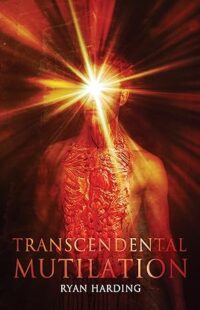

Hardcore horror writer and pioneer of body horror in print Ryan Harding is here to discuss his new collection of short stories, Transcendental Mutilation, a collection of tales interconnected on several levels.

Transcendental Mutilation

SIGILS INCISED, A COMMUNION WITH THE BLADE. A trio of young people stranded on an uncharted island discovers its sickening secrets. A man contracts a degenerative disease through a webcam encounter. An office worker follows the object of his affection into a mysterious club where life, death, and anatomy have no limits. A reforming necrophiliac struggles to maintain the illusion of normalcy in a new relationship. A woman awakens with other captives in the basement of a madman using them to attract impossible prey.

UNLOCK THE GATES OF FLESH, WORLDS WITHIN FLAYED. A decade after the infamous Genital Grinder, Ryan Harding returns with ten more stories, collected for the first time— including the Splatterpunk Award-winning tales “The Seacretor” and “Angelbait”— which plunder the depths of depravity and obsession, yielding offenses and transformations of the flesh never before seen or carved. His first solo work in years dissects its themes and characters alike in a sublime autopsy worthy of the hardcore horror pantheon. Even the vomitorium has its philosophy, and the keys to revelation are all serrated.

EVERY JOURNEY BEGINS WITH A SINGLE SLICE… TRANSCENDENTAL MUTILATION

The Interview

1. Transcendental Details. In your “Prelude to Repulsion” at the beginning of Transcendental Mutilation, you mention that stories in the book link to each other as well as to your other works, and indeed, references to Sarah Putnam, Geisha Hammond, the Woodsman, and Agent Orange recur, places such as Morgan, Sandalwood, and Iona come up repeatedly, and the character Kendall appears more than once. Tell us more about your interconnected universe (or, if it’s a multiverse, your multiverse). Which details tend to reappear and why? What do they add to the stories and to readers’ experiences? Without giving too much away, what elements from Transcendental Mutilation might readers expect to see again?

RH: This is something I started in Genital Grinder. That interconnectedness resonated with me in a collection like Bret Easton Ellis’s The Informers. It adds another layer, turning it into its own world with a recurring cast, hopefully investing readers that much more in what’s going on. As stories like “Final Indications” (in GG) and “Last Time at Thanksgiving” (in Transcendental Mutilation) threaten something more apocalyptic, I suppose they function more like resets, although there are recurring threads from GG in TM, and characters and ideas from TM could also manifest in other stories or books one day. The Woodsman is something I’ve thought about revisiting, for instance, and I keep threatening to continue the misadventures of Von and Greg from GG.

2. Transitory Bodies. Aside from his involvement in the plot of “Orificially Compromised,” who is “Dr. Braedon Obrist,” and what is “Transitory Bodies?” Why have you added a quotation from this work to each tale? Do the quotations point toward a larger, coherent philosophy behind Transcendental Mutilation? If so, would you please—in brief—explain the core of that philosophy?

RH: Dr. Braedon Obrist is sort of like TM’s answer to Brian O’Blivion from Videodrome—a philosopher for a world influenced by technology in ways both physical and metaphysical. You only get so much insight into his views in “Orifically Compromised,” so I thought it would be interesting to use excerpts from his Transitory Bodies book as epigraphs. I imagine TB to be a collection of essays where he explores existential questions proposed by the changing nature of our psyches with technology and the imminent threat of InterphaZ. I just sat down one day and wrote them all, and I liked how they came out. The excerpts obliquely lay out themes for each story. If there is a coherent philosophy, it is the idea that the modern world is altering us in ways we haven’t seen before, connecting us more but also enhancing our individual alienation. We’re patient zeros of a technological and resulting metaphysical virus. The characters in TM are often transformed by that virus or willing to alter themselves, sometimes as an escape, other times as an assimilation. In stories where technology fails, there tends to be something older and darker lurking.

