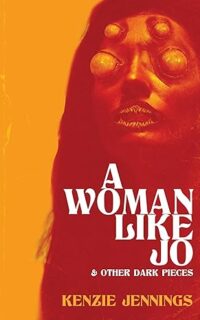

Accomplished dark fiction author Kenzie Jennings discusses her latest collection of short fiction, A Woman Like Jo & Other Dark Pieces, a work with eclectic styles and themes sure to inspire thrills and thought.

A Woman Like Jo & Other Dark Pieces

There are those who are familiar with a woman like Jo, who steals a man’s heart during his own midlife crisis on the other side of the world…

…or a woman like Deandra, who robs the wealthy during the stormiest night of the season when the dark reveals its secrets…

…or a woman like Cassie, who collects airline travel perks no matter the cost to her, or others’, well-being…

…or a woman like Heather, who succumbs to a lifestyle brand, the kind one doesn’t ever recover from…

…or a woman like Jillian, who promises herself, after her divorce, to never be seduced by a stranger…

…or one out of a number of other women whose stories are told here, as cautionary tales, perhaps, of the absurd, the grotesque, the demented, the forlorn, the brazen, or the downright strange.

Perhaps even you may find some of them awfully close to home.

The Interview

1. A Woman Like…. Your book’s introduction mentions that you “like writing about interesting, smart women,” and the book’s closing, nonfiction piece refers to you once taking a “Feminist” stance out of “empty obligation,” but you don’t quite claim the feminist label for the book. So, to clarify: do you think of the book as feminist? If so, how would you describe the book’s feminism? If not, how would you describe the book’s focus on women?

KJ: I’m somewhat…SOMEWHAT… conflicted about describing this collection, and pretty much anything I write, as “feminist.” The ideology seems so often misunderstood and disrespected. On the one hand, yeah, it makes sense to think of it that way as it’s a work of horror centered predominantly around women characters and their experiences in a genre that typically doesn’t give them any sort of equal footing to their male counterparts. On the other, I can see where it might not be as there are some troubling moments involving victimization tropes that seem antithetical to what’s popularly considered “feminist.”

Then again, feminism exists to remind us that women are human beings, and human beings suffer.

So… perhaps it IS feminist.

As for the story “Always the Bear,” the bear debate fascinates me. The point of it is centered on the unpredictable behaviors of men, but we’re forgetting something here: Feminism centers on the treatment of women as equals to men… basically, to be treated as human beings, rather than “less than.” So, wouldn’t women likely be a threat to men as well? I just wanted to toy with that idea because every time I’d heard the debate brought up, I couldn’t help but consider that humans, overall, are utterly unpredictable.

2. Treacherous Triangulations. In the stories “A Woman Like Jo” and “Tell Greg,” the female protagonists have problems with treacherous men, but their ultimate confrontations are with women. I see triangulations—do you see them, too, and if so, were they intentional? Roll with me: in these triangulated relationships, the second woman could be helping to mediate the emotional and physical ties between the protagonist and the treacherous man, or the treacherous man could be mediating between the two women. What sort(s) of mediation might happen and why? Intentional or not, triangulated relationships are among the advanced tools in your character-building toolbox: what other tools should readers watch for?

KJ: That’s an interesting term – “triangulation.” I don’t think it’s intentional… well, at least not until I understand how the climax or ending, and some of the characters’ motivations, are going to be revealed. (I realize that’s not an answer to your question centering on what sorts of mediations might happen, but it’s all I have for now.) One of my character-building tools is the element of surprise in that sometimes, we’re not going to know much about a character’s motivations until just the right moment. Quite often though, I don’t even know when or what that is. They’re leading me to what’s happening. As for other tools I tend to use, readers ought to be aware that protagonist likeability, and with that empathy, isn’t always going be a factor. It’s great to have a heroine to root for, sure, but do we have to be friends with her… or do even want to be friends with her? Is that absolutely a story-killer to have a protagonist who’s unlikeable?

3. Problems and Solutions I. The story “Perks” focuses a great deal on body image and the shaming of people, especially women, who don’t fit within societal norms, which the story embodies within an abusive male character on an airplane with the self-conscious female protagonist, Cassie. This man emphasizes to me, at least, that patriarchal scopophilia is responsible for much public shaming; by “patriarchal scopophilia,” I mean basically that we live in a world ruled by men that is designed for men’s visual pleasure. How much do you think the pain Cassie experiences from her body consciousness comes from the world of men? The airplane’s “perks” program gives Cassie a way to fight back. The perks are a great fantasy, but can you think of anything like the perks in real life that would allow resistance to the violence of societal norms? Is violence in response to those norms necessary for change? Why or why not?

