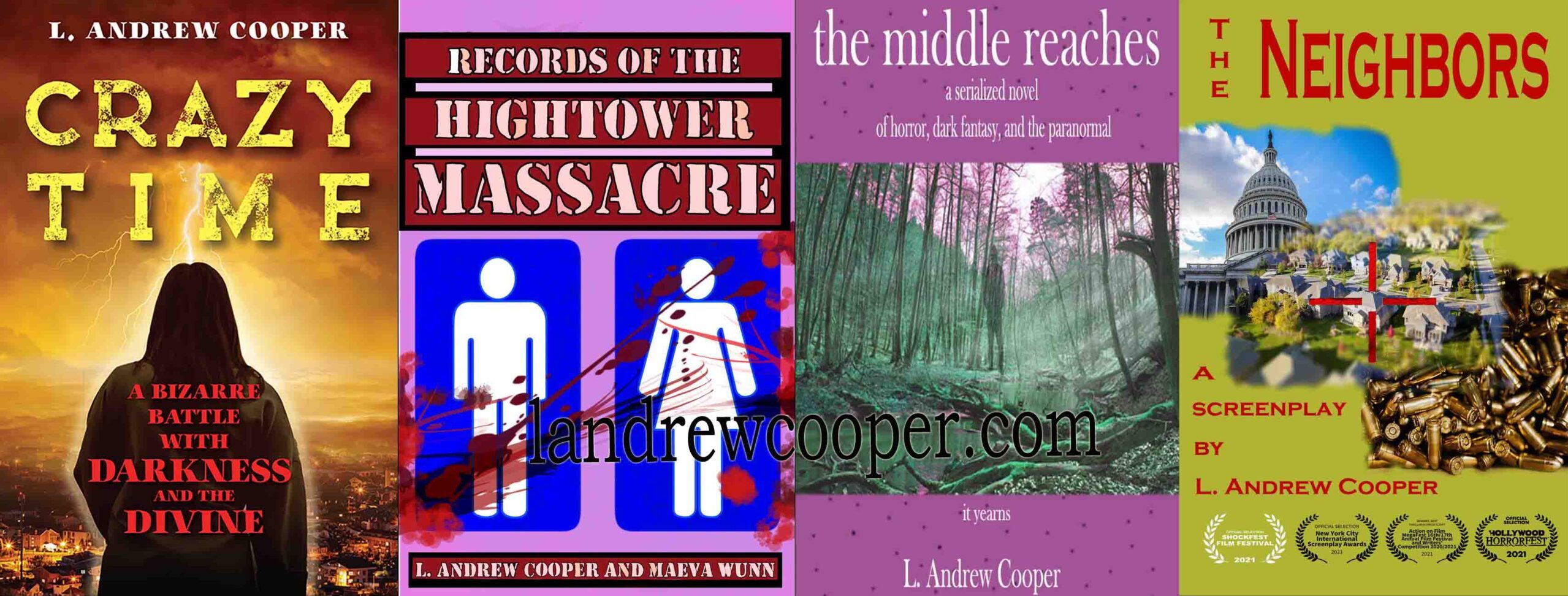

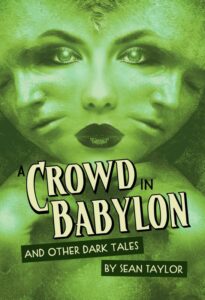

Interview with Author Sean Taylor: A Crowd in Babylon (2023)

Sean Taylor, a widely published author of comics, short stories, and novels and a general purveyor of things strange and scary, is here to discuss his new collection of dark short stories, A Crowd in Babylon.

A Crowd in Babylon and Other Dark Tales

Seventeen tales of Southern horror, dark fantasy, and weird adventure inspired as much by Flannery O’ Connor, Eudora Welty, and Shirley Jackson as by F. Marion Crawford, Stephen King, and Ray Bradbury, A Crowd in Babylon takes you from the chilling underside of the urban landscape and the homegrown terrors of rural life to the hidden frights that lie beneath suburban smiles.

- A zombie whose work funds the lifestyle of her cheating husband

- A musician who learns that true art requires irretrievable loss

- A Cherokee brave who must face the monsters from his people’s legends

- A time-traveling widow nursing a violent and deadly grudge

- A woman who needs four-footed help to teach her grandchild to grieve

- A young writer obsessed with a dead actress

- An immigrant haunted by the vengeful ghosts of children

- And ten other creepy tales!

