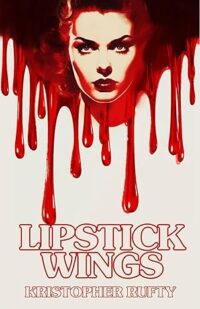

Highly skilled, experienced, and informed–with more than twenty novels to his name–Kristopher Rufty talks about one of his most recent titles, Lipstick Wings, a slasher in print and a heck of a good time.

Lipstick Wings

Marty Cantrell is an artist with a dark obsession. He follows women. But he’s not a stalker. He doesn’t harm them. They don’t even know he’s there, hiding in the shadows, watching them in their private moments like pieces of art displayed for only him to see.

One night, he saves Amelia Cole from the touch of a killer’s blade. By committing a good deed during one of his nightly escapades, he’s come out of the shadows that he’s felt secure hiding in for so long.

Now he’s ensnared in a psychopathic killer’s violent murder spree. He’s afraid of the darkness that had once offered him salvation. But as the body count continues to rise, Marty starts to wonder if he’s been the killer’s true target all along.

The Interview

1. Media I: From Novels to Gialli and Slashers to Novels. Examples of “body count” narratives have appeared in prose fiction and film since the early days of both media, but when people think body count stories these days, they tend to think of slasher movies, and a subgenre of prose fiction now exists in the spirit of film slashers. Lipstick Wings is in part a body count narrative—is it a slasher? Why or why not? More specifically—but this could be my obsessive bias—Lipstick Wings reminds me of an Italian giallo film, a horror-thriller originally inspired by books published in Italy with yellow (giallo) covers and a near progenitor of the slasher. Did giallo have anything to do with Lipstick Wings’s inspiration? Either way, what do you think of this tradition of storytelling about psychopaths and murder circling from prose to film and back again?

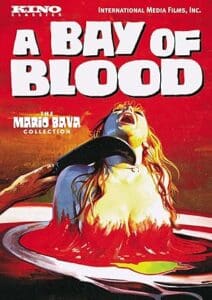

KR: Giallo movies were a huge influence on Lipstick Wings. I’ve adored them for years from way back in the VHS days, renting horribly cut versions with different titles. In the early days of DVD, a friend of mine was the first I knew to own a DVD player. He started ordering uncut giallo movie after uncut giallo. I’ve watched them pretty much consistently since then. Their style, the way they’re framed and filmed, and the music are just unique and darkly beautiful. There’s really nothing else like them.

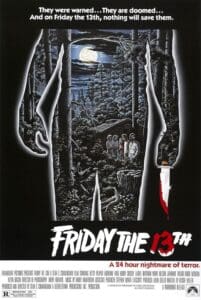

But I’m also a monster fan of slasher films. Friday the 13th was the movie that introduced me to horror at a very early age and springboarded me into wanting to create my own stories. Slasher movies are now my favorite horror subgenre. I love them all from backwoods slashers to college slashers.

I think that Lipstick Wings is a slasher, for sure. But it is also my love letter to giallo and those 90s sleazy thrillers that would come on Cinemax on Friday nights or Showtime on Saturday nights. I was too young to watch them at the time, so I was sneaky and did so anyway. There were a lot of good quality films from that subgenre of sleazy slashers that left their mark on me.

It’s great to see slashers and psychopaths in books a lot more these days. Growing up, I couldn’t ever find anything to read that was like the movies I liked to watch. I had yet to discover the Splatterpunks. And now there are writers, like me, who grew up hunting for these types of stories creating their own. I love it.

2. The Problematic Male Lead. Whether your main character, Marty, is a stalker might be debatable, but since he follows and spies on women, he’s certainly what a cop in the movie Body Double (1984, another possible touchstone for your book) calls a “peeper.” What he does violates women’s privacy and space. As a “hero,” he’s beyond flawed—he’s compromised. Why did you give him this trait? Do you expect readers to sympathize with him anyway? Why or why not? The description of the book above links his violation of women’s privacy to his proclivities as an artist. Does being an artist at all justify taking his voyeuristic impulses to the violating point where he takes them? Why or why not? Critics often see artists in books and films as stand-ins for writers and directors. Do you identify with Marty at all? If so, how?

