her own unique experience based on the fact that she wasn’t raised to see what’s happening in her family as normal. I do believe that trauma is inherited, but in the case of the Crofts, they’re instead being taught to do terrible things to keep the traumatic instance that started it all buried. It’s a ritual meant to keep their family unit together, strong, unharmed by outside forces. Further, to Deirdre, everyone except her mother is an outside force; and yet she can’t help but feel a connection to her grandmother, aunts, and cousins even though she never met them before the events of the book. How does that protection look when the outside forces threatening the order are one’s own family?

2. The Persistence of Memory. As the novella’s description (above) indicates, Deirdre is 24 when she gets pregnant, and the number 24 ends up being very significant in the story. Did you draw on any specific lore when you came up with your numerical scheme? This interview’s readers might guess that the number has something to do with hours in the day and therefore time. What is Errant Roots’s perspective on time? Does Deirdre’s perception of time change by the end of the story? Closely related to time, or at least to the past, is memory, which the novella theorizes through one character’s voice: “‘When we die, we become memories… And sometimes those memories manifest into spirits.’” How are memories like ghosts, and what does their ghostliness do to our perception of time? In the world of Errant Roots, is there any practical difference between a remembered ancestor and the supernatural? Why or why not?

ST: I’m starting with the ghosts because I think it ties to the outside forces discussed above. The Crofts’ rituals involve sacrificing those that aren’t part of the bloodline. However, it never remains as simple as the original sacrifice. Each generation added a new rule to keep the family strong and, subconsciously, to keep the trauma they wish to avoid as far away as possible. It’s not enough to sacrifice someone, they now have to mutilate the victim’s body in a symbolic gesture to keep their ghost away from the family and forever cast out. The family’s rituals are a visual of their growing madness as they cling to the one traumatic death that started everything.

I think the number started and ended as a coincidence, and while there are things, like Harriet being born a day later than her sisters, that seem like something bigger is at play, I also believe the family began creating self-fulling prophecies once they noticed the pattern. Surely Harriet and Yvonne became more interested in finding a partner once they reached their 23rd birthday so as to maintain the line. You can’t predict pregnancy without medical intervention, though, so I can see why Harriet would think that maybe her distrust in the family was incorrect and tried to right it by bringing Deirdre to meet them.

3. Matriarchy. Powerful women rule Deirdre’s family: their tree is a matriarchy. They’re highly invested in family connectedness and horticultural symbolism for their matriarchal legacy. Is their organic power an alternative to patriarchy? Why or why not? At least some family members seem to be… hostile… toward men. Does matriarchal power require an adversarial relationship with men? Why or why not? I might go as far as to say that some family members see men as good for one thing only… to what extent is this attitude a deliberate reversal of all-too-common male sexism? The matriarchal power in Errant Roots might not turn out to be so admirable… is this form of power doomed to corruption? Why or why not?

ST: I believe the family’s matriarchy comes from the fact that it’s rooted in birthing cycles, and by the fact that this family is really good at having daughters. I see the family as less hostile and more indifferent towards men. With the exception of Deirdre and Sarah, they see them as a means to an end–in their case, maintaining the Daylight Branch and the strength of the family. Some of this could be emotional protection, since the ritual started after Deirdre’s distant ancestor Josephine lost her husband while she was pregnant. I think a lot of it, though, is being taught from a young age that this is what will happen, since the sacrifice of the seed (aka the man) is the oldest ritual still performed.

I totally think such power is doomed to corruption. I can tell you from my professional life that replacing a room full of men with a room full of women does not create instant harmony. Women can and will find ways to inflict violence on each other, be it physical or through microaggressions. This can also happen in families.

4. Purity of Blood. Deirdre’s family members are particularly concerned about the blood of their mothers (and their mothers’ mothers) flowing through their veins, and certain members seem particularly concerned about maintaining a kind of purity in a specific family line. Why is blood so important, and what’s the significance of some family members making even finer distinctions among their kin? I’ve read and written about other horror with “witchy” (to borrow Laurel Hightower’s word) groups that exercise brutal authoritarian power through an investment in elders and the practice of occult rituals, groups that evoke early twentieth-century fascism and perhaps other fascisms as well. Deirdre’s family, especially with its concerns about blood and purity, seems like such a group… do you think their model of power reflects at all on the contemporary rise of authoritarian power structures around the world? Is authoritarianism another generational trauma that has returned? Why or why not?

ST: I see the focus on blood as almost like a monarchic purity–all that matters to the Crofts are the relatives directly related by blood, aka the roots from the same tree. As history will tell you, this focus is doomed to failure, especially in terms of dominion. What’s interesting about the Crofts, though, is their lack of desire to extend that dominion beyond their own family. This is a very insular means of power, with outsiders only used as a means to an end. This is also what makes Deirdre so interesting when she enters the mix, because she was raised as an outsider, yet accepted by (most of) the family because she’s related by blood.

