Patrick C. Harrison III’s plan for his latest Pocket Nasty Queen Boss Slay not to be taken too seriously doesn’t keep it from being provocative. In this interview, he discusses how he put together his unusual main character’s perspective and, with it, a peculiar and entertaining read.

Queen Boss Slay

Sara is a working gal.

She deals in pain and pleasure.

The tools of her trade are… varied.

Men are her clients.

And Sara doesn’t like men.

She has her reasons.

She has a process.

And she’s ready to show you how it’s done.

The Interview

1. The Female Gaze. Especially when referring to horror film, people often talk about “the male gaze,” the point of view that determines what and how people see in a way that fundamentally empowers men and objectifies women. Horror’s male gaze typically belongs to a sadistic voyeur, someone who enjoys watching women get brutalized. One of Queen Boss Slay’s central projects seems to be to create the written equivalent of a female gaze, as Sara’s point of view dominates, and she objectifies and brutalizes men. Do you agree? Why or why not? What are the main components of Sara’s point of view, and how did you feel writing it? How might readers feel seeing men from Sara’s perspective? How might readers feel seeing through Sara’s eyes in general?

PC3: I guess I’ve never really heard of the male gaze trope. Certainly, no consideration of creating a female gaze went into my thinking, though it’s obviously written from the perspective of a female character doing terrible things. I think readers will see Sara’s perspective as demented and dripping with rage, though also somewhat logical at points, with nuggets of hard truths. I hope readers mostly see her thoughts of the world as absurd, if not comical. The book—and Sara by extension—was not meant to be taken seriously in any way.

2. Looking through the Female Gaze. Putting a woman’s perspective in the center and experimenting with giving her the power of the gaze typically reserved for men in horror is arguable praiseworthy, but as a man (I’m drawing conclusions from your pronouns), do you have the right to do it? How do you have the authority to represent female authority? What gives you insight into empowered femininity? For example, in a passage about women as sexual creatures, you write that women are “just as libidinous as men, if not more so.” While I know women who’d agree—and this belief was widely held until a couple of centuries ago—it’s still a controversial statement. Do you feel comfortable saying it on behalf of women in general? Why or why not?

PC3: Let me state the obvious first: Queen Boss Slay is a work of fiction. I didn’t write an essay on how women think or should think, and I don’t claim authority over anything aside from, hopefully, being able to make readers occasionally laugh, cringe, and retch. That being said, you ask if I have the right to write from a woman’s perspective, but it’s actually more than that. As an author, I have an obligation to write from perspectives I might not fully understand, whether writing about different genders or races or sexual orientations or whatever. It’s my job to crawl around in those areas and make sense of them and mold interesting characters out of what I discover on my quest. Whether the traits I’ve given the characters fit nicely into a reader’s perception of what that individual should represent in the real world is irrelevant. Does the character fit nicely into the story? Is the character interesting? Do they make you laugh or gasp or smile? An author shouldn’t be compelled to write only characters like themselves, but characters who are complex and interesting, and characters who may be wholly different than their creator. I agree with what Joe Lansdale said regarding a question of why he writes black and gay characters: “Because I don’t believe in segregated fiction where one group only writes about their group and no one can make an appearance that isn’t of your group.” (Check his Facebook post from February 11, 2023 for more on this and other questions—great read!)

3. Misandry. As the description above says, Sara doesn’t like men. She generally seems to view us as idiotic “ballbags.” While I don’t know that I’d be up for another smorgasbord of misogyny like American Psycho (though I think that book is brilliant), I must admit I found the focused misandry in Queen Boss Slay rather refreshing. To what extent did you set out to write an antidote to the piles and piles of representations of misogynistic killers in horror fiction? How serious is Sara’s denigration of all men? Do your representations of men critique masculinity? Why or why not?

PC3: This question requires the origin story of why QBS was written. Sara appears at the end of my book 100% Match. In the last chapter of that book, we see what she is, how diabolical she is. We don’t know why, and we don’t know anything of her back story because that story was not the narrator’s to tell. When 100% Match was written, I thought the story was over for Bart (the narrator) and Sara. But the story quickly became my bestselling book, and one review after another was asking for a sequel. So, I thought on that. Sara needed her own story, I decided, one completely separate from the book that birthed her. So, to answer the first question, in no way at all did I set out to write some kind of female response to misogynistic killers; I just had to continue the story, and this was the logical way to do it in my mind. When you ask how serious Sara’s denigration of men is, I’m not attempting to make some overarching criticism of men or masculinity. Her disgust for men in general, whatever her reason, is merely the tool carrying the story forward. Though I give many reasons, false or otherwise, why she does what she does, there’s no critique of my own that should be taken seriously. It’s a means to an end, I suppose.