Even though there’s already a crowd in Babylon, one more soul is always welcome. Prepare to meet the ghosts, creatures, and nightmares of people and places both new and familiar.

The Interview

(1) Babylon and the Crowd. A zombie, a musician, a Cherokee brave… your descriptions are character-driven and diverse. To what extent do characters and specific points of view drive your stories? You’ve got some wild characters as well as some wild storylines—would you say you prioritize either character or plot? If not, if you had to choose one, what would you say?

ST: I’m one of the nutjobs who still believes that character is king (or queen, or even court jester when that role is most important for a functioning kingdom). I’ll sacrifice plot for character all day long the same way Shakespeare would sacrifice logical plotting for a good sex pun.

There is no story in my mind without strong, compelling characters. If I don’t care about the characters I’m reading, then why the hell would I ever care about the plot that happens to them?

I love my wild characters. They’re wild, yes, but I hope readers will also find they’re normal too. There’s the publisher who just wants a successful series of books even if his wife is writing them as a resurrected zombie. There’s the grandmother who is so busy mourning her daughter that it takes the help of a dead family pet to help her grandson learn to grieve. So, yeah, on the surface, there’s a lot of wildness in the characters I choose, but I also try to ground them in the real and the true that we can all find in common.

(2) Babylonian Fantasies. Some of these stories take the perspectives of characters living through, or acting out, fantasies with dark outcomes. Where do you get material for character psychology? How does your own fantasy life relate to the fantasy lives of your characters?

ST: Thank you, Dr. Freud. I’m so glad you asked. (Ha!)

My imagination is fairly macabre and there’s no hiding it. When you couple that with my belief that human beings just don’t learn from good times and happy endings, but instead only learn when they face hardship or pain or tragedy, it makes me sound like a real downer of a person. I’m not a pessimist actually, but I do believe it takes those things to make us stop and pay attention. Yeah, I know it’s not the happy rainbows and unicorns outlook, but I’ve seen it happen over and over again in both my life and the lives of so many others that I can’t help but claim it as a truth for me.

(3) Crowds of Genres. While “horror” describes some of the tales, you’re right to emphasize “dark,” as you bring in sci-fi and other genre conventions as your stories wend along their dark ways. How do you think about genre when you write? Do you set out to craft stories in particular genres, set out to blend genres, let the stories tell you what conventions they should involve, and/or deal with category questions in other ways?

ST: My favorite writers tend to blend genres in their work. For example, if I look for Neil Gaiman, do I go to fantasy or horror or literature? For Ray Bradbury, are his collections sci-fi stories, horror stories, coming-of-age stories, or shades of all these? And if I want Vonnegut, do I go to literature or to sci-fi? C.S. Lewis wrote children’s fantasy and adult sci-fi and theological nonfiction, and he blended those in each of his books to some degree.

All that to say, I think the blending of genre tropes and styles are crucial, and yes, I fully intend to blend them as I write—from the get-go.

(4) Southern Babylon. What makes some of these stories “Southern” horror?

ST: To me, Southern is less a geographic place and more a collection of ways of thinking about community and where we fit into it. Southern features a lot of public politeness with private backstabbing. Southern features a lot of “support” that is really just thinly veiled judgment in everything from a haircut to chosen employment. Southern is the drive to remain part of that community despite those kinds of behaviors. After all, it may not be the best place to be, but it is MY place. I think that’s something I learned to put into words from reading Flannery O’Connor, particularly the novel Wise Blood or the story “A Good Man Is Hard To Find.” I think that on some level, all real Southerners live with the knowledge we’d all be damn good people if we just had someone there to shoot us every minute of our lives.

My characters live within that conflict and usually do so without consequence until the horrific event happens to make them confront it. (The stories don’t get good until my old ladies run into the Misfit, so to speak.) [Note from Andrew: If you don’t know what Sean is talking about, I give a brief summary of “A Good Man is Hard to Find” in this post.]

