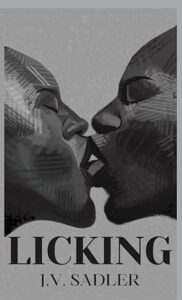

An emerging author with a strong sense of the unnerving and the uncanny, J.V. Sadler discusses her debut collection of short stories and poems, Licking.

Licking

J.V. Sadler’s first collection of short stories tiptoes through the waking and unconscious worlds. Take a peek into the upside-down world of Licking. Transcending reality, these stories integrate a diabolical twist into the mundane. In the title story, a couple’s hopes for a baby turn sour; “The Baboon” is a story of self-deprecation gone wrong; in “Unafraid” a woman will do anything to overcome her fears; eavesdrop on a dysfunctional family in “Family: Dinner;” a crowd struggles to save a dying woman in “Almost;” and many more twisty stories will have you questioning the everyday hustle and bustle.

The Interview

1. The Nightmare-scape. In your introduction to Licking, you write that you use your nightmares as the basis for much of your work. What is your process for transforming dream into fiction? You also describe your nightmarish work as different from a lot of horror fare—other than foregoing the usual boogeymen, what elements, particularly stylistic elements, set it apart? You mention that your work leans, at times, toward the surreal. What are examples of surreal moments that you can share without spoilers?

JVS: To turn my dreams into fiction, I must first journal about my dreams. I write dreams that interest me down on paper and try to decipher if there is a more profound meaning to them. I usually have the key scene from the dream and write around that scene. For example, for “The Decrepit Ones,” I had one key scene in a bathroom and had to figure out how to start and end it.

Licking, while leaning into surrealism, also seems to dabble in magical realism. The stories are set in the mundane world but then are invaded by horrific elements. I ask readers to forego the boundaries of logic and lean into the freedom of possibility. With just minor tweaks in the physics of the real world, these stories could happen. I believe this is what sets Licking apart from other horror—criss-crossing between the imaginary and the real.

Much of my writing is inspired by the Surrealist and Dadaist movements. Some moments in Licking that dip into surrealism include the struggles of Jaina in “Yappy.” Due to an unfortunate condition, she can no longer stand up for herself, which puts her in miserable situations. Or the nightmarish museum under strict rule in “The Decrepit Ones” has visitors’ own universe superseding the expectations of what a “regular” school field trip should be like. These stories have readers questioning, “Is this really happening? Or is it all a dream?”

2. Licking and Ingestion 1. In Licking, both the poetry and prose, licking, tasting, and consuming people can be a horrific act of revenge, but it can also be intimate, erotic, perhaps even transformative. How would you define “licking?” Does the act change meanings from poem to poem, story to story, or does it have an overarching significance? Why do you portray the consumption of others, literal or figurative, with such intimacy?

JVS: “Licking” is a perversion, a violation, a crossing of boundaries… I intentionally wanted readers to feel the same dirtiness, ickiness, and wrongness I had when dreaming of some of these stories. In Licking, not only are the characters experiencing being “licked,” but the reader is as well. The collection is a sensory experience like stepping in liquid with socks on or having sticky hands without knowing the origin of the substance.

3. Entrapment 1. In “The Decrepit Ones” and “Family: Dinner,” you portray disenfranchised characters facing institutions (in the former, literally a museum, and in the latter, the patriarchal family) that ensnare them, institutions with horrors they must fight against lest they be consumed. In the former, the institution seems to be powered by white privilege and aggression, and in the latter, the institution seems to be powered by male privilege and aggression. Do your stories offer a conscious, systematic critique of institutionalized injustice? If so, what makes horror stories useful for such critique? If not, how do you think such critique sneaks in?

JVS: What is more horrific than real, systematic, institutionalized injustice? What’s more horrific than colonization? Genocide? Cultural erasure? I believe horror is the perfect medium to showcase injustice. Because the stories in Licking are so open-ended and “up for discussion,” these critiques do sneak in. In the other stories, the injustices may not be as pronounced as in, say, “The Decrepit Ones,” but they still offer a deeper analysis of present society.

4. Facing Fears. In “The Baboon” and “Unafraid,” the act of facing one’s fears seems to me to be both triumphant and tragic. Do you agree that it’s both? If so, why does standing up to bullies (in the former) or actively conquering phobias (in the latter) slide toward negative extremes? Do you think a woman finding strength also risks losing her place within humanity?

JVS: To face one’s fears is to finally experience freedom but simultaneously to escape the safety that fear has to offer. There is a safety in keeping the unknown unknown. There is a safety in looking at the world through a fearful lens so that one is never disappointed, taken by surprise, or bruised. When you let go of fear, you are also susceptible to all that I’ve mentioned. There is a saying along the lines of “Do what’s right even if it’s not easy.” In these two stories, both characters achieve liberation even if it means facing those negative extremes.

I think a woman finding strength is an act of rebirth. But births are catastrophic. There’s blood, pain, and crying during a typical labor. It’s quite poetic, isn’t it? Finding strength isn’t some cutesy frolic through daisies, it’s a dirty trudge through garbage to get to the other side, which is personal liberation. A woman loses her/their place in humanity in that “the place” is held for those who conform. “The place” is held for a woman who loses themselves in trying to fit that definition of what a woman should be. To break that norm is to openly reject that place and say “I choose my own place” even if it means disaster. A fearless woman is, seemingly, a wonderfully disastrous thing. I love it!

5. Phoning Fears. “Almost” and “Yappy” involve horrors that unfold—in the former, with some dark humor—at least in part due to people’s infatuations with their phones. Is technology more a source or a catalyst for the horror in these stories? “Yappy” is particularly disturbing as the narrator is “reduced” through her phone-related experiences. Is her reduction victimization, or does she willingly surrender parts of herself through technology?