4. Vengeful Spirit. How much should the sense that Sara is turning the tables on men, putting them in the victim positions usually reserved for women in horror, make the horror more fun? Does Sara’s edge of vengeance make her actions more morally acceptable? Why or why not? Since Sara often refers to early-life trauma, particularly rape, related to her present-day activities, your story seems connected to the rape-revenge tradition in horror film and fiction. How would you relate Queen Boss Slay to a film such as I Spit on Your Grave (1978) or a book such as Monica O’Rourke’s Suffer the Flesh?

PC3: I love a good revenge story. Kill Bill, Death Wish, Payback—man, those are fun! I Spit on Your Grave is exactly the type of connection I want readers to make with QBS, up until that kinda gets turned on its head. I want readers to be appalled by the things Sara does, but also have a sense of understanding, like men as a whole deserve her wrath after what she’s been through. She’s an antihero, by god, fighting for all women because of her history of trauma! Or is she the villain? I’ll let the reader decide for themselves. As far as Suffer the Flesh, nothing else I’ve ever read or written relates in a substantive way to that masterpiece of depravity.

5. Misogyny? While Sara openly advertises her hatred of men, she shows more than a little disapproval of women. Why are the hypocritical church ladies important to Sara and important to the story? In addition to showing examples of women who seem like they might be as loathsome as men, you devote some pages to the quickly-becoming-classic “the man or the bear?” debate that asks whether, if encountering one while alone in the wild, a woman should choose to confront a man or a bear (incidentally, I also discussed this topic with Kenzie Jennings in a recent interview). The feminist-leaning answer is the bear. Sara finds this answer absurd—does she also find the women who answer that way absurd? Why or why not? Do you agree with her? Why or why not?

PC3: I think while Sara sees men as the preeminent problem in society, she sees herself as the only real antidote capable of combating the system. She views other women as weak enablers, allowing men to ascend to their status at the helm by sheer submissiveness and lack of action. Interestingly, in that scene where the bear question is posed, Sara is talking with a woman who shares the same basic beliefs as herself regarding men. Sara simply believes she knows what to do about it, while the other girl is ignorant and weak. As an aside, judging by my reviews as a whole, probably 75% of my readership are women. When I completed QBS—with all the crazy, repulsive, depraved things within the story—it was this scene that most worried me regarding pushback from those readers. I thought there was a real possibility folks might call for my head over a few paragraphs of fiction. But I kept it in there because it was exactly how Sara’s character would respond to the bear question. And, besides a few reviews, no one seems to have cared much.

6. Showing Us How. When you write about Sara addressing her online audience, she addresses that audience, but you also break the fourth wall and have her address readers. Why? As the description above indicates, Sara at least behaves as if what she does has an instructional dimension. Why does she feel driven to teach, and what exactly does she hope her students will learn? At one point she concedes that much of her audience is male… is she addressing the men, too? Why or why not? If what she does is instructional within the story, is your story instructional? If so, what are you teaching and why?

PC3:100% Match is much the same way in how the reader is along for the ride, experiencing everything in present tense as the character goes through their routine. From the beginning, I wanted to make QBS a How to of sorts, in part to distinguish it from 100% Match. I actually ended up removing a lot of the instructional content because I thought it was getting in the way of the story. I’m not sure why Sara is compelled to teach. In my mind, I kinda saw it as someone (the reader, presumably) asked her about her lifestyle, so she’s bringing this person along to show them the ropes. I don’t know that she believes “much” of her audience is men, but she certainly knows some are. I think she addresses the men in the audience—you included, Andrew—with a roll of the eyes and a middle finger. I thought of having her mention at some point how disgusted she was about a man (me) writing her story, but it just didn’t work out on the page the way I saw it in my head.

7. Livestreaming. Perhaps because I’ve written extreme tales involving cameras, too, I’ve asked a couple of authors, and now I’m asking you—why do you think videos and streaming images are so prominent in extreme horror? Sara streams the highlights of her depraved activities online for eager viewers. What does her practice say about exhibitionism, and what does her audience’s eagerness say about voyeurism? Are horror authors similarly exhibitionistic with our depraved imaginings, and are horror consumers similarly voyeuristic with their eagerness for extremes? Why or why not?

