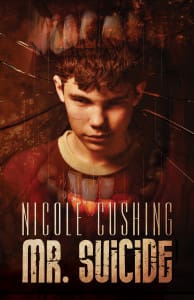

Mr. Suicide is the best new horror novel I have read in years, and Nicole Cushing accomplishes the coup through immersion in the perspective of a psychopathic child on a quest to erase existences, maybe those of family members, maybe his own. The book is not for readers who are easily offended or who don’t like their world-views challenged by sickening, disturbing thoughts and images, but if you like literature that turns the world upside-down, shakes out the bad parts, and puts them on display for all to examine, you must read Mr. Suicide NOW.

Mr. Suicide is the best new horror novel I have read in years, and Nicole Cushing accomplishes the coup through immersion in the perspective of a psychopathic child on a quest to erase existences, maybe those of family members, maybe his own. The book is not for readers who are easily offended or who don’t like their world-views challenged by sickening, disturbing thoughts and images, but if you like literature that turns the world upside-down, shakes out the bad parts, and puts them on display for all to examine, you must read Mr. Suicide NOW.

For an asynchronous interview with Cushing (which features more of her great writing), visit the Guests’ page. For an explanation of why I love this novel, keep reading. As always, nobody bribed me to do this work, and though I’ve met Cushing, we only know one another through the writer-convention circuit.

When I first saw the novel’s second-person prose, I scoffed. I’ve read many books that try sustained second-person narrative, and they almost all fail, but Cushing succeeds because she does not hesitate to give her “you,” the novel’s perspective character, both universal appeal and cringe-inducing repugnance. In solitary moments, he meets Mr. Suicide, who goads him to off himself, and sharing the character’s perspective, you aren’t “sure if Mr. Suicide [is] just in your head” (9). At least initially, the second-person writing processes the wilder experiences of the character in a familiar-enough manner to keep reader and character intimate: his thoughts might really be your thoughts, if you confronted the same things he did. His seemingly rational reactions to what seem like irrational circumstances could make others of “your” feelings familiar, too, especially if you’ve had your own dark moments, contemplating suicide but soldiering on: “You lived on, mostly out of spite” (25). These more common feelings help less common feelings slide by, such as the early admission, “The first person you wanted to kill was your mother” (2). Well, if you were the type of person who wanted to kill, the first person you knew was probably your mother, so she’d be a candidate, right? So if you accept at the outset that you’re a psychopath, all of these thoughts make sense, right? Cushing creates psychopathic intimacy that pushes thought beyond limits of traditional rationality.

Beyond rationality, the boundaries of conventional ideas and behaviors blur, which Cushing acknowledges by making a major destination in her psychopath’s quest a fetish club called The Border Crossing. While most readers will find the club and the in-novel magazine it echoes, Perfect Monsters, plenty shocking, the most shocking border crossing Mr. Suicide displays might be the ease and seeming naturalness with which the central character conflates sex and murder, how as you move through the story, you feel “the urge to kill infuse itself into your urge to fuck” (129). The aim of sex becomes destruction, preferably the destruction of someone vulnerable, regardless of the someone’s genitals (orifices can always be created). Having superficially consensual but still predatory sex with a girl who suffers from significant disabilities, the perspective character reflects, “Fucking her was like fucking disease, itself” (82). Fucking, itself, becomes disease: the psychopath taints everything you with pathology.

The diseased mind you inhabit in Mr. Suicide inhabits, in turn, a diseased world. While the degree of his psychopathy is difficult to place in proportion to anything, it is literally and figuratively at home with his mother, whose abusive attitude has roots in “some bizarre twist… Christian dogma [that] managed to coexist with all the vulgarity in her head” (3). Cushing puts social hypocrisy on display throughout the novel, especially when she turns to the topic of mental illness, which many characters in the novel perceive as the problem with her central character but about which no one responds with compassion or even appropriate containment. When a cop comes to the kid’s house after he commits an early act of violence, the cop berates him and asks him to explain his behavior. “‘And do not tell me you have a chemical imbalance,’” the cop says, “‘Jesus Christ, if I hear another teenager say they’re bipolar-schizophrenic this week, I’m going to go bipolar-schizophrenic, myself’” (53). The cop’s attitude allows the psychopath, rightly, to dismiss him as one of many “bullies,” and it also shows how the common misuse of terms such as “bipolar” and “schizophrenic,” two different conditions with strong genetic components into which people do not simply “go” as a result of common stress, leads people to ignore serious problems. The simultaneous scapegoating and ignoring of mental illness enables violence. The novel does not blame or preach; it shows ugliness through searing prose.

Exposing ugliness through riveting, dark passages becomes Mr. Suicide’s main business, a business that makes the book almost impossible to put down (I read most of it in a single sitting). Why?

“If you opened your eyes to the best parts of ugliness, then you had answers” (127).

Some of those answers appear in the ugliness the main character finds on the streets of Louisville, Kentucky:

“There was a certain psychological refreshment you found in abundance. There were other people walking around, too. A good dozen of them, treading the sidewalk either alone or in pairs or in trios. You’d never met any of these people before, but just by looking at them you felt a strong kinship… Like you, they were people who lingered in the dark…

Many also had backpacks. Many, also, had escaped the chains of hygiene. Some of the women looked like whores. Some of the men looked like sleepwalkers. Occasionally you saw an infant among their number and felt jealous that it would, from its earliest days, get to revel in the sort of life you’d had to wait eighteen long years to participate in.” (100)

Opening your eyes to these details of street life—people who are disaffected, dispossessed, and otherwise at the bottom of the social hierarchy—might reveal appeal in disassociation from the hypocrites and bullies whose dogmas and misinformation foster the very violence that shatters boundaries. Tune in, turn on, drop out.

In a world full of ugliness, escape into darkness is appealing sometimes, and that is the lure of Mr. Suicide, as well as Mr. Suicide, “a Novel of the Great Dark Mouth,” as its subtitle proclaims. The novel is about, and is, a cage of unwanting. You may want to dissociate from the character whose mind you’re in, but you can’t escape having one thing in common with him: you do not want to be there. Dissociation is an unbreakable line of empathy to a psychopath, and Cushing uses it to tether you to horrors that swallow you, digest you, and, if you keep your mind open to the answers that ugliness offers, make you want the Great Dark Mouth to open again.

Comments are closed.