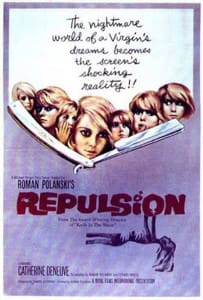

Look on the Internet Movie Database, and you’ll see a tagline for Roman Polanski’s 1965 film Repulsion that almost preempts interpretation: “A classic chiller of the ‘Psycho’ school!” Marketing-wise, the claim hits its target because Repulsion clothes “higher” art-house sensibilities in lower production values and in horror-genre conventions, just as Hitchcock decided to do with the film that he brought to Universal (home of the horror monsters). Like Hitch, Polanski uses black-and-white grit to showcase a story of a woman in distress that takes an unexpected turn involving two grisly murders in a space distorted by her psycho-logical state. Polanski even uses a beautiful lead whose sweetness misleads with innocence—and although Tony Perkins’s defiance of Robert Bloch’s vision of Norman Bates as an awkward and homely killer is unforgettable in Psycho, I don’t think many would deny Catherine Deneuve as Carol in Repulsion (or as anyone at any point in her career) rivals Perkins with talent and circles him with her stunning screen presence. Her largely nonverbal performance, combined with her environment’s responses to her, conveys the psychological depth that Perkins and “mother” communicate by doing the police in different voices, creating misdirection and ambiguity until a solution may or may not appear at the end. (Beware continuing—here there be spoilers!)

Like much else in Hitchcock’s oeuvre, Psycho’s ending has received a great deal of commentary and debate, so to claim that the ending—the psychoanalytic revelation of the shared mind/body of Norma/Norman Bates resulting from a psychotic solution to an Oedipal struggle gone terribly awry—is unequivocally sincere would require proof and argument I am uninterested in providing here. However, the psychiatrist who shows up at the end provides this explanation, and taking it at face value is possible.

Repulsion, like Psycho, has a twist involving its main character’s mind, but its central psycho, Carol, doesn’t go out on a frenzy to claim any victims. She stays home, mostly having conflicts with herself; although Norma/Norman’s victims come to her/his motel and house like flies to a web, she/he still ends up coming after them, whereas Carol’s victims, both men, have to throw themselves at her, the first breaking into her apartment and the second attempting rape, before she attacks. Prior to these attacks, the film demonstrates that Carol is very reticent around men. She refuses a date; she reacts badly when her sister engages in a sexual relationship and brings a man into their shared space; she shows disgust when a man kisses her. Her initial demonstration of the film’s title, repulsion, seems to be a reaction to men, an allergy to heterosexual sex. Ergo, the pathology she exhibits in the film’s second half, as she lets her surroundings decay (she leaves out food and eventually corpses to rot, neglects her own hygiene, etc.), links to her aversion to sex, adding up in the end to what seems to be a sexual pathology, psychoanalysis’s specialty. A psychiatrist doesn’t show up with an explanatory key as he does at the end of Psycho, but, as Carol does emerge as a psychopath, the film adds up in a way that forms a lock that seems the perfect shape.

Two shots in particular support reading Carol as a psychopath. The first shows her walking past a car wreck on the London streets. Everyone stops to look but her. Her lack of interest and empathy suggests social disconnection, a disconnection echoed in the film’s final image, which shows her as a child in a family photo. Here, she looks in a direction opposite her family group, first seeming perhaps to look at a man who might be the source of her androphobia, but then, as the frame tightens around her, she appears just to gaze away, again disconnected from all around her. This reinforcement of her social disconnection suggests it has little to do with any traumas she may have experienced, little to do with the men who keep forcing themselves on her, and everything to do with a pathology that has followed her since childhood. Psychoanalysis often traces disorders back to developmental interruptions, and this film, made during a peak of pop psychoanalytic dominance, embeds psychoanalytic causality for Carol’s behavior. Ambiguity persists, so the explanation is not totalizing or necessary, but it oozes from the film’s celluloid pores.