(5) Crowded Theaters. I know from your stories as well as from previous encounters—such as the compelling discussions you’ve often hosted on social media—that the movies play a big role in your stories and style and that you’re very well-informed about cinema history. What movies (and actors and other aspects of cinema) had the biggest impact on A Crowd in Babylon? Where and how will readers see the influences?

ST: Hands done, for this collection, it’s classic ghost stories with their slow build and their grinding tension, and also the Hammer films of the sixties. Both of these kinds of films tended to focus on the characters rather than the monsters—or they treated the monster/ghost as a character, not just the Satanus Ex Machina (I needed an opposite for the Deus Ex Machina, and I like it, so I’ll keep using it).

And to make an even stronger connection to film, in the story “And So She Asked Again,” I directly bring in one of the famous Hammer actresses, the always enchanting Barbara Steele.

There’s also a pretty strong influence of the more modern, surrealistic story (almost going so far as to become Magical Realism), where ordinary people find themselves in supernatural situations that feel as “every day” as they do “out of the ordinary.” I think I picked that up from films like Neon Demon and Last Night at Soho (and older Italian horror like Phenomena and Suspiria).

And “Death with a Glint of Bronze” is practically a steampunk Giallo, so there’s that, but it’s clearly an outlier in this book.

(6) Babylonian Influences. While we’re on the subject, your description of the book cites six of your prose-writing influences. Would you choose a couple and provide specific (spoiler-free) examples of where readers will hear their echoes within A Crowd in Babylon?

ST: Sure. Again, those influences are Shirley Jackson, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor, Ray Bradbury, Stephen King, and F. Marion Crawford. I mentioned both Welty and O’Connor earlier, but I’d love to point out the influence of the others.

Shirley Jackson redefined what a ghost story could be for me. The ghosts of Hill House are both those warping the bedroom doors and those that live inside Nell. This changed the way I saw ghost stories. Suddenly the creepy stuff on the outside had to play off the creepy stuff on the inside to create a far more convincing level of horror. I think the stories “To Gnaw the Bones of Wolf-Mother” and “The Ghosts of Children” probably best show off that kind of influence.

Ray Bradbury seamlessly blended horror and fantasy and sci-fi with tales like “The Veldt” and several stories from The Martian Chronicles. That marriage of science and scary shows most in stories such as “And So She Asked Again,” which is based on String Theory, and in my approach to zombie stories, as seen in “Art Imitates Death” and “Posthumous.”

King, well, King is king, so to speak, and any horror writer who tries to pretend he’s not an influence is just lying to you. He’s influencing you in ways you probably don’t even know. I think for me, though, King is the master of a sort of pop-culture-stylized Magical Realism. It’s amazing to me how his characters can so easily deal with bizarre things like Indian burial grounds and living cars and haunted stationary bikes, etc. That kind of meek acceptance is all over my stuff, and I see it already as a strong part of my next collection of horror stories, too.

Crawford is a forgotten gem, I think, known only to the most die-hard classic horror fans. Crawford’s knack for getting into the psyche of his characters is the creepiest part of his stories. The ghost children in “The Face of the Yuan Gui” and the almost normalness of the bar in “The Color of the Blues” show the strongest Crawford influence because we see what the exposure to the weirdness does to the person experiencing it.

(7) Crowded Reasoning. You commented in our correspondence, “the horror of the why is far creepier than the horror of the what happened.” In your story “The Ghosts of Children,” one character asks another, “Why are you doing this?” before the “this,” the what that’s happening, is entirely clear. What effects are you hoping to achieve by withholding this information? Would you describe withholding crucial journalistic information (the five W’s and an H) as a central aspect of your style for creating horror and suspense? Whether or not this sort of withholding is one of them, what would you claim as major tools in your writer’s toolbox?

ST: My favorite horror stories (both on film and in prose) have a dose of mystery. Look no further than Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” and The Haunting of Hill House. Not only that, but it’s that mystery that make the 60s and 70s Giallo thrillers work, and not only those but the genre films they influenced, such as Friday the 13th.

So, of course, I want to include a little bit of mystery in my stories. I think withholding some of that helps maintain suspense and stretches the nerves for tension. Plus, I also write a lot of Noir/Hard-Boiled pulp stories, and the mystery that accompanies those tends to seep into my other genre work.

