Highly readable and relatable, even as he freaks you out with taboo-breaking scenarios, Jason Nickey is here to discuss two recent extreme horror novellas, Rural Decay and Past Due: Rural Decay II.

Rural Decay

Jack Buckley always admired his father, even after he found out he was a serial killer. As Jack grows older, and he begins helping his father, he begins to develop an unhealthy obsession with him, an obsession that would send both of their lives crumbling into decay.

From Jason Nickey, author of Wreckage, comes a new story of extreme horror.

Past Due: Rural Decay II

While adjusting to a new work assignment in rural West Virginia, Jake Bailey begins to notice a strange man in a creepy yellow truck following him. As time goes on, the frequency of his encounters with this man continue to increase until, one day, he finds himself tied to a chair in the man’s shed. What follows is a nightmare beyond anything his imagination could conjure, and an outcome even Jake himself would never have expected.

From the mind of Jason Nickey comes another twisted tale of Rural Decay.

The Interview

Rural Decay

1. Sex and Violence. From a very early age, mostly thanks to his father Hank, Rural Decay’s narrator, Jack, associates sexual acts with acts of violence, and later in life he finds sex less satisfying when not associated with violence. How does connecting sex and violence relate to the “monstrosity” of Hank and Jack? Is the connection primal, insane, both, or neither? Should sex and violence be disconnected? Why or why not?

JN: Sex and violence seem to go together quite often, both in real life and in fiction. In the case of Jack, however, I see the connection as both primal and insane. He experienced his sexual awakening alongside the violence his father inflicted, which skewed his perception of both. While the two should absolutely be disconnected, the line that separates them was blurred for Jack because of his upbringing and the violence he witnessed.

2. Masculinity. One of Jack’s early admissions is that his father was a serial killer but also his “hero,” in part because he “just emanated masculinity.” What does masculinity mean to Jack, and what, if anything, does it have to do with violence and killing? We’re discussing a story called Rural Decay: do you think there’s something particularly rural about this brand of masculinity? Why or why not? Do you think your book puts this brand of masculinity in a critical light? Why or why not? What is your personal definition of masculinity?

JN: I remember, as a young boy, being drawn to what most of society deems as masculine features on men. Facial hair, body hair, abrasive personality, etc. It wasn’t until later in life that I realized it was a sexual attraction. Men in rural areas are often more likely to carry these features, or at least carry them in a more rugged way. As I’ve grown older, I’ve realized that these features don’t necessarily define masculinity, but for this story, I was writing from the perspective of Jack through his childhood, so he’s not going to have an educated view on such a topic at a young age. I wouldn’t say this story is a critique on masculinity, but I think most boys at a young age will look at the men in their lives that fit the masculine stereotypes that society has created as a building block for what they’re supposed to be when they get older, even if it’s in a non-sexual way.

3. Misogyny. Men in Rural Decay (as well as its sequel) treat women as objects to be used for sex and violence and then discarded. Why do they have this attitude, and what does it say about the world they live in? Jack reacts positively to his father’s treatment of women, so readers don’t get women’s perspectives on the men or their behaviors. How do you think women would perceive Hank and Jack? Jack doesn’t objectify women completely—he identifies with women as they get fucked. Do you think Jack’s attitude toward women is fundamentally different from Hank’s? Why or why not?

JN: Sadly, men often treat women as objects in real life. It’s something we see happen on a regular basis, though not always to this extreme of an extent. In a way, Hank from RD1, along with Henry’s family in RD2, are a critique of men using women in such a way. Just like many of the men who do this in real life, we don’t always know the driving force behind it. In some cases, there are childhood events that lead to such acts, but there are also some people who, in my opinion, are just born monsters. It’s why many women, and some men, choose the bear.

Jack also sees women as objects, but not in the same way as his father. They’re a way for him to bond with his father, but also an obstacle in his eyes, as he wants to be the recipient of his father’s sexual violence. I think the women in the story would see that the same way. They would see Hank as a monster and Jack as a boy who’s lost and has his mind twisted by his father’s actions.