I think the Crofts relate to the contemporary rise of authoritarianism in the way they isolate themselves from anything that might disrupt their dogma. They reject doctors. Their children are homeschooled. They only interact with the police to buy silence and make sure no one comes looking for the people they sacrifice. They see this as the best way to maintain their strength and bond, and are very much takers when it comes to the outside world. This leads to an absolute power that, in the end, corrupts and destroys the very things its leaders claim they’re preserving.

5. Nurturing. Beyond concerns about the influences of blood, Deirdre worries about the influence of upbringing, wondering, for example, if her mother Harriet’s early exposure to her family has made returning to them after a 24-year separation, as well as other behaviors even more difficult to explain, into compulsions. To what extent is Errant Roots about the power of families, especially mothers, to nurture, power that can be used very well or very ill? Is the horticulture more important than the genetics? Why or why not, and what’s at stake in your answer? The family’s nurturing power helps inculcate newer members into its unusual belief system. To what extent does Deirdre’s family model how belief systems are passed on more generally? Do you think Errant Roots critiques religious indoctrination? Why or why not?

ST: The novella definitely explores the fact that even though Deirdre is related to everyone in the Croft household by blood, she is very much an outsider because of how her mother raised her. Harriet did not expose her to ritual sacrifice or the importance of maintaining what the Crofts call the Daylight Branch, a term for the center of their family tree rooted in the 24, 48, 72, etc. cycle of the women’s ages. She’s different from her cousins because she’s never had any of what she witnesses in the events of the novella presented to her as normal. Institutions that close themselves off like the Crofts are what allow their ideas to permeate and hold power over its members, whether they’re families or other people who’ve been indoctrinated. It’s why cults are so adamant about cutting off their members from outside influences.

I do, however, think that having a blood relation to someone gives them a unique, biological pull to an individual, even if they’re not close or have never met. It could be entirely cultural, or there could be something biological there; but I believe in it. Even though Deirdre doesn’t know of, or approve of, what the Crofts do, I still think she feels a certain bond with them–which makes the pain they cause her all the more devastating. The main difference, though, is that by being raised away from the core family unit, Deirdre has other options to explore when she wants to escape. I think one of the saddest moments in the book is when Sarah, one of the people who questions the practices, says she can’t, or won’t, leave the family behind because they’re all she has. Deirdre has more, and as such, has a chance at a happier ending, even when everything falls apart around her. I think a family that truly loves its members allows them to have this option, which is why I believe Harriet truly loved Deirdre, in spite of what happens in the story.

6. Pregnancy, Paranoia, and Conspiracy. Errant Roots is partly about a woman who gets pregnant and becomes increasingly paranoid as the people around her seem to have secrets and ulterior motives, perhaps even participating in a conspiracy, maybe even an occult conspiracy, related to her unborn child. In other words, it has more than good writing in common with Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby (1967) and many other narratives I might loosely describe as “pregnancy horror.” Why is pregnancy a good topic for suspense and horror? Why does it fit so well with feelings of paranoia and suspicions of conspiracy? Errant Roots raises the question of how far a mother would go for her child. How far, do you think? What forces are strong enough to make a mother betray her child?

ST: Well, at a base level, pregnancy is ripe for horror because you’re literally growing something inside of you. 🙂 One thing I find fascinating about pregnancy is how the minute a woman becomes pregnant, she’s suddenly not her own in the eyes of others. There are obvious extreme cases, like anti-choicers putting the existence of a fetus over the living woman’s own health and rights; but there are also less extreme instances like strangers touching a pregnant woman’s belly without asking, a pregnant woman being scolded for the choices she makes as not being good for the baby (like eating unpasteurized cheese or lifting a heavy box), and the expectation that the woman will give up everything–her job, her social life, her me time–to take care of the baby. It even begins before impregnation happens. I’m a ciswoman married to a man, and the moment we said “I do,” I joked that I was now under #WombWatch because people wondered when I’d be pregnant. Social media has only made this constant watching and awareness of being watched all the greater. Living in a panopticon of womb watchers is very ripe for horror, since, as with many experiences being a woman, you don’t have to add too much to what’s already real to make it a horror story.

I think in Harriet’s case, the only force strong enough to make her jeopardize Deirdre’s safety was wanting to return to her mother. I once read a sci-pop article that claimed of all the parent-child bonds, the strongest biologically was the bond between mother and daughter. This greatly influenced my story and helped me decide to make all of the characters mothers and daughters. Harriet still has hesitations when she decides to return, since she willingly severed the tie with her family to protect her unborn child. But she was also raised to think the Crofts were normal and that there was a greater power protecting them thanks to their rituals. She is the literal middle between Deirdre’s beliefs and Yvonne’s.

7. Get Out and Elevated Horror. Even before I reached the moment when Deirdre and her boyfriend Tom get the message telling them to “get out,” the set-up for Errant Roots had reminded me of the movie Get Out (2017), as your book also initially centers on a young couple who feel like fish out of water visiting an isolated family estate where family members seem to have secrets and might be plotting against them, particularly against the young man. Was this resonance conscious and/or deliberate? Either way, what do you make of the comparison? One commonality is that Get Out and Errant Roots both likely qualify as “elevated horror,” a term thrown around in the film world for the last decade or so to label horror stories that supposedly have greater-than-average attention to character, social issues, etc. How do you feel about the idea of “elevated horror?” However you feel, assuming you had to say something, what would you say elevates Errant Roots?

