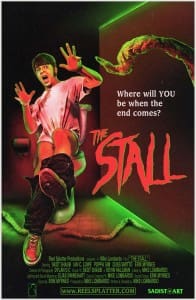

I’ll start big: Mike Lombardo and Reel Splatter Productions‘ new short film “The Stall” now ranks near John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) on my list of favorite Lovecraftian films. For an interview with Mr. Lombardo, please see my guests’ page; for a review of “The Stall” as well as Lombardo’s interrelated short stories “Play Place” and “I’m Dreaming of a White Doomsday,” keep reading here.

The word “Lovecraftian” is key here because like The Thing, which owes more direct credit to the earlier Hawks/Nyby film and the John W. Campbell short story “Who Goes There?,” “The Stall” clearly springs from the imagination of Lombardo rather than that of (R.I.P.) H.P. Lovecraft. Nevertheless, the rare cinematic adaptations that credit Lovecraft stories and are actually good–most of which are directed by Stuart Gordon–elaborate so much on Lovecraft’s raw material that they often lose the eldritch, unspeakable quality that makes Lovecraft’s prose like no other’s. Gordon tends to lose it by injecting a lot of kinky sex, but the trade of transcendent tone for hypnotic kink still makes for good moviegoing.

The word “Lovecraftian” is key here because like The Thing, which owes more direct credit to the earlier Hawks/Nyby film and the John W. Campbell short story “Who Goes There?,” “The Stall” clearly springs from the imagination of Lombardo rather than that of (R.I.P.) H.P. Lovecraft. Nevertheless, the rare cinematic adaptations that credit Lovecraft stories and are actually good–most of which are directed by Stuart Gordon–elaborate so much on Lovecraft’s raw material that they often lose the eldritch, unspeakable quality that makes Lovecraft’s prose like no other’s. Gordon tends to lose it by injecting a lot of kinky sex, but the trade of transcendent tone for hypnotic kink still makes for good moviegoing.

Carpenter, without drawing too directly on Lovecraft’s storylines, captures the transcendent tonal quality of the Lovecraftian in his early 80s masterpiece with mind-boggling, big-budget (for its time) make-up effects and lush frozen landscape cinematography. Lombardo, an indie filmmaker shooting in the pizza shop that provides his day job, accomplishes a comparable feat with big ingenuity instead of big dollars.

“The Stall” works mainly because it pivots around a compounded tonal shift: it’s marketed as horror, so you know where it’ll end up, but it starts as comedy, hints at becoming a crime thriller, and finds at its end a bleak, humorless world where most viewers would least expect it.

Many of Lovecraft’s stories tend to end in the same way because they begin in the same way: with a protagonist leading a normal existence that is about to be torn away forever by unspeakable horrors. Lombardo captures a humdrum, normal existence by drawing on his own experience in food service, and he provides the film’s greatest humor in his satirical portraits of typical pizza parlor customers, which range from the woman who requires the perfect portion of cheese to the stoners who believe cutting the same-sized pie into twelve slices will result in even more food.

While these typical-day frustrations unfold at the appropriately-named Pickman’s Pizza, two would-be burglars, who turn in some of the film’s best (albeit stereotypical) acting, plan to rob the place, setting up a twist from comedy to crime-thriller.

Just before the robbers arrive, though, our pizza-selling protagonist must excuse himself to visit the titular restroom stall, where he first hears gunfire and then hears chanting that unleashes “the end” promised by the short film’s promos.

Now for the real tonal shift: you might expect a guy taking a crap at the end of the world to be the setup for some slapstick poo-and-blood horror, but what Lombardo delivers instead is more likely to make people react to public restrooms like they did to taking showers after they saw the original Psycho (1960). Nimbly (at least from the viewer’s perspective) moving the camera around the tight space of a bathroom stall, the film captures the protagonist’s growing confusion and fear as he hears and eventually sees the horrors unfolding in the pizza parlor and making their way to the bathroom.

We see blood and tentacles–the blood effects, which involve different mixtures for a variety of icky consistencies, are particularly noteworthy–but the real horror stems not from Reel Splatter’s trademark gore but from two things. First, the film involves well-framed reaction shots that only imply the unshown horrors that the character is reacting to (a technique straight out of Lovecraft, who will describe characters’ reactions to horrors that the stories don’t represent because characters can’t fathom them).

We see blood and tentacles–the blood effects, which involve different mixtures for a variety of icky consistencies, are particularly noteworthy–but the real horror stems not from Reel Splatter’s trademark gore but from two things. First, the film involves well-framed reaction shots that only imply the unshown horrors that the character is reacting to (a technique straight out of Lovecraft, who will describe characters’ reactions to horrors that the stories don’t represent because characters can’t fathom them).