4. From Father to Son. Both Rural Decay volumes focus primarily on relationships and the unusual forms of love that make them work. In the first volume, the focus is on the father-son dynamic between Hank and Jack. What inspired you to write about rape and murder as father-son bonding, and how does that bonding relate to more typical father-son bonding? Hank tells Jack he acts on unusual homicidal urges, and Jack later thinks he inherited his own urges from his father. Where do you think the passing of murderous impulses from father to son falls on the spectrum from nature to nurture? Jack’s admiration for Hank turns into sexual attraction. Does this attraction stem from some pathology, inherited or otherwise, or might there be a sexual component to male bonding (kind of like Freud took some bad acid)?

JN: While sports are more common, I often see hunting as a father-son bonding activity, especially in rural areas. While not remotely comparable, what Jack and his father did together was a form of hunting, just taken to a much more extreme and twisted level. While there’s never been a case in real life of a serial killer’s child also becoming a serial killer (as far as I know), I thought that would be an interesting direction to take it in. It’s pretty clear early on that Jack is mentally unwell, even at a young age. To me, it’s quite possible that someone in this situation who has been subjected to the things Hank did could have their views of family bonding and sex skewed to such a ridiculous level, especially living in the isolation of a rural setting.

5. (Gay) Porn. While Hank is interested in women, Jack is interested in men, and like his father, Jack gets to act on some fantasies related to his interests. To what extent—considered in the broadest way possible—is Rural Decay about acting on forbidden fantasies? Reading parts of the book, I thought of common categories of gay porn on the internet. For example, very early on, Jack is excited by seeing his dad naked with an erection, the type of image he could find in a “Daddies” category. “Dads for Sons” and “Stepdads for Stepsons” are other common categories. Were you thinking of porn, particularly gay porn, when you created Jack’s sexual desires and activities? The book includes diverse eroticism. How do you want readers to respond, and can you provide any examples of responses you’ve gotten?

JN: I knew going into the story that I wanted it to be taboo. In my first collection, Static and Other Stories, there is a story called “My Father’s Eyes.” In this story, a young man discovers that his recently deceased father was a serial killer. After this discovery, he decides to try and follow in his footsteps. This felt like a very powerful story when I wrote it, and originally, I was just going to expand on that story some more. It was around this time that I realized, through all of the extreme horror I had read, it very rarely contained any queer eroticism, much less taboo queer eroticism. I wanted to push that boundary and give the reader something they haven’t seen done before. From that, this story was born. I took the father-son aspect of my original story and added the sexually taboo aspect. I personally found it easier to write such scenes by giving Hank features that I typically find attractive on a man. My goal with this was to make the reader as uncomfortable as possible, and from the responses I’ve gotten, I feel like I achieved that.

One last thing I’ll add is that I originally wrote the rough draft of this story about a year before I released it. I sat on it for a long time because I was a newer writer and was afraid of the accusations that may follow from readers who are unable to realize the author is not their story. Now that I’ve released it, the response has been quite the opposite. Not only have I not received any backlash (so far), but people seemed to appreciate something both twisted and queer delivered in what is mostly a heterosexual dominated sub-genre. I’ve even had many straight men tell me they loved this story, which is something that will never cease to amaze me.

Past Due: Rural Decay II

6. Rural Fear. Past Due: Rural Decay II offers more direct commentary on the rural dimension of the series, opening with comments about ways in which rural encounters are likely to be a little more intense than encounters in other areas. Do you think rural horror is intrinsically scarier than its urban or suburban counterparts? Why or why not? Other than the initial setup, which involves the narrator, Jake, driving around a large rural territory on business for the power company, why does the setting for Rural Decay II need to be rural? What is rural about the decay you depict?