PC3: These are really interesting questions. There certainly is no shortage of livestreaming/video torture stories. In fact, Home Video by Matt Shaw was one of the first extreme horror books I read. I think this subgenre of a subgenre is so prevalent, in part, because we now live in a world where what was once taboo is now easily accessible with a few clicks. When I was a kid, porn wasn’t something you could see on a daily basis. The first porn I saw was a crumpled Hustler magazine I found in a lunchbox in the middle of a field. Now it’s everywhere. You can look at porn on X, for Christ’s sake. And then there’s OnlyFans, which was kinda the inspiration for what Sara does. What’s interesting, and horrifying, is that there undoubtedly really are people who watch or want to watch the types of things Sara does. Why? I’ll leave it to the psychologists and sociologists to figure out, but there is a certain segment of the population that desires to see what shouldn’t be seen. Has your Instagram algorithm ever gotten to where it’s only showing you people getting hit by cars or mauled by animals? Like, I don’t want to see that shit! But… I also kinda do. Extreme horror and splatterpunk play much the same way. So many readers of such works say they’ve had to put the book down for a while, that a certain scene made them nauseated or upset. But why did they pick the book back up if it made them feel that way? Pure curiosity? To see how far the writer would go? To prove to themselves they can get through it? On that topic, I end my novella Grandpappy with a subtle shoutout to the reader, through the narrator’s voice, expressing self-admiration for making it “through Grandpappy.” It is an accomplishment, I suppose.

8. BDSM. Your cover suggests BDSM, and at one point Sara calls herself “The baddest BDSM bitch in the land!” Why is BDSM part of Sara’s self-image? How do her activities relate to BDSM outside of fiction? How thin is the line between getting off on domination and pain and getting off on injury and death?

PC3: This aspect of Sara was introduced at the end of 100% Match. As I said previously, initially, there was no sequel planned. But when I decided to go for it, I had to roll with what Sara was, a demented dominatrix. I think Sara is indifferent to BDSM and kink, but it offers her an easy way to dominate men. Many of them willfully come to her to be dominated. She is more than happy to oblige. Though there are certainly people who are attracted to the D/s lifestyle and power dynamic, I don’t think any of Sara’s activities relate at all to real-world BDSM. As someone who has spent time in the kink community, I can say that trust is everything and equal power between the ‘D’ and the ‘s’ is very important. And the line between getting off on domination and pain versus injury/death is so expansive it cannot be measured. There is no relation.

9. Pocket Nasties. Queen Boss Slay is second in your series of Pocket Nasties, following the successful 100% Match, which I haven’t yet had a chance to read, but you told me it is loosely related. I had no trouble following Queen Boss Slay as a standalone, but I’m curious—without spoilers, can you tell me and readers starting out like me about the connections? Also, what are your plans for upcoming volumes in the series? What characters, themes, or ideas are likely to reappear? Is there anything nasty you wouldn’t do?

PC3: As I said previously, 100% Match is told in a similar style—first person, present tense, spoken to the reader in a comedic fashion. But it’s wholly different. Far less graphic. It doesn’t even contain profanity, and I see it more as a black comedy than a horror story. The plot follows a man named Bart, a thirty-something burger flipper in search of his perfect match. He’s obsessed with compiling statistics that will help him attain his goal of finding his true love. He’s also very awkward, in the worst of ways. And he just might be a serial killer. Sara from QBS comes into Bart’s life as one of his love interests, and things don’t exactly go as planned. For the upcoming Pocket Nasties, there will not be a connection from one story to the next, at least not with the next few. They’re going to be extreme horror/splatterpunk stories meant to do what those genres are meant to do—shock and appall, and occasionally make one think. The next one is called Firecracker Kings, a previously published story that I have expanded. Following closely after that, a tale named Panty Mail. If I don’t get canceled for that one, I have a couple more loaded and ready to write.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

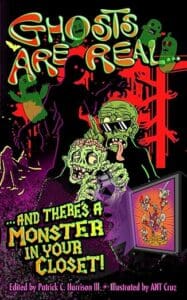

PC3: I’m most active on Facebook. I also have a substack titled PC3 Horror, where I do movie reviews and keep subscribers updated on new releases. All of my books can be found on Amazon, and I also sell my books on Etsy, along with vintage books of all types. I’d also like to let any of your readers who are not extreme horror fans know that I write non-extreme stuff as well. In fact, my latest release is an anthology of middle grade/quiet horror I curated, titled Ghosts Are Real and There’s a Monster In Your Closet.

About the Author

Patrick C. Harrison III (PC3, if you prefer) is an author of horror, splatterpunk, and all forms of speculative fiction. He has written over a dozen books, including 100% Match, Grandpappy, Vampire Nuns Behind Bars, and Queen Boss Slay, and his short stories can be found in numerous anthologies. PC3 lives in Wolfe City, Texas with his family and their loving doggo—Nora.

Great interview with a great author! Love what PC3 said about readers thinking Sara’s perspective is “demented and dripping with rage, though also somewhat logical at points, with nuggets of hard truths.” That’s exactly how I felt, and it was hilarious and uncomfortable to occasionally find myself in agreement with this absolute psychopath. Like how I felt reading the “Cool Girl” speech in Gone Girl.