KJ: The pain Cassie endures definitely comes from that sort of “patriarchal scopophilia” you describe, and the ending only serves to enhance that with a dollop of internalized misogyny (I can’t spoil anything here). In reality, I don’t think violence sends any sort of “correct” message in order to enact change. Violence tends to breed further violence. However, it’s an interesting image, one that horror plays around with quite a bit, and if it’s a consistent patriarchal-bred vantage, that women exist for men’s visual pleasure, why not confront that with what that sort of… man… comprehends, which is, ultimately, violent retribution… but in the form of body horror (since it’s about body image to begin with)?

4. Queer the One You’re With. The main characters in the story “The One You’re With” are a same-sex couple, Gia and Marielle, and the story involves marital distrust that, right or wrong, blossoms into raging paranoia. Why make the central couple two women? Is the couple’s queerness relevant to the plot? Why or why not? More queer characters seem to be showing up in horror lately. Why do you think that is? Do queer perspectives up the horror ante in this story? In general? Why or why not?

KJ: Their queerness isn’t relevant to the plot. The story could be about any couple, really. I like writing about relationships, particularly the horror that can emerge from them. In this story, I wanted to have an ordinary couple tormented by an intrusive thought written on a wall, and Gia and Marielle were quite ordinary. I know that’s not a particularly thought-provoking answer, but it’s what I have.

As for queer characters and perspectives in horror, we’re seeing a horror Renaissance, and it’s fantastic and long overdue. Queer perspectives do up the horror ante, as much of the horror they face centers around bigotry and the physical and psychological violence that stems from it. There is so much reactionary material there, so much horror to write in response.

5. A Story Like…. Part of your collection’s fun comes from your play with form, notably the email epistolary style of most of “The Academic Hearing Committee’s Final Decision” but also switching tenses of narration and mixing in bits of other media in other stories. “The Third Woman” is formally adventurous in a way I won’t give away (feel free to comment). How do you know what form(s) a story will take? Which story in this collection do you think is most formally successful? Which was the most fun to write, and why? Do you see yourself as experimenting in your stories, or does the variety come from another motive?

KJ: I usually know what form the story will take, but it’s never set in stone. In other words, it depends on what I later decide what to do with it. “The Academic Hearing Committee’s Final Decision” was a long-planned story, though, one that was inspired by the barrage of faculty-and-administration email chains I’m confronted with every week. I’ve loved the epistolary form ever since I first read Dracula. My debut novel, Reception, was close to becoming a tale told partially in texts, but I needed the pace to go off the rails at the halfway mark, and I felt that texts would detract from that pacing. I’d love to write a novella that way, though, someday. To be honest, unless you’re well-organized, it’s difficult to do well since you have to pay close attention to the finite details in the format (dates and names in email exchanges, for example), and I’m quite scattered.

I don’t know which of the stories in A Woman Like Jo is the most formally successful, but “The Third Woman,” probably the most serious work of fiction in the bunch, was the most engaging to write because of its form, which lacked the finite bits of “The Academic Hearing Committee’s…,” thankfully. I also knew exactly where it would take me and how it would get there, and that was a new experience for me, too.

6. Academic Horror. As an English professor, you’re writing what you know when you make an academic committee the focus of a horror story, but you’re also participating in a long tradition, some call it a subgenre, referred to as Academic Gothic or simply academic horror (consider recent work by Cassandra O’Sullivan Sachar and David E. Grinnell). Are you familiar with this tradition, and, if so, how do you see yourself contributing to it? Whether or not you had the tradition in mind, what’s horrifying about academic life? One example comes up in both “The Academic Hearing Committee’s Final Decision” and your nonfiction “It’s Never Been About Beauty”—the status of contingent faculty. What are you saying about the plight of adjuncts? Higher education in general?

KJ: I’m vaguely familiar with the subgenre (I didn’t know it was called Academic Gothic. That certainly suits!). However, I don’t see it as often in horror as I’d like. It really ought to be more popular as there are plenty of horror authors in academia, and the internal and external politics involved in and around our work are pretty horrifying. As for the treatment of adjuncts, that is just the tip of a problematic system that is unbalanced and unfair by design. I spent far too many years as an adjunct, trying to get hired full-time at my local college all the while working several other part-time jobs to make rent and pay my bills (of course, medical care was out of the question since I’d no benefits.). Writing a horror story about a contingent faculty… revolt… seemed fitting.

Also worth noting, I live in Florida where all facets of public education are being actively dismantled before our very eyes. Granted, Florida is a sampling of what seems to be happening all over the country. This is already a horror story underway, bit by book-banning bit.