JVS: Having grown up in the digital age, I’m not one to knock all technology as some dark source for human destruction. But I do, however, warn that it’s not the technology itself but the way that it is used. In both stories, the technology can be used for good. For example, the phone can be used to save a dying woman in “Almost,” and in “Yappy,” it can be used to find love and romance. Instead, technology is abused by abusers—clueless onlookers and online predators.

6. Licking and Ingestion 2. The collection refers several times to the darkness inside people getting out, licking, and consuming them. What is this darkness, and where does it come from? Ought we to let it out? Are our relationships with ourselves nightmarish? Empowering? Erotic? All of these? None of these? Why or why not?

JVS: The darkness that I refer to is the shadow side we each have in us: those dark thoughts, those sad moments, the not-so-perfect parts of ourselves. We should let it out. Yes! But transmute such shadowness into something beautiful. For me, I let out my darkness in my writing. All of my sadness, strangeness, grief, anger, sorrow, et cetera I let out in a productive and non-harmful way through writing. I hear of these rage rooms where you pay to destroy things. I am a supporter of such rooms because they are a way to release heavy emotions without harming ourselves or others. We should be allowed to scream in the void sometimes.

The relationship we have with ourselves is a combination of a lot of things. We are whole beings with a range of emotions both light and dark, good and bad, dream-filled and nightmare-fueled. It becomes dangerous when we try to ignore the darkness because then it slowly but surely takes us over. Then, it takes charge. Lastly, it uncages itself in unsafe ways.

I like to call myself a darkness connoisseur, an academic of the darkness… I want to sit down and have a conversation with the devil itself so that I may better know it.

7. Entrapment 2. “Trapped, Chained” also features characters trapped in a very bad situation, characters forced to wonder, “What were they to do without their captor?” And their captor is “a typical Caucasian man, perhaps making him most dangerous” when compared to “a psychopath [or] a sociopath.” This story seems to say something about a socioeconomic system that creates a racial hierarchy that subjugates people while making them radically dependent on their oppressors… but I may be off the mark. What are you saying about relationships between captors and captives, and how does what you’re saying specifically reflect on the history of race in America?

JVS: That particular line about the “typical Caucasian man” has been a topic of much conversation. It’s become quite controversial. I want people instead to consider the line that comes after it: “He weaves through society without anyone ever doubting his character, his actions, his mind.” In our present-day society, the minds of marginalized folks, especially Black folks, are heavily scrutinized whether it’s society believing we are less intelligent or less sane. This scrutinization has even seeped into the medical field via historical and present-day malpractice and cruel human experimentation. On the flip side, those who have the privilege of writing history write themselves as the prime exemplars of the human: the better psyche, the better intelligence, and the less prone to be doubted.

Let’s take the zipping of a purse or the locking of a car door, for example. We’ve seen this trope countless times. Let a typical Black man walk past a purse-holding civilian or an unlocked car. That purse will be zipped and the car door locked. Let a “typical Caucasian man” do the same, and those cautions are usually not taken. In other words, his character, actions, and mind are not questioned in the same way that marginalized people’s are. This is why Ted Bundy could be called handsome and charismatic but Tamir Rice, a gun-weilding killer.

With “Trapped, Chained” I wanted to portray a sort-of reversed Stockholm Syndrome where the captor sympathizes with his victim and does not have the same apathy of the typical portrayal of a kidnapper or serial killer. As a person with mental illness—specifically bipolar disorder—it’s disheartening to see the sole depiction of a killer be that of someone with a mental illness. I thought to myself, what if he was perfectly sane but for some reason got a kick out of kidnapping while at the same time disappointed in himself and empathetic toward his victims? I want to explore this further in my future writings.

8. Licking, Last Words. The penultimate tale in Licking is “Licking,” in which the darkness inside mentioned in other pieces threatens to take the form of a baby, bringing back the darkness of family from “Family: Dinner.” Do you think the book locates something horrific within the family and, more specifically, reproduction? If so, what is it? If not, why does so much darkness seem to gather around familial ties? And as for ties—the final piece in the book, “I Licked You,” seems to be a farewell to the reader. The title has at least two meanings. What do you think this farewell says about the relationship your book establishes with its reader? What should your reader expect from the experience of getting licked?

JVS: There certainly is darkness concerning familial ties. In our present-day Western society, we seem to put more emphasis on the biological, nuclear family unit than on the created or found family. The nuclear family replaced the concept of the village and replaced what was a community with a heteronormative father and mother. The nuclear family is a Eurocentric concept that overrode those of specifically Indigenous American and Indigenous African communal societies. The loss of such a support system, I believe, is very sinister. It places the burdens of raising and rearing a child on the hands of two individuals rather than a whole community. In both stories, the families could have had a better outcome if surrounded by community rather than just a single-family unit.

The end piece, “I Licked You,” is one of my favorite pieces. I love fourth-wall breaks, but this fourth-wall break is a sensory break as well. “I Licked You” is the end of an experience which is the “Licking.” The book establishes an intimate relationship with the reader. Yes, it is erotic, it is dark, it is off-putting, but I hope it will be, at least cautiously, welcomed. I want the reader to sit down after being “licked” and take time to think. How did you feel? Did you just read the words, or did you experience the words? I want the reader to be able to sit with their own darkness for a while and wave to it.

9. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

JVS: I have a linktree (https://linktr.ee/jvsadler) where you can find all the links to my book, my website, and other interviews! You can buy Licking in paperback, audiobook, and e-book on Amazon (https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CSWPVWNZ)

About the Author

J.V. Sadler is a Cincinnati native, writer, and poet. Sadler specializes in speculative fiction, horror, sci-fi, dark fiction, and surrealism.