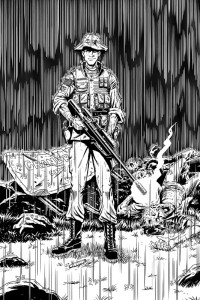

Peter Welmerink’s Transport, Hunt for the Fallen: Taking Zombie Fantasy to the Next Level (2015)

Book Synopsis for Hunt for the Fallen:

Captain Jacob Billet

Journal Entry – Sunday April 5, 2026

It’s raining, it’s pouring, the undead are roaring…

Amassed at the UCRA east end enclosure, the dead strain the fence line while soldiers keep watchful eyes, the survivors on the opposite side of the rising river about to lose their minds.

It’s a crazy time: nonstop precipitation; everyone’s up in arms; paranoid city council members with an asshat City Treasurer. Water, water everywhere. Zees dropping into the churning drink. Troops afraid of being stitched up and thrown back into the fray as Zombie Troopers. Tank commanders getting itchy to head out on their own after drug-laden shamblers. Reganshire insurgents trying to extract our west side civvies for some unknown reason, possibly pushing the city into taking heavy-handed action against them.

Then there’s some black-haired dead dude staring at me through the fence, grinning like he’s off his meds.

And I thought Lettner was a headache.

All this sh*t might give me a heart attack.

I reviewed Welmerink’s Transport in June 2014, so when offered a review copy of the follow-up, Transport: Hunt for the Fallen, I happily accepted. Welmerink’s world gives the zombie subgenre a much-needed facelift, keeping the fundamental edges of violence and desperation but refreshing the conditions for storytelling. In brief, the Transport series takes place near Grand Rapids, Michigan, a city re-established years after a zombie plague has brought on an apocalypse, and charts the adventures of people trying to navigate a newly emerging world (dis)order in the city and outlying areas.

By skipping over the familiar—the initial horror of figuring out what’s going on, of watching the population’s rapid decline, and especially of figuring out the relationship between the living and the dead (they’re us!)—Welmerink creates an opportunity to use the “Zees” and human survivors in unfamiliar scenarios, adventuring in a world rebuilding itself rather than a world falling apart. Without acknowledging the existence of other zombie fictions, the writing admits that you might know them and benefits from the admission: the existence of zombies in the fictional world of Captain Jacob Billet and the crew of his transport vehicle the Huron is just as quotidian as the existence of zombies on TV and in the movies. Welmerink doesn’t need the monsters to be novel and in fact benefits from their familiarity. The more you know about typical zombies, the more you can pay attention to Welmerink’s innovations (so plentiful that Book 2, like its predecessor, has a glossary).

One of Welmerink’s innovations, present in the first volume but more crucial in the second, is the role the undead have assumed in the post-apocalyptic society. In what reads to me as pervasive satire on extremes of political correctness, even “zombie” seems like a bad word in the polite society that has preserved and domesticated hordes of the walking dead. The zombies are “undead civilians” kept in Urban Civilian Retention Areas (UCRAs), retained and even revered as the loved ones of survivors who just had the misfortune of rising from death with a hunger for human flesh. Nevermind that if a UCRA has a problem, and these civilians get loose, they readily dismember and devour the same people who maintain them on diets of doped gore rations. The more disgusting the creatures, the more defense they get from the government and civilians, much to the chagrin of Billet and his military crew, who find their hands tied again and again because saving the living by shooting the dead courts political blowback that’s more of a headache than the Zees themselves. The city’s inhabitants, relatively safe in their enclosed environment with the apocalypse a fading memory, don’t see the monsters as a threat. They hardly see them at all, but instead see their own wishful thinking projected on ambulatory decay. This satire might be problematic if the zombie masses had—as they do in many other stories—a close association with a particular type of person or group, but they don’t. The satire works because without attacking any specific political class or viewpoint, it shows that, like cockroaches, hypocritical denial and refusal to face unpleasant physical circumstances will likely survive the fall of civilization and be with us as long as there’s an “us” to be with.

A less gleeful dimension of this commentary appears in the division between military and civilian, with the civilian getting far more respect, a respect painfully ironic because the word “civilian” is the most common and proper term for undead flesh-eater. Jake Billet, considering that the government expects soldiers to keep soldiering even after death, “doesn’t like what he sees and doesn’t like the implications… For the military, if a soldier isn’t blown to little red bits, it is experimentation and the life of a ZT, zombie trooper… [whereas] undead neighbor[s] find themselves protected and fed until they fall to the elements or rot to nothing and dissolve to a gooey paste” (68). That rotting corpses rank higher in the social schema than self-sacrificing soldiers is a fact of daily life about which Billet can only brood. Soldiers are tools, dehumanized, used as much as their bodies will tolerate (and more); civilians, even when they are inhuman, receive the best possible human comforts—so what if they can’t enjoy the advantages? Read against the backdrop of a real-life American culture that has waged constant wars in the twenty-first century while the ruling elite have gotten richer and richer, this hierarchy resonates powerfully, implicitly calling not just for a rethinking of the new society in Transport’s pages but of the society it has replaced.

This rethinking, though, is almost all implied, as Welmerink is too busy delivering a fast-paced action yarn to get bogged down in political rumination. A continuation of the adventure begun in Transport, Transport: Hunt for the Fallen is also episodic, hurling Billet and crew into a series of conflicts that, as before, ultimately end up on the road, this time hunting for and retrieving various types of “fallen” folk, including escaped undead civilians for whom the living military must risk life and limb (and limbs and other bits do fly). A lot of the book’s fun, for me at least, lies in not knowing where the story will go next—the serial, episodic structure of events and the unfamiliarity of the world Welmerink is building keeps at least one eye blind to what’s ahead—so I won’t say more about the plot. I will say, though, that each episode escalates, and the best part of the book is the final third, in which the storytelling concentrates on hard-hitting battle sequences. A spoiler-free sample:

“A gurgling snarl brings the gunner back to the forefront as the big zomb swipes at him with a tree trunk thick arm. Necrotic flesh flaps like loose strips of dead bark” (122).

Vivid present-tense narration and unabashedly visceral description make these scenes intense and enjoyable. The ending has chilling surprises, too, and the final image includes some of the best writing in the series so far.

I have some quibbles, of course. Like the first book, the second could use more editing, but more important, I might like to see the glossary expanded further to include key characters and locations as well as more of Welmerink’s cool terminology—with more than a year between my readings of books one and two, I needed some cross-referencing. And while I like the unpredictability of the story’s structure, which builds up to the thrilling fight scenes toward the end, I might like to see more heavy artillery fighting and a little less build (mostly because the action scenes are the book’s best).

Quibbles aside, I recommendHunt for the Fallen to anyone who has started the series and the series to anyone who enjoys zombie stories or just stories rich in imagination that pack a hard-action punch. Transport’s gritty characters, visceral description, and fresh vision of the post-apocalypse are worth taking for a ride.

About the author: Peter Welmerink was born and raised on the west side of pre-apocalyptic Grand Rapids, Michigan. He writes Fantasy, Military SciFi, and other wanderings into action-adventure. His work has been published in ye olde wood pulp print and electronic-online publications. He is the co-author of the Viking berserker novel, BEDLAM UNLEASHED, written with Steven Shrewsbury. TRANSPORT is his first solo novel venture. He is married with a small barbarian tribe of three boys. Find out more about his works and upcoming projects at: www.peterwelmerink.com