3. Long Live…. “InterphaZ,” mentioned in several stories, especially “Orificially Compromised,” seems right at home with David Cronenberg’s Videodrome and eXistenZ, and since you contributed “Orificially Compromised” to the collection The New Flesh: A Literary Tribute to David Cronenberg, I’m guessing that’s no coincidence (you also praise Cronenberg extensively in your postscript to Transcendental Mutilation). What is InterphaZ, and how specifically does it relate to or reflect on Cronenberg’s creations? More broadly, how have Cronenberg and other filmmakers influenced your writing? What, if anything, is cinematic about your style?

RH: InterphaZ is a mega corporation furthering technology and the subtle (and not so subtle) mutation of its customers. I think it’s a more cynical interpretation of some of the organizations from Cronenberg’s films, slowly recreating the world in its preferred image. In “Orificially Compromised,” doctors must be approved for any treatment pertaining to an InterphaZ product. That only seems barely absurd these days. They also play a role in mind control technology in a novella I wrote called The Profile, part of the Call Me Hoop anthology. I love David Cronenberg, and his body horror films had a major impact on me. It’s something we all have to confront if we live long enough. Our bodies will change and ultimately fail us. It’s a more visceral metaphor for the dying process. I believe graphic horror is especially the province of horror films, where gore in splatter movies like Dawn of the Dead preceded the works of Clive Barker and the Splatterpunks in the 80s. Extreme horror is often like elaborate special FX work, e.g., the exploding head in Scanners, the transformations in Videodrome, The Thing, etc., and the carnage of Italian horror like Fulci, Argento, etc.I try to be as descriptive as I can with those sequences, although ideally they will feel more like something readers are experiencing than merely witnessing.

4. Genital Mutilation. The title of your previous collection, Genital Grinder, seems to warn of this motif: you write about violent damage to or transformation of genitalia in quite a few tales in Transcendental Mutilation. What’s your attraction to this region of repulsion? What do you think attracts readers to genital chaos (I squirmed but couldn’t stop reading)? Except when characters enjoy it (and they usually don’t), do you see genital mutilations as punishments for wayward desires? Why or why not?

RH: That was something tabooer when I began writing my hardcore stories. I mentioned how splatter was prevalent in horror movies, but anything genital related was scarce compared to eviscerations or head explosions. I would say disembowelment was the ultimate splatter effect (anything involving genitals was quick to hit the cutting room floor to avoid an X rating), but the rarity and intimacy of a scene like the castration in Make Them Die Slowly could make an indelible impression, too. In 1999, I read Edward Lee and John Pelan’s Shifters, which includes this excruciating moment with a woman and a pizza cutter. I planned to read at the Gross-Out contest at World Horror Con, and that book (as well as some of the other hardcore epics of the day by Edward Lee) awakened me to just how far I would have to go to really stand out. You couldn’t just use splatter horror for a template—you had to go beyond what even movies would show. That was much of the impetus, particularly in trying to create that feeling of shock some of us felt watching a movie like Make Them Die Slowly or Joe D’Amato’s Buried Alive on video back in the day. Something that went far beyond the Freddy and Jason fare that had lapsed into greatly diminishing returns. Since even mainstream horror goes so much farther now, it’s harder to conjure the feeling of witnessing something you weren’t meant to, like those Euro horror atrocities in the video age or the imagery and lyrics of the Chris Barnes era of Cannibal Corpse. Do I see that genital violence as a punishment? That element is sometimes there, but not always. Sometimes it’s just the random cruelty of fate. It’s also a part of you that is usually hidden from the world, so there’s an added element of violation to it, as well as the awareness of how sensitive those areas are.

5. Mutilation Pro Quo. Along lines similar to the last question, some of the violence in your stories seems rooted in payback, particularly payback for men who have sexually objectified or harassed women. Even though in the postscript you say you’re “not big on moralizing,” is cosmic justice ever at work? Do you see yourself indulging a feminist—or at least anti-misogynist—streak? Why or why not? How do you think your own treatments of gender relations compare with gender relations in hardcore horror more generally?