KR: Body Double was another favorite of mine from my childhood escapades of watching movies I shouldn’t have been. Marty in Lipstick Wings is definitely flawed. I feel that he uses his artistic attributes as an excuse for his own issues. He knows watching these women is wrong. He hates that he does it but not enough to stop. He’s addicted yet justifies it with his creative nature and curiosity. To me, he’s in the wrong one hundred percent of the time. His little hobbies ruin lives and have ruined his own life as well. There is nothing redeemable about Marty’s hidden pleasures. That also made him, in an awful way, sort of fun to write. I don’t like writing about cookie cutter “heroes.” I feel the best heroes have flaws. Marty is an accidental hero in a sense. Wrong place, wrong time, but it opens a door to something he wasn’t expecting. But of course, lives continue to get ruined.

I don’t identify with Marty much at all. I do know a circle of people similar to those Marty associates with in the book. I’ve met people throughout the years of writing and the few years of working on independent movies that Marty becomes friends with from fetish models to actors and artists. They’ve become some of my closest friends.

3. The Female Killer. Although the killer’s facial appearance is (at least initially) cloaked by a hood, early clothing and other cues—as well as a victim certain she felt breasts when the killer’s body pressed up against her—make her female identity seem undeniable. Why did you decide to feature a female killer? Slightly more common in gialli, female killers are rare in slashers and other narratives featuring multiple murderers. Do you consider your female killer to be a challenge to your (sub)genre? Why or why not? Unlike the majority of male killers I’ve encountered in fiction and film (exceptions granted for TV’s Hannibal, 2013 – 2015), your female killer, “the silky coat flaring out to show sleek legs inside fishnet stockings and knee-high boots,” is quite sexy. Why? She hunts women. Is the woman-on-woman violence sexy, too? Why or why not?

KR: I’ve written about female killers before and always consider them to be some of the best to write. From slashers like the Sleepaway Camp series to Giallos with titles about killers in high heels, I’ve become fascinated with them. Also, those sleazy thrillers I mentioned earlier featured lots of female killers. I liked that. You’d follow along with the story, convinced one thing was happening, but would be surprised by the end. I feel that female killers have dynamics and range that are unmatched. I also like a revenge story with a female lead.

And yeah, the killer in Lipstick Wings wears fishnets and boots, which to me is very sexy. I think that stems from watching lots of heavy metal videos and those sleazy thrillers where the women often wore fishnets and tight, revealing skirts. Usually they had on heels, but it’s harder to chase down victims in heels, I would think.

4. Media II: Set Pieces and Cinematic Prose. The giallo, the slasher, and many other narratives noted for their body counts are often discussed for their set pieces, the detailed, usually in some way(s) gratuitous, scenes featuring the stalking and usually slaying of targets by the killer. The narrative sets up occasions for such scenes, and indeed, some would argue that such scenes are the purpose of such narratives. The story is secondary to the kills. I have seen “Jump to a Death” menus on DVDs. Lipstick Wings features elaborate descriptions of characters’ final moments. How much do you revel in these moments, and how much do you think readers revel in them? Do you think calling your writing in these moments “cinematic” is fair? Why or why not? Unlike slashers et. al, you don’t take the killer’s POV in your kill scenes but take victims’. Why? You often end chapters with deaths, the last things victims see, and the end of the chapter works like a cinematic cut to black. Do you see your chapter breaks this way? Why might you want or not want readers to have a cinematic experience in these moments?

KR: I don’t really sit down and plan how much to revel in death scenes. I come from a background of splatter films and books, so I naturally lean towards going “big” with the death scenes. They just go that route on their own, bloody, sometimes lingering, other times not. In Lipstick Wings, I did stay out of the killer’s POV intentionally because it adds to the mystery, I think. If we know what the person is thinking, we might not understand why or where it stems from or leads to. It’s sometimes scarier that way, too. I do love writing and reading stories that switch to the killer’s POV, but for this book, it works better without doing so.

I think you’re right about the death scenes ending the chapter, the final frame, so to speak. I didn’t really realize that I did that. That’s the story telling me that scene, as well as the character, is done. To me, I see these scenes as if they’re projected on a screen in my head. I’m not sure if other writers do this, but I just let the movie that’s going in my mind take me where it’s supposed to go. I see these flashy, gaudy deaths, and I try my best to describe them to the reader. I like cinematic scenes in books, showing and telling, that lead to bloody payoffs.