7. Repetition Compulsions. Readers familiar with urban legends will recognize the basic scenario in “Habits” within a few sentences, so like most urban legends and campfire tales, the art, as well as the fear, is in the retelling, the repetition. The twist you put on the end makes it particularly about repetition. As the title indicates, “Same Booth, Once a Year” also involves repetition, particularly a repeating, escalating horror. When and why is repetition scary? When retelling a tale as in “Habits,” how do you make the repetition scary? In “Same Booth, Once a Year,” which is scarier, the booth visitor’s repetitive routine, or what he is? Why?

KJ: To me, it’s the deeply unsettling feeling of repetition that’s scarier. Routines and habits, layered repetitions, feel eerily unnatural. I don’t know why that is, and I don’t know the art of it (how to craft it well), but I think, in horror, it kind of feels like the Other is getting ready to perform. It’s that sort of sensation. It’s like Patrick Bateman getting ready to go about his day, or the pod people practicing facial expressions in a mirror, or a Stepford wife having to reboot after going haywire… When I read that sort of thing, I get the creeps.

8. World Building. “About Her Given Name” is the only story in the book for which I wish I’d read your Author’s Notes first: I enjoyed the story on first read, but knowing it’s an origin story for a larger world you’ve written other stories in makes it seem cooler in retrospect. Other than to answer questions that came up in related works, why focus on “her given name?” Why is naming so meaningful for these characters and their world? How deep are the ramifications of this story’s central conflict—how much does it shape the world you’re building? Your notes mention a work in progress set in this world. Do you see yourself using this world in many works to come? Why or why not?

KJ: “About Her Given Name” is a love letter to readers who enjoyed Red Station (my contribution to Death’s Head Press Splatter Western series of novels and novellas) and its heroine, Clyde Northway. The title is important in particular since the story focuses on her name’s origin and the beating heart of her strange world. The name “Clyde” has often been brought up by readers and critics, which I somewhat understand since Clyde is more notably a conventionally male name. However, in that era, it wasn’t a particularly uncommon name for women. Names in her world, one of secret societies and trained killers, though, are important since the orphaned girls brought in and trained in that world enter without an identity, so once they’ve established some sort of name for themselves, that becomes a step closer to their own sense of individualism. Red Station, however, reveals none of this, as its story, a slasher, centers around a family of serial killers who trap travelers in their station home in order to kill and rob them. Clyde is, essentially, the badass final girl.

Northway is my current work-in-progress, a novel that focuses on who Clyde is and what happens to her after the events of Red Station, going back and forth in time. “About Her Given Name” is a taste of what’s to come. The story introduces her nemesis and her mentor, as well as the primary characters’ motivations, so they certainly help shape Northway and establish the conflict happening. I liked having the short story as a launchpad for the world-building of the larger work.

9. Problems and Solutions II. The creative nonfiction piece that closes the volume, “It’s Never Been About Beauty,” brings back the issue of patriarchal scopophilia (I’d say) by charting how you’ve been affected by an appearance-obsessed culture of abuse among girls and boys, women and men, from age five through adulthood. Would you call it a horror story? Does it imply a call for change? The story alludes to how this belittling culture affected how you saw yourself as a writer. How much does it affect your writing now? This piece is very effective. Should readers expect more creative nonfiction from you?

KJ: Thank you! “It’s Never Been About Beauty” is definitely a horror story, one with a very adult lesson learned. It may imply a call for change, but I don’t think it’ll have much readership to enact it. I published it in this collection so that people could see me through an individual, authentic experience, but I know that it must resonate because this sort of abuse is so far-reaching. So many of us have been through it and continue to go through it. It doesn’t help that the current political landscape here in the U.S. has brought out a constant stream of misogynistic personal insults on physical attributes rather than valuable intellectual discourse. That being said, there’s more activism as a result of that happening. This generation of women in particular isn’t tolerating it whatsoever, and I admire them all for it.

As for expecting more creative nonfiction from me, absolutely. I love writing it. It grounds me.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

KJ: Readers can find me at kenziejennings.com (my website that is still in serious need of a storefront) and can find my work on my Amazon author page (Kenzie Jennings), through Dead Sky Publishing (and their bookstore links), and through Godless.com.

I am also all over the chaotic social media landscape:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kenzie.jennings

Instagram: @kenziejennings2

About the Author

Kenzie Jennings is an English professor and the author of the collection A Woman Like Jo & Other Dark Pieces as well as the Splatterpunk Award-nominated books Reception, Red Station, and Always Listen To Her Hurt. Her short stories have appeared in a number of anthologies including Queens of Death (Bludgeoned Girls Press), Worst Laid Plans: An Anthology of Vacation Horror (Grindhouse Press), Baker’s Dozen (Uncomfortably Dark), and Hot Iron and Cold Blood: An Anthology of the Weird West (Death’s Head Press).