ST: I actually hadn’t considered Get Out, even though I very much enjoy that film. I was more directly influenced by Ready or Not, where a man brings his bride home to an isolated family estate to perform a ritual that requires her to die in order for the family to live. I often describe Errant Roots as Ready or Not meets The Witch. Regardless, I think the partner’s family home as danger, much like pregnancy, is ripe for horror because it stresses the difference between in-laws and blood relatives, even though a married couple is considered to be a family, and each spouse’s relatives are in turn considered the married-in person’s family as well. Yet in the case of an in-law or someone married in–someone who isn’t blood–the tenuousness of that bond is exposed the minute that tie is severed for any reason, be it divorce or someone’s parents not liking their child’s spouse. Get Out and Ready or Not show the danger that the in-law faces. I show this in Errant Roots, but I also examine the danger that even the blood relative faces, creating an incredibly dangerous situation where no one is safe in a space generally sold as the safest place to be: with one’s family.

8. Gothic Secrets. Largely thanks to the popular and critical success of Ann Radcliffe (1764 – 1823), the original Gothic novels and the horror traditions born from them often focus on long-hidden family secrets (secrets that usually involve mistreated women). Do you think of Errant Roots as Gothic in this historical sense? Why or why not? You include the Gothic trope (a favorite with Radcliffe and others) of the mysterious manuscript that provides the heroine with crucial information—why did you include the manuscript, and how does it enhance your story?

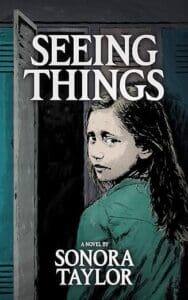

ST: I hadn’t considered the story to be Gothic when I wrote it–I considered it a blend of folk horror and cult horror–but I can also see how it’d be a contemporary Gothic story, like my previous book, Seeing Things. The main thing that separates them, and probably why I didn’t consider the Gothic elements, is the presence of the supernatural. Ghosts exist in Seeing Things. While I don’t want to dictate anyone’s take-aways from Errant Roots, I wrote it thinking there were no supernatural forces at play: everything was created and perpetuated by the human women in this family. One of the ways I show this is through the manuscript. Rituals and ideas are added by each generation of women, adjusting things to explain away the cracks in Josephine’s original plan. Like many radical beliefs, though, it takes an outsider like Deirdre to see those cracks for what they are.

9. Family. The series intro for Errant Roots, “Horticulture,” begins the volume with “Family matters matter more than most believe.” By the end of your book, I’m not sure how horrified by family I should be. What makes family matters matter? Is the way that family matters good, bad, or something else altogether? Do you think any family springs from untainted soil? Why or why not?

ST: Family is often characterized as a home base you can always return to when you need unconditional love and support. Many, many people throughout history will tell you this is not true to life. Families abuse each other. Parents kick children out of their homes. Siblings bully and torment each other. Relatives play favorites and pit their children against one another. Yet even with the growing acceptance of found families and accepting that someone being related to you doesn’t grant them access to you without boundaries, it’s still very, very hard to shake off the bond you feel with someone who is related to you by blood. I do think there’s some biology at play there, something in the blood that makes you feel connected to someone you’re otherwise not close to. This is why I think it’s so important to trust your instincts when something feels wrong about someone, even when–especially when–that someone is related to you.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

The best place to learn more about me is on my website: https://sonorawrites.com.

I am also on Bluesky and Instagram.

About the Author

Sonora Taylor (she/her) is the award-winning author of several books and short stories. Her books include Someone to Share My Nightmares: Stories, Seeing Things, Little Paranoias: Stories, Without Condition, The Crow’s Gift and Other Tales, and Wither and Other Stories. She also co-edited Diet Riot: A Fatterpunk Anthology with Nico Bell. Her short stories have been published by Rooster Republic Press, PseudoPod, Kandisha Press, Camden Park Press, Cemetery Gates Media, Tales to Terrify, Sirens Call Publications, Ghost Orchid Press, and others.

Her short stories and books frequently appear on “Best of the Year” lists. In 2020, she won two Ladies of Horror Fiction Awards: one for Best Novel (Without Condition) and one for Best Short Story Collection (Little Paranoias: Stories). In 2022, her short story, “Eat Your Colors,” was selected by Tenebrous Press to appear in Brave New Weird: The Best New Weird Horror Vol. 1. In 2024, her nonfiction essay, “Anything But Cooking, Please,” was a Top 15 finalist in Roxane Gay’s Audacious Book Club essay contest.

For two years, she co-managed Fright Girl Summer, an online book festival highlighting marginalized authors, with V. Castro. She is an active member of the Horror Writers Association and serves on the board of directors of Scares That Care.

Her latest short story collection, Recreational Panic, is now available from Cemetery Gates Media.

She lives in Arlington, Virginia, with her husband and a rescue dog.