RH: It is a little funny to get a question like that, because after Genital Grinder, many would swear I must be an avowed woman hater. I feel like there was equal opportunity eradication in that collection, but there are prevalent misogynistic attitudes in it for sure, since some of the stories are about killers, and I was influenced by reading a lot of true crime back then. I wasn’t trying to redress a balance in Transcendental Mutilation, so much as just exploring the consciousness of the kind of person who would be amenable to revenge porn (“Threesome”) or online indecent exposure (“Junk”). I see these stories in particular as part of the EC Comics end of the spectrum, where somebody receives an ironic comeuppance, so I suppose that’s a sort of cosmic justice at play. As for my treatments of gender relations, though, like you alluded, I try to avoid moralizing. I don’t want to come off as didactic. I’m trying to present everything as part of a story, not a sermon. I don’t know that it’s necessarily a hardcore horror staple to go the other way with it, but it seems like a broader tendency in books and film in general now, to their detriment. I want my work to stand apart from that.

6. Transcendental (Sub)genres. While most of the tales have what we might fairly call supernatural components, some come closer to more familiar supernatural subgenres, such as tales interested in the modern mythic, (sub)urban and internet lore—“Down There” and “Junk,” perhaps “Threesome”—and stories of the occult/religious—“Angelbait” and “Temple of Amduscias.” Did you set out to write out in these subgenres, or did you follow your muse and end up there? How do you feel about these categories and this sort of categorization?

RH: “Down There” just sort of happened. I owed a story to Matt Shaw’s Masters of Horror anthology, and there was a news item about the girls in Michigan who stabbed another friend as a sacrifice to the Slender Man. I started thinking about how ominous the woods seemed when I was a kid, riding past them on the school bus, and how eerie the woods still seem. I started from that fear and “Down There” just revealed itself to me day after day. That doesn’t often happen for me with short stories. I usually have to know where they’re going in advance, or they don’t go anywhere. With “Angelbait,” I was reading about some of the sickening things saints had purportedly done, and how an angel was said to have appeared at one martyrdom. I thought, “What if that was someone’s goal?” Everything fell into place with that. “Temple” was intended for a King Diamond tribute anthology. Jarod Barbee of Death’s Head Press reiterated to me that he wanted something a lot more reliant on atmosphere, so I needed a place that was quiet and isolated. A lot of King Diamond/Mercyful Fate music has occult themes, too, which was another important element, although what unlocked that story for me finally was just figuring out Olivia, the protagonist.

7. Mutilation for Heavenly Purposes. Speaking of “Angelbait,” it is one of the two Splatterpunk Award winners in this collection, and it’s powerful, reminding me of two of my favorite filmic works of extreme horror, John Carpenter’s Cigarette Burns (from the anthology TV series Masters of Horror) and Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs (one of my favorite films of all time). Be as vague as you need to be to avoid spoilers: is what this story says about the nature of transcendence, however good or bad, a view of transcendence you mean to profess? Why or why not? Do you think that perhaps, over the years, horror has transitioned from asking “Why is there evil in the world?” to asking “Does good even exist?” Why or why not?

RH: I loved Martyrs, too! I think it’s the rare kind of movie able to resurrect that old feeling of shock over what you are seeing, with a lingering aftermath of disturbance. I’m sure I had it in mind writing “Angelbait,” and maybe subconsciously Cigarette Burns, too. I think a good summary of it thematically is a Satyricon lyric: “Damned or saved, how could we ever know?” In the world of this story, being chosen is a curse, and divine intervention comes with its own horror. Likewise, I think transcendence elsewhere in the collection (“Divine Red”) is something positive, however deranged. In “Orificially Compromised,” it’s more ambiguous… how much of Porter’s euphoria is even his own at the end? Transcendental Mutilation to me means the willingness to ascend above the inherent banality of existence, with characters willing to mutilate their lives, themselves, and/or others in pursuit of whatever higher meaning they aspire to. That’s an interesting question about horror and the existence of good. There does seem to be more cynicism now. Even someone like David Lynch who clearly believes in diametrically opposed good and evil can really drag you through the dark. Perhaps there is this decaying belief in everything—government, media, law, religion, etc., and it manifests in more creative expressions of hopelessness and pessimism.

