The (Un)Importance of Politics in Records of the Hightower Massacre (2024)

by L. Andrew Cooper

If a book makes heroes out of people you’re inclined to dislike no matter what they do, and if the same book makes villains out of people whose views you at least partially share, you’ll probably see that book as pushing an agenda, preaching at you. On the other hand, if you’re pro-protagonist and anti-antagonist, the book might seem less didactic and more realistic.

Records of the Hightower Massacre assumes that LGBTQ+ people have a right to exist (as such), and it makes such people heroes in a struggle against rather nasty villains who assume LGBTQ+ people don’t have the right to exist (and act on their assumption). If you’ve got a problem with any part of LGBTQ+, the book will seem to have a “message” for you. If you don’t, the book will seem more like a mirror—of the funhouse sort, certainly—but it’s not trying to tell you anything you don’t already know.

What it is trying to do (and I humbly submit that it succeeds) is create an exciting, horrifying story out of the fact that people have in the past and might in the future act on the assumption that LGBTQ+ don’t have a right to exist. My co-author Maeva Wunn and I chose the future direction, taking an unspecified leap forward to a post-American dystopic city in what was the Midwest and a slaughterhouse on its outskirts that has been converted into the Hightower Course Correction Center (HC3). HC3 recruits desperate LGBTQ+ people, promising to put them on the cis-het “course” so they can find employment and survive, but they soon reveal that their methods include brutal psychological and physical torture as well as other “treatment” that makes mere murder look mild.

So, yeah, it’s obviously political, except the politics don’t matter much to what happens in the story, which is a sequence of escalating horrors as the alternating narrators, Ash and Aubrey, discover new depths of HC3’s depravity while gathering allies and learning to fight back. Maeva and I did not plan story beats according to political ideas; we structured a series of horrific mini-climaxes, each more gruesome than the last, leading up to the big bang at the end. Beyond what’s intrinsic to the premise, the only political bits I baked into the story, actually (I leave disclosure of any other hidden agendas to Maeva), don’t appear clearly until the denouement, but their purpose is to introduce ambiguity, not a moral.

You don’t need to have read Fredric Jameson’s The Political Unconscious (though it’s an awfully good book) to have encountered the idea that all stories are on some level political, that storytelling is a political act whether you want it to be or not. I agree with that notion, so I tend to smile and nod when anyone claims a piece of writing isn’t political. My point about Records of the Hightower Massacre isn’t that it’s an apolitical story if you look at it the right way—that makes no sense to me—but that it’s a story about people fighting to survive extreme horrors. Unless your prejudices make them unavoidable, think about the politics as much or as little as you want. Enjoying the ride is more important.

About the Author

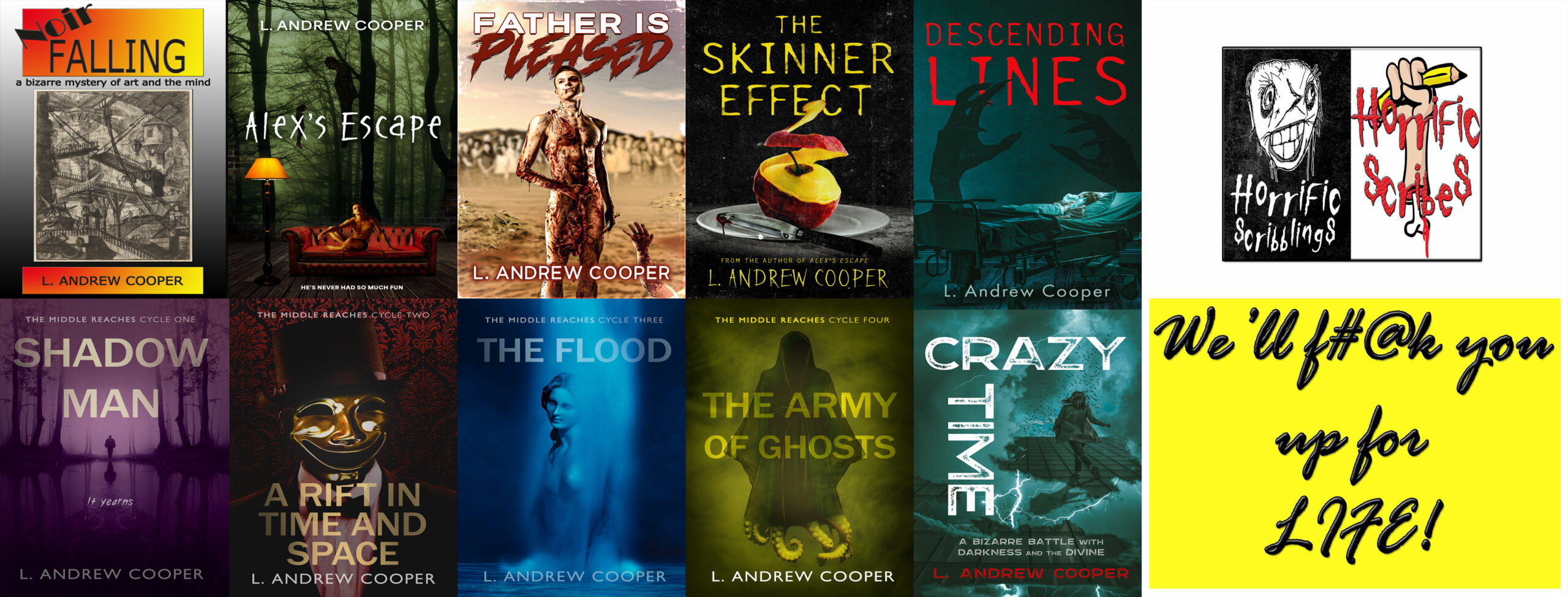

There’s enough about L. Andrew Cooper around here. Scroll down. Check the CV, Books, Short Stories, Screenplays, Links, About. You get the idea. It’s his site.