It also appears in a tagline from the film’s poster-turned-DVD-cover: “The nightmare world of a Virgin’s dreams becomes the screen’s shocking reality!” Dreams, the province of psychoanalysis—check. Virginal-frigid-sex-phobic-possibly-queer-woman, the “problem” woman of psychoanalysis—check. Carol makes psychoanalytic interpretive “sense” in 1965.

Of course, she also makes “sense” as a critique of psychoanalysis from a feminist perspective. After all, the men she kills are both attackers. The first stalks her and breaks into her apartment when she refuses his advances, and the second, her landlord, returns her rent and expects payment in sex instead, which he tries to take against her will. In 2015, if not 1965, watching this film, I suspect she might be able to plead self-defense if she didn’t present herself as batshit crazy, which, unfortunately, she likely would, as, by the end of the film, she is seeing hands reach out of her apartment wall at her, which the film gives us no reason to believe is not happening… other than the bits of context I’ve provided that suggest an otherwise realist context in which she is crazy (in 1968, however, Polanski would use Rosemary’s Baby to show the dangers of not believing the woman everyone believes is paranoid and losing her mind in a confined urban space).

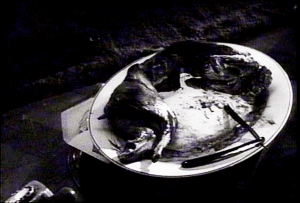

Before I close, however, I want to offer a third, more obvious interpretation for what Repulsion is about, and that is, simply, repulsion. To be more precise, it might be what Jean-Paul Sartre calls nausea. I will not allow myself to travel too far into the philosophy in Carol’s mother tongue, though, and will stick, with one exception, to a riff on Polanski’s title and say that Carol doesn’t have to be disgusted and repelled by men in particular. Indeed, while she does have a bigger problem with her sister’s new boyfriend because he’s the reason for her sister leaving her alone for days, she also has a problem with her sister leaving a rabbit in the refrigerator for her to have for dinner later, a rabbit that, like men and other items, she leaves out to rot. What do the rabbit and the men have in common? They are potential objects of appetite. If Carol is rejecting appetite, her rejection and the repulsion that drives it run deeper than sex.

The only place it might be for psychoanalysis is the place that Freud describes as beyond the pleasure principle, but even his heady concept of the “death drive” doesn’t get at Carol’s repulsion. Although she re-pulses, or reverses the drives of hunger and sex, she is not self-destructive. She begs her sister, a lifeline, to stay; she defends herself against attacks, vigorously. Her homicidal acts are not externalizations of a suicidal impulse. The re-pulse is not reducible to an im-pulse at all.

Alone, depressed, and alienated, Carol, a French woman in London, doesn’t want to let the outside in. After her sister leaves, she retreats to her apartment and tries to shut everyone and everything out. She has to eat but doesn’t want to. Her acts of resistance result in the decay of both her food and her body. She doesn’t have to have sex, but men try to force the issue. Her acts of resistance result in the decay of their bodies. Resistance ultimately appears—figuratively or literally, the film stops making distinctions—as cracks in her closed-off apartment’s walls, then hands reaching for her through the walls. The harder she tries to repel the outside world she wishes to reject, the more it presses in on her. As Sartre writes in the play No Exit, “Hell is other people.” Hell, a subject informing Rosemary’s Baby as well as Polanski’s The Ninth Gate (1999), is also a description of Repulsion, or maybe repulsion as that which Carol fails to accomplish.

What she wants is emotional autonomy. The desire may be impossible to fulfill, but that rock is where her dreams crash. If she is actually a virgin (the film, as opposed to the tagline, does not say as much definitively), sex may be a realm she defends more successfully than others, but that success may result from sex’s relative expendability among humans’ hierarchy of needs (an expendability psychoanalysts would loathe to admit). The madness of social isolation and repulsion may not be the center of Repulsion—the madness of company, the madness of ending up back in the world, may be the most repellent thing of all.

Comments are closed.