That statement you mentioned, “the horror of the why is far creepier than the horror of the what happened,” that’s pretty foundational for me when I write. Why a person chooses to live in a house where they’re obligated to keep a bottled, dead squirrel in the basement is far more interesting than what happens when the bottle is moved. Why a person embraces the up-close killing with a gauntlet over a blade or a pistol is the really creepy part, even moreso than the description of the killing itself.

As for other tools, I love to use the sounds of words to make guttural stops and soft letter sounds when I want readers to move quickly. The ‘k’ and ‘g’ and ‘b’ and ‘d’ sounds are the best for auditory knife stabs. Used with intentionality, they are the shower scene stabs you can use in your written work. They force a reader to stop, if only for a moment.

I wrote about this in a tutorial on my blog and I’ll repost that bit here because it relates:

Use sounds that bother the reader, not just the characters. You can make up words that sound like stuff. The official literary term for this is onomatopoeia, and it works because it plays games with the reader’s ear, whether they hear the sounds spoken aloud or not.

For example, in my steampunk horror tale “Death with a Glint of Bronze,” I hit the reader right off the bat with the “crick-cracking of the neck bone where it attaches to the top of the spine.” But the following sentence continues the idea, simply by using sounds that create a stop and reflow, like restricted breathing might sound: “Then there is the delicious constriction as the breath slowly ceases its movement through the windpipe.”

(8) Details in Babylon. Your stories include magnificent details, specific types of knots, antique furniture, scientific theories that aren’t common knowledge, and more. Do you do a lot of research? Are you just extremely knowledgeable? Where do all the details come from, and what reactions do you hope readers will have?

ST: I wish I was naturally knowledgeable. But sadly, I have to dig for every bit and bob I use to add color to my work. But I won’t deny it: research is the fun part. I drop TK or blank lines (in bold, of course, to find later) all over my stories so I can research the things I didn’t realize I’d need to know about. I learned TK from my time on various magazine and newspaper staffs. I have learned so many cool things from this, like you mentioned, from antiques and scientific theories to the process of artificially inseminating a dairy cow and male and female fashion of the 1930s.

As for finding the details, I always try to find the original source behind the easy-to-find source. The last thing I want is for an expert to accuse me of not putting in the work to get the details right.

(9) Babylonian Truth. Your author bio (below) describes you as a writer of lies, but I’d be shocked if you weren’t aware of some truth-telling in your tales. What truths do you tell?

ST: At the risk of sounding like one of the literary snobs that make such great, bloated targets, I like to think that I tell lies to get to the greater truths. I know that as an English teacher, I’ve learned more about myself and the way I can be by observing the fictional lives of the characters I read about. I’d like to think that Edna Pontellier and Ethan Frome helped me not hide my real needs and desires. I’d like to think that seeing Captain Nemo’s unrelenting crusade helps me avoid such singlemindedness in my life. Those are the human truths that I think fictional stories can best present. I also believe that fiction is a fantastic place to discuss all those topics we’re taught to avoid in public and at the table during Thanksgiving—things like religion, spirituality, politics, gender issues, equality, racial issues, etc.

(10) Access! How can readers learn more about you and purchase your works (please provide any links, social media handles, etc. you want to share)?

ST: My website: www.thetaylorverse.com

My writing blog: www.badgirlsgoodguys.com

Twitter/Facebook/Pinterest: @seanhtaylor

Instagram/Threads: @seanhtaylor1111

About the Author

Sean Taylor is an award-winning writer of stories. He grew up telling lies, and he got pretty good at it, so now he writes them into full-blown adventures for comic books, graphic novels, magazines, book anthologies and novels. He makes stuff up for money, and he writes it down for fun. He’s a lucky fellow that way.

He’s best known for his work on the best-selling Gene Simmons Dominatrix comic book series from IDW Publishing and Simmons Comics Group. He has also written comics for TV properties such as the top-rated Oxygen Network series The Bad Girls Club. His other forays into fiction include such realms as steampunk, pulp, young adult, fantasy, superheroes, sci-fi, and even samurai frogs on horseback (seriously, don’t laugh). However, his favorite contribution to the world will be as the writer/editor who invented the genre and coined the term “Hookerpunk.”

For more information (and mug shots) visit www.thetaylorverse.com and his writer’s blog at www.badgirlsgoodguys.com.