Second, the sound editing on this film may be its greatest accomplishment. Lush and layered, the sounds include chanting, static, musical strains that appear and vanish, and basically suggestions of another world impinging on our own–the soundscape is the apocalyptic inter-dimensional invasion that we do not see, and it works beautifully, right through the closing credits, where the synth-rock evokes, to me at least, none other than John Carpenter (or perhaps his collaboration with Ennio Morricone on The Thing) at his apocalyptic best.

Second, the sound editing on this film may be its greatest accomplishment. Lush and layered, the sounds include chanting, static, musical strains that appear and vanish, and basically suggestions of another world impinging on our own–the soundscape is the apocalyptic inter-dimensional invasion that we do not see, and it works beautifully, right through the closing credits, where the synth-rock evokes, to me at least, none other than John Carpenter (or perhaps his collaboration with Ennio Morricone on The Thing) at his apocalyptic best.

The apocalyptic triumph of “The Stall” is perhaps Lombardo’s most noteworthy recent work, but while the cinema is his calling, he turns out to be a talented writer, too. The 2012 short story “Play Place” (details on how to get the stories are on the guests’ page) follows lines initially similar to “The Stall,” focusing on a food services employee who observes caricature-ish customers at McDonald’s who together satirize our fast food nation’s ridiculous assumptions about the industry. For example, one woman asks the underpaid employee whether the food is right for her son, who is “Hypo-Glaxominicallyk,” and she is particularly interested in knowing whether the food contains “Ribonaxtein 7.” I’m a college professor, and I don’t know what either of those quoted terms means. To expect a McDonald’s employee to know–and then to be shocked when the same employee is at least clever enough to answer the stupid question “Is it even organic?,” with “yes, our food is carbon based,” sums up a lot about the classism and extreme self-involvement that make some people’s play places other people’s hells.

And that’s an idea, of course, that Lombardo make almost literal when a zombie apocalypse overtakes the restaurant, and the protagonist, having been punished for sassiness with the foul task of cleaning the children’s Play Place–an area consisting of slides, crawling tunnels, and a ball pit– finds himself removed enough to survive while he watches almost everyone else die. Like “The Stall,” all humor drains quickly from the tale once the slaughter begins. Not only does the move into seriousness signal an evolution in Lombardo’s creative tendencies, both onscreen an off, but it also signals an increasing willingness to delve into painful personal territory. Both “The Stall” and “Play Place” read as if fueled by very personal frustrations, and they both succeed at making horror metaphorical without making it dry or preachy (in other words, it’s still good bloody fun).

“I’m Dreaming of a White Doomsday” (2013), which you should download now (on 12/24, Amazon has the collection it’s in for free!) to feel especially horrific for the holiday, is also apocalyptic, but like “The Stall,” the apocalypse involves slithery things more like a Lovecraftian End. “Doomsday” is both shorter than “Play Place” and more poignant, comparable to a quick, loving stab in the heart. It’s about a mother and son hiding out in a bomb shelter on Christmas Eve. Supplies are low, but braving the apocalyptic landscape outside might be worse than simply ending it all themselves. Meanwhile, the little boy insists that Santa’s on his way. And he is. He really is. But apocalypses have a way of changing everything, don’t they? I quite like this story: I don’t go for just any knife in my heart, but this one is exquisitely wrought, if perhaps a little abrupt at the end. You might want to give it a look before you read what Lombardo has to say about it in our interview (what he says is better than anything I can put here).

I’ll close by saying that I notice a tendency in both “Play Place” and “Doomsday” that, especially since “Doomsday” could be the next Reel Splatter film, I hope Lombardo investigates with his camera. In his prose, Lombardo seems to have a penchant for amazing tableaux, something at which film directors like Francis Ford Coppola and Ridley Scott particularly excel. Without getting into spoilers, I’ll say that “Play Place” includes two portrait-like images, one set in the the ball pit, and one involving the Play Place’s plexi-glass porthole at the end, that would work beautifully on film, but I haven’t really seen Lombardo the director play with that type of tableau/portraiture yet. Similarly, I will close with what could become an iconic image in the annals of American film:

“Cold. Darkness. The wind howls like a banshee. Clumps of ash fall like snow from swollen clouds. A lone figure trudges through the desolation. His leather boots sink through the knee-deep soot. The red of his suit is stained gray and matted like a mangy dog’s fur. A gas mask obscures his face and he is hunched under the weight of the large sack he carries on his back. He is a thing of myth, of folklore. Born from the innocence of a child’s imagination. He has many names: Saint Nicholas, Father Christmas, though he is known to most simply as Santa Claus.”

Merry Christmas, y’all.

Comments are closed.