8. Transcendental (Sub)genres II. In this collection’s other Splatterpunk Award winner, “The Seacretor,” I think what I like best is what I see as transformations among genres, unified by horror: first a shipwreck scenario following Robinson Crusoe (which you tag), which segues into sci-fi, which segues into weird tale. Did you know you would be taking such turns when you first drafted, or were you pantsing it? What do you think the different genre elements contribute to the atmosphere, character development, and impact of the story? Why tree-fucking?

RH: A year or two before I wrote “The Seacretor,” I was watching a movie set on an island, and I started thinking about what I would write with that kind of setting. I came up with the final reveal rather quickly. I also had an older idea about someone crash-landing on a strange planet and becoming “fixated” by a tree, and it made sense to transplant that idea into what became “The Seacretor.” A tree just made sense as something that would be in that landscape, and I came up with what I thought was the most unexpected effect it could have on the characters. I remembered the idea when I owed Jack Bantry a story for Splatterpunk Forever. I didn’t have the group dynamic figured out beforehand, but as soon as I started writing it in first person, it all came together. I had a couple of Stephen King stories in mind—“Beachworld” from Night Shift and “Survival Type” from Skeleton Crew. I think there’s something really potent about a scenario where characters are stranded, because you’re immediately thinking about what you would do in that situation. How long could you do the sensible things before desperation drove you to something you wouldn’t have ever considered a few days before? And what if your only options ended up transforming you? There’s a contrast I like in the story about the beauty of the scenery with the loneliness of Ben, the protagonist, who may be losing Tanya to an annoying rival. In stories without a technological backdrop, I like the conflict to be born of something primal or ancient, and who knows how many strange aeons that island has been there?

9. Transcendent Transgression. Barring child pornography, can you imagine a story that would go too far to write? If so, what would it involve? If not, why not?

RH: I have found myself thinking certain scenes might be going too far sometimes. There is one in The Night Stockers where I knew some people were likely to quit reading then and there. There’s one in The Profile, too, where I thought maybe it was too much. But I also felt good about both those scenes, that they turned out well and had the effects I wanted. I even read the latter at KillerCon last year, and people laughed in all the right places. The wanton violations and mutilations of Von and Greg were perhaps viewed differently in 2012 when Genital Grinder was published than they would be now, but I think that’s probably also the appeal for readers just discovering GG… some stories may seem even more hardcore now than what I wrote them in 1999-2002 or so. I feel like a book with Von and Greg in such a different social climate is a bigger challenge now. I have to do it, though, one of these days. What would such a story look like? Our luckless duo will be attending college in this scenario. Anyone familiar with them can see why that would be such a disaster, with all the collateral damage of gender relations and generational and class differences, among others. Something with all the wrongness and hilarity of Edward Lee’s Header 2 that remains true to the respective personalities of our beloved degenerates, such as they are.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

RH: I have a Linktree here: https://linktr.ee/necroaf?utm_source=linktree_admin_share..

That covers a lot of ground, but I’ll also go ahead and throw in my Amazon page here: https://www.amazon.com/stores/Ryan-Harding/author/B01N1HSDZ5

And Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ryanhardmorbid

Thank you for this interview and the insightful questions!

About the Author

Ryan Harding is the four-time Splatterpunk Award-winning author of books such as Transcendental Mutilation, Genital Grinder and collaborations with Jason Taverner (the Agent Orange slasher novels Reincarange and Reincursion), Kristopher Triana (The Night Stockers), Lucas Mangum (Pandemonium), and Edward Lee (Header 3). He contributed the novella The Profile to the anthology Call Me Hoop, and his short stories have appeared in anthologies such as Brewtality, The Distended Table, The Big Book of Blasphemy, The New Flesh: A Literary Tribute to David Cronenberg, Splatterpunk Forever, Past Indiscretions, Into Painfreak, and The Year’s Best Hardcore Horror Vol. 3. His work has also been published in German, Italian, and Polish. Upcoming projects include a novel with Bryan Smith and the third book in the Agent Orange series.