5. Southern Winter. Although you don’t emphasize it overtly, you set Lipstick Wings in the South (which, having grown up there, I claim the right to capitalize even though you don’t, which is also fine). Why? Do you think the Southern setting shapes the story—perhaps the moral perception of characters more on the sexual fringe? Interestingly, if I can trust my Kindle’s search function, you mention “the south” twice. Once is in relation to masculinity. Why do you think that is? The other time is in relation to the cold winter. Why did you choose a chilly Southern winter for your setting? What does the winter make possible for the scenarios you spin? What’s distinctive about your Southern winter atmosphere?

KR: Since I’m from the south and still live here, I tend to set the majority of my stories there. The Lurkers series takes place in the Midwest, but pretty much everything else I’ve written exists in North Carolina, where I live. But all of them share the universe. They all exist in each other’s worlds. I know the south really well, the pros and cons. I grew up here and have learned there are layers to the south, and some of them are rotten.

Winters here are never the same, always changing, and sometimes even during the same day. Sometimes we’ll have muggy winters, cold weather and somehow additional humidity. The snow, when it actually snows, never lasts. But to me, there has always been something almost… sinister about the winter season. I’m not sure where that comes from, but a horror story set during the cold months just adds a darker touch to certain aspects of the story. Maybe it’s the gray skies or the skeletal trees or the sunsets that sometimes make the sky look like it’s washed in neon colors. It also feels lonely, bleak. And the characters can feel it mixed with their dreads and fears, freezing them on the inside as well as the outside.

6. Sound. On the subject of atmosphere—much of which is cinematic—you devote a great deal of attention to dialogue. You frequently develop plot through conversations, verbal exchanges that frequently become heated. Why? How do you find characters’ voices and express them differently through their speech? Speech isn’t your only attention to sound that builds atmosphere and tension. You often describe sounds, or the absence of sounds, as characters journey deeper into situations where danger might lurk, escalating to a visual reveal that is a shock whether or not the outcome is truly threatening. How conscious are you of this technique? What do you think makes it effective? Do you have particular strategies for engaging the senses in order to play on readers’ nerves?

KR: Sometimes it feels the best way to move the plot forward is through conversations. Not always, but sometimes. I like crime fiction, especially the older pulp titles. I love how development happens either through dialogue or private thoughts of the narrator that seem to be directed at the reader. It’s like the reader finds out about situations at the same time as the characters. I like stories like that, a journey with the writer, characters, and reader. More times than not, I don’t even know what the characters are going to say until it’s written in the moment. I’m not a pantser, meaning, I don’t write completely by the seat of my pants. But I leave a lot of room for the characters to lead me instead of the other way around.

And to me, sounds, or lack thereof, are pieces of the story that are just as vital as the visuals. Silence can be terrifying, especially the heavy kind of silence where you enter a strange unknown place, or you venture into an area you’re not supposed to be in. Silence means somebody could be listening, could be watching. Just out of sight, hidden in that dark corner where the light doesn’t quite reach. Sometimes that corner is empty, but what about those other times? It’s frightening and frays my nerves even when writing moments like that. I can feel the character’s dread.

7. Shame, Victims, Victimizers, and Fetishes. Many characters in Lipstick Wings experience shame or shaming. Amelia, after being attacked, feels “accusatory stares” and doesn’t “want to admit she was a victim.” Why does she feel this way? Marty, perhaps less innocent, questions whether he’s a “perv” while spying on Amelia and feels ashamed of the impulses he has felt his whole life. Is his shame parallel to Amelia’s? Why or why not? Marty has fetishes beyond being a peeper, and your book features other characters with fetishes and a fetish club as a major setting. What’s your interest in fetishes, and how do you think your book depicts fetishistic behavior and fetishism? Marty likes following women from a library. Is something wrong with a library fetish… a book fetish?