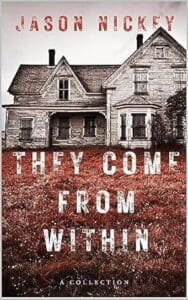

JN: The easiest way for me to answer this is to explain my job. I work as a contractor for a local power company. While I live in the city of South Charleston, my work area is often the rural areas of the surrounding counties. Doing this work regularly puts me in locations that, to me, are quite creepy. Remote locations where sometimes I’m probably the only person around for at least a mile, and let me tell you, that realization alone can sometimes get the mind wandering. There’s also the poverty I see in these areas: decrepit houses, yards filled with junk and abandoned cars, and residents that are rougher around the edges than the typical people you encounter. In saying that, it’s not so much that I feel a rural setting is scarier than an urban one, but it’s one that I’ve become more familiar with while working this job. It goes without saying that my job is a big influence on my writing. The places I’ve been while working this job have inspired the setting for many of my stories, including both Rural Decay books, Road Hazards, Don’t Look in the Trees, and selected stories from both Slush Pile and They Come from Within.

I want to close this question by saying that using these settings is in no way an attempt to insult or criticize folks who live in poverty or in rural areas. It’s simply just a setting that inspires me on a daily basis and one I’ve become familiar with over the last few years.

7. Humiliation/Infantilization. One of the most extreme horrors of the second book is the dehumanization Jake suffers while he is captive and immobilized. He has no choice but to urinate and defecate on himself, and then he feels humiliated when his captor, Henry, must clean him up like a “baby.” For the sequel, why did you focus on this type of violence, arguably a kind of psychological torture, as opposed to the more physical extremes of the first book? How do the types of victimization compare? Going from Rural Decay to Rural Decay II, you switch from the perspective of (primarily) a victimizer to the perspective of a victim. How did the writing experiences compare?

JN: While both Rural Decay books have a psychological aspect to them, I wanted to lean into that aspect more with this one. I wanted it to go beyond captivity but felt like going the torture route would be too much like other books that I’ve read. I decided to go the humiliation route instead because it’s one I haven’t seen done as often. It was a bit easier for me to write this one because I’m a more passive person by nature. Since the main character wasn’t participating in most of the violence being depicted, it was easier for me to put myself in his shoes.

8. Stockholm Syndrome or…? During his captivity, Jake learns about Henry’s abusive family and develops sympathy for him that turns into a form of attachment. Is this attachment genuine, or is it more the result of Stockholm Syndrome, the sense of a positive psychological bond that sometimes forms between captors and captives? What draws Henry to Jake? What makes Jake receptive to Henry? How do you expect readers to feel about their relationship?

JN: This is a two-part answer that is heavily based on some of my own life experience.

I’m a survivor of an abusive relationship. It’s a life I lived for about ten years. For myself, and many others I’ve spoken with who have also been in an abusive relationship, it’s like a form of Stockholm Syndrome. Your abuser or “captor” is someone you love, but also makes you feel trapped.

On the flip side of this, my current partner is also a survivor of an abusive relationship. That history was a part of how we connected early on. Working together to adjust to not being with an abuser, along with getting over the PTSD that can come from such a relationship was like a form of trauma bonding for the two of us, and we have a great relationship as a result of this.

I decided to take both of these factors and use them for the dynamic between Jake and Henry. Jake, like me, is an abuse survivor, so after seeing Henry being abused by his family, he grows compassion for him. I wanted both Jake and the reader to both fear and empathize with Henry.

9. Horror Story, Love Story, Extremes. The relationship and unusual love that Rural Decay II focuses on is between Jake and Henry. Would you call this book a love story? Why or why not? Unlike the cover of the first volume, the second volume’s cover doesn’t advertise the book as “extreme.” Is it extreme horror? Why or why not? How are love stories and horror stories connected? What do you want readers to take away from the extremes, horrific or not, that you visit?

JN: My goal with any story I’ve written is to bring something the reader hasn’t seen done before, or at least hasn’t seen as often. I do consider this an extreme story; however, I don’t see it as extreme as its predecessor. I do view it, in a way, as a love story built on horror, and that was my intention. To me, fear (horror) and love are the two most extreme emotions a human can experience. They’re usually emotions that are kept on opposite ends of a story, but I wanted to make them meet in the middle.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

JN: Links to my Amazon page, along with my bigcartel store for anyone interested in purchasing signed copies of my books can be found at https://linktr.ee/bibliobeard. There are also links to my socials there.

About the Author

Jason Nickey is a horror writer from West Virginia, where he lives with his partner and three cats. He focuses on short stories and novellas. His writing style ranges from general horror to extreme and everywhere in between.