This morning I wrote in an email that I have no interest in memoir.

Poe called it the imp of the perverse; Foucault’s inversion was the perverse implantation. Perhaps my correspondent saw the imp coming before I did. Perhaps he sent it.

At age eighteen, I entered a fictional world.

No, not fiction-writing. I recall starting a novel in the second grade. It was a choose-your-own adventure about two boys who got kidnapped, taken away on a plane, which then crashed on an island. Quite exciting. Never finished. Part of my brain has always been in la-la land.

Mundane: going off to college. That’s the transition I’m talking about.

Surreal: driving from Georgia to Massachusetts with both my parents, who reminisced almost incessantly despite having been divorced for most of the life I remembered.

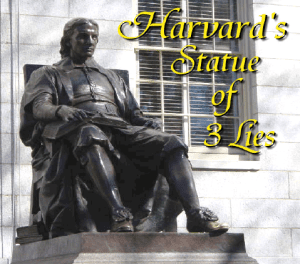

Unreal: destination, Harvard.Granted, as American tales go, a lower-middle-class Southern kid getting into Harvard is hardly a movie of the week. I do not include my story as such among the unrealities, the fictional phenomena, I am pondering.

I assume the gentlemen in the second photo willingly published it, one of the top hits on the Google search “John Harvard statue,” and are of legal age, and thus I use it as an example here. Click photos for sources.

I assume the gentlemen in the second photo willingly published it, one of the top hits on the Google search “John Harvard statue,” and are of legal age, and thus I use it as an example here. Click photos for sources.

The prime unreality I wish to consider is/are the places where I was educated. While I got around to places that together ain’t too shabby in any company, nevertheless, in some company, questions about where one was educated generally produce answers like mine—the Ivies—or their kin, Stanford, Berkeley, one of the former Seven Sisters, or for color one of the liberal arts elites like a Swarthmore or an Oberlin, etc. In other company, like my own family and the circles in which I grew up, the subject of such places tends to produce (1) starry eyes and/or (2) suspicious eyes.

The defining difference between these kinds of company is certainly not average IQ; it’s average income.

The starry eyes? At age eighteen, I went to a place that on my home-world exists only in movies and TV shows.

The suspicious eyes? At age eighteen, I crossed class boundaries, relocating behind enemy lines. I am become snob, transgressor of values. I defected.

And nowadays, as the wealthy in this country continue to manipulate media and legislation as well as the economy to continue widening the income gap and have the gall to accuse anyone pointing out their tactics of “class warfare,” class defection is serious business. I saw The Purge: Anarchy. And as Michael K. Williams says best, “Time to bleed, rich bitches.” Seriously.

But first, let’s fixate on the stars. My personal experience of college is in fact such a cliché in fiction that I hesitated to set parts of Descending Lines at Harvard, but I couldn’t help it—that’s where it unfolded in my imagination because that’s where I knew such eccentric people might do such things in such ways (if the supernatural were possible). I lived in that setting. And yet whether it’s faked in schlock like With Honors or real as in Love Story or pretty convincing as in The Social Network, etc., now my primary contact with a world I’m happy to revisit but wouldn’t choose to inhabit is, once again, fiction.

I quote Candyman: “It is a blessed condition, believe me. To be whispered about at street corners. To live in other people’s dreams, but not to have to be.”

Harvard is an American legend. Its power is, like Candyman’s, supernatural not in the ways it actually exists but in the ways it does not have to exist.

Harvard is an American legend. Its power is, like Candyman’s, supernatural not in the ways it actually exists but in the ways it does not have to exist.

Not having to exist, however, is not the same as not bearing responsibility for being. Both The Purge and Candyman show that one can suspend the laws of both government and physics and still be trapped by harsher laws of transcendent justice. The bleeding times.

The suspicious eyes.

My own eyes become suspicious, bringing me to a secondary unreality. Did I really go to Harvard at all?

Yes, I attended classes there. I have a diploma. I have memories of living in Harvard Yard, then down by the Charles River for three years in Winthrop House. But I was a “floater.” I never had a “blocking group.” I had plenty of extra-curriculars, but I never “comped” anything that you’ve heard of, like The Advocate or The Crimson or The Hasty Pudding or the Lampoon because as far as I could see, all of those organizations valued socioeconomic class over intellectual merit. I knew, and knew about, people in all those organizations. And I paid attention to their family backgrounds, mostly very different from mine.

In college, I was naïve enough—because they got me in—to think intellectual voracity and achievement mattered most. Only later did I realize that, professionally speaking, C students from the Ivy League are far more likely to become Presidents.

In college, I was naïve enough—because they got me in—to think intellectual voracity and achievement mattered most. Only later did I realize that, professionally speaking, C students from the Ivy League are far more likely to become Presidents.

At age eighteen, I entered a fictional world.

Suspicious?

Comments are closed.