KR: I think shame is something a lot of us feel at some point or consistently, whether it’s warranted or not. There are times where a memory from my childhood of me doing something stupid just pops into my head and embarrasses me all over again. Things like that stick with us, or at least they stick with me. I think Amelia’s shame of feeling like a victim stems from a place where she doesn’t want to be judged or pitied by strangers. But mostly it probably is her way of avoiding having to talk about it to others, to relive the horrible things that happened to her for the benefit of people who just want the details.

Marty’s shame probably dwells somewhere deeper, in a darker cellar somewhere in his mind. It’s the mutant offspring that’s locked away because it’s a reminder to him that he’s hiding something from everybody else. And if they knew what he kept in that cellar, that his dirty secret was being a voyeur and peeping on women, they wouldn’t approve of it, much like others wouldn’t approve of that ugly thing that’s chained in the basement, out of the light and away from prying eyes.

But book fetishes rock! I think all of us writers/readers have a fetish of sniffing book pages. I know I do. I’ve been busted at bookstores by other shoppers taking whiffs of the printed words, only for them to nod at me in an understanding, almost encouraging way.

8. Media III: Frames of Reference. Characters in Lipstick Wings often make sense of their violently changing world through references to fiction in print, film, or television. Victims-to-be think about their enjoyment of horror movies, Amelia makes sense of a police detective in relation to crime dramas, and so on. As you wrote, how much did you think about how much your characters think about other fiction? How typical is this referentiality—is it a standout feature of your characters’ world? A general feature of the entire world? What homages might your story make to others (beyond the ones we’ve mentioned)? What’s the importance of referentiality?

KR: I think a lot of us would do the same thing. A lot of our frame of reference for matters of horror-like distress comes from fiction in print or film. Let’s say I’m traveling on a rural mountain road that’s surrounded by acres of thick woodland, and I see a free gift that was left in the middle of the road, wrapped in a pretty bow. Now, the horror fan in me will remind me that movies feature situations similar to my current one, that getting out of the car to open the gift is probably a bad idea. That it might just be in my best interests to turn around and go back the way I came. Without the horror fiction to reference, I’d probably get out of the car and thank the Heavens that somebody left me a present, only to find a severed head inside or have it blow up in my face.

9. The Violence Quotient. I’m a terrible judge of such things. How violent is Lipstick Wings? I see you’ve got a story in a Splatterpunk Award-winning anthology, Fighting Back, and a Splatterpunk Award-nominated book of your own, The Devoured and the Dead. How does this book compare to your others, particularly in terms of violence and gore? I keep trying to wrap my head around this “extreme” thing. Is Lipstick Wings extreme? Are you extreme? Due to the sex and violence, who should read Lipstick Wings? Everybody? Nobody? Are people too uptight these days? Why or why not?

KR: Compared to some of my other books, Lipstick Wings might be considered a bit tame, but I hope the story is intriguing and pulls people in. It’s violent, for sure, but I’ve written others that are packed with the gruesome stuff. But it could probably still be considered extreme. I don’t sit down with a checklist of things to add to a book for it to be considered as a particular genre book. I just like to write the types of things I like to read. And I have fun. If I’m not having fun doing it, it’s probably not a story that needs to be told. I enjoy writing stories so much. It’s something I have done since I was a little kid and will keep doing for as long as I’m able. Even if nobody ever reads it, I’ll keep writing. I wrote stories for several years that nobody but me read, and I could do it again if I had to. I love it.

I’d read Lipstick Wings with a smile on my face. It kept me guessing while I was writing it, and I love stories like that.

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

KR: My website is www.kristopherrufty.com. It has a direct link to my webstore on the main page where people can buy signed books. The website will be getting a facelift very soon. I’m also on Facebook, Instagram, Bluesky, Threads, and TikTok.

Thank you for having me on! I appreciate you.

About the Author

Kristopher Rufty lives in North Carolina with his three children and pets. He’s written over twenty novels, including All Will Die, The Devoured and the Dead, Desolation, The Lurkers, and Pillowface. When he’s not spending time with his family or writing, he’s obsessing over gardening and growing food.

His short story “Darla’s Problem” was included in the Splatterpunk Publications anthology Fighting Back, which won the Splatterpunk Award for best anthology. The Devoured and the Dead was nominated for a Splatterpunk Award.

He can be found on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. For more about Kristopher Rufty, please visit: www.kristopherrufty.com