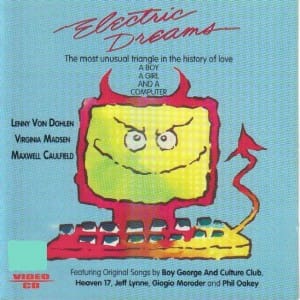

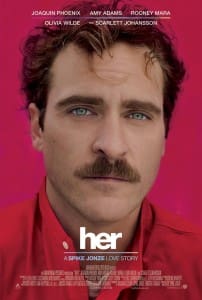

Spike Jonze’s Her has won and may continue to win some of the year’s biggest awards, which was the final push I needed to see a movie of a sort I usually reserve for smaller screens. I was also curious because it resembles one of my favorite movies circa age 8, Electric Dreams (1984, math slightly misleading).

Electric Dreams stars the talented and forever-beautiful Virginia Madsen as well as “Hey he was on Twin Peaks!” Lenny von Dohlen. The latter buys a primitive home computer, which becomes sentient after he spills champagne on it, and he and the computer both fall in love with musician neighbor Madsen. Competition and a blend of comedy and pathos tinged with (adult me realizes) odd homoeroticism result in a film that, much like Her, can be enjoyed as a sweet fable about love and technology or a much deeper meditation on artificial intelligence and how it helps to map (as well as confuse) the boundaries of the human. At age 8, I mostly thought it was cool because I identified with the nerdy lead and liked the idea of a computer I could hang out with (imagine what you will about latent whatevers).

Her casts the computer as both the love object and the opposite sex from the male lead, Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix), so the homoeroticism of the earlier film disappears, but Jonze gives us something potentially much more interesting in its place: the computer, Samantha (voice of Scarlett Johansson), is very conscious about the implications of her lack of a human body, and “her” consciousness creates a consciousness throughout the film about the potentially arbitrary relationship between gender and embodiment. Very early in the film, as Theodore sets up his new (as-advertised) sentient operating system, he gets to choose between male and female. The binary is as hard-wired as the position within the binary is fluid. This conception of fluidity, though not all-encompassing, leads the film to explore and challenge other aspects of human sexuality as seemingly “natural” as gender, sex, and opposite-sex desire, considering possibilities of polyamory as well as conceptions of interpersonal experience that break down individual subjectivity.

To carry this analysis further would go too far into the realm of spoilers, but briefly, the film ultimately aligns traditional human sexual identities with analog media and linear storytelling while it aligns post-human possibilities for identity (like Samantha) with digital media and its affinities for infinitude of detail (the ever-better resolution of Hi-Def) and the non-linear (the benefits of random-access as opposed to analog memory formats and linear linguistic syntax). This move isn’t intellectually revolutionary, although these ideas aren’t very mainstream either, so I don’t hesitate to say that Her is at least as subversive as its 80s predecessor, and it is really a lot better in other ways too (getting to that).

Thank you for continuing to read after the two previous dense paragraphs!!!

Bottom line: Her doesn’t have much new ground to cover in terms of the basic issues it breaches with artificial intelligence, but it does enter some compelling territory with its thinking about gender and identity, which, if you think about it, any movie bold enough to call itself by the female pronoun (objective case, no less) really ought to do.

Other than its well-realized premise and great lead performers, the film’s most striking features are broadly its cinematography and score, specifically its color palette, depiction of Los Angeles, and selections from Arcade Fire’s most recent album Reflektor (the really good part of the album, i.e., the second half, side, record, whatever). The film’s Los Angeles is of an unspecified future in which the city’s public transportation system is somehow as regular a feature in upper middle-class existence as it is in New York; the skyline is beautiful, clean, and already full of buildings with green roofs; and every view is clean, sparkling, and friendly. This fantasy version of a place people sometimes unfairly call la-la land finds its complement in settings and costumes coordinated with post-production magic to create a stunning system of muted pastels and translucent primaries that lend almost every shot an aura of artificiality that is nonetheless gorgeous. In other words, Her‘s aesthetic matches Her, and the result is at times almost as mesmerizing as Theodore finds Samantha.

Arcade Fire’s oneiric tones underscore the film’s consciousness of its status as fantasy about fantasy, self-consciousness about self-consciousness. Thus Jonze continues on a postmodern trajectory begun in his early collaborations with Charlie Kaufman but in his own writing finds sensitivity and sympathy for his characters that were scarcer in those more sardonic works. I’m not sure that Her is his best movie ever or the best movie of the year, but it is definitely worth attention. The combination of sweet and smart is awfully endearing.

Comments are closed.