An accomplished horror author with literary and transgressive edges, Michelle von Eschen discusses her new collaboration Motel Styx and her recent story collection Old Farmhouses of the North.

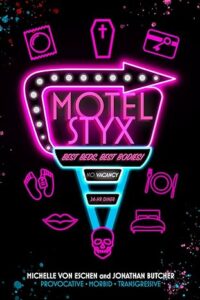

Motel Styx (with Jonathan Butcher)

Tucked away in the Chihuahuan Desert lies a motel unlike any other…

Fueled by online trends, a shift in the American zeitgeist has led to the instatement of the Lazarus Act, legalizing the “recreational use” of human corpses.

Ellis Mercer, recently bereaved, embarks on a secret mission to America’s first “necrotel” to recover his wife’s remains before her corpse and his memory of her are desecrated by the motel’s twisted membership.

As he uncovers the murky inner workings of Motel Styx, evading its suspicious staff and encountering a wild array of death-obsessed guests, he will be forced to face an unsettling truth: there is more than one way to define love.

Motel Styx is an explicit, disturbing, witty tale about lust, loss, and the last taboo.

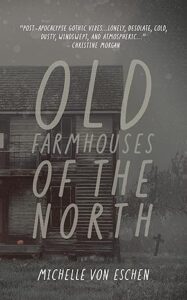

Old Farmhouses of the North

Beyond the borders of a barely civilized and struggling population, the barren fields of the North stretch into oblivion. Old, abandoned farmhouses, crumbling in a million tiny ways, stand on silent watch over the emptiness.

Old Farmhouses of the North features ten tales of quiet, literary horror exploring the predators and plagues of the human condition. Called “darkly poetic,” “haunting,” “emotionally crushing,” “enthralling,” and “stellar” by readers.

Spend a dark night in a pumpkin patch in “Noche Oscura,” search for a different kind of buried treasure with “Butcher and Shaw,” expect the unexpected in “What to Expect When You’re Expecting,” enter if you dare “The Bug House” … all of this and more from the bleak yet beautiful landscape of Michelle von Eschen’s mind.

The Interview

Motel Styx

1. Normalized Degeneracy. The world of Motel Styx has at least partially abandoned the taboo against necrophilia, but with constraints—consent, for example, is still important, and necrophiles are still supposed to respect the taboo against cannibalism. Why, in your fictional world’s logic, has the taboo against necrophilia started to fall? In the real world, assuming matters related to health and hygiene could be handled, should we have a taboo against necrophilia? Why or why not? If the taboo against necrophilia is a disposable construct, what about others, such as taboos against (again) cannibalizing the dead and against incest—could they be disposable, too? Why or why not?

MvE: In this world Jonathan and I created, which references at least one occurrence in another author’s work related to the criminal acts of necrophiles, an understanding is reached at a federal level that will reduce crimes against the dead by allowing for necrophilia in a controlled environment. This is much like legalising weed and taxing it. Safe access and monetisation is a win-win for all involved. I think in the real world we shouldn’t have a taboo against necrophilia anymore because we understand so much more about death and disease than we did in ancient times. We are also not governed by religion (which has larger groups objecting to sex with the dead), so concerns about afterlife and such shouldn’t hold weight. If you don’t agree with necrophilia, don’t do it! What is between two consenting adults should be fine as long as no one is hurt. Both cannibalism and incest can have pretty unwanted consequences. Prion diseases with cannibalism and birth defects with incest. One could argue that diseases can be contracted with a rotting body, and I think that would be a good argument for maintaining programs around necrophilia rather than a law that just legalises it.

2. The Zealots. A crowd of protestors—identified variously as Christian zealots, freaks, and hypocrites—stays near Motel Styx, decrying what goes on inside and waving around posters about the horrors of necrophilia. Do you intend the opposition to the “necrotel” to seem like idiots? Why or why not? To me, they seem a lot like extremists who protest outside clinics that perform abortions and harass women as they go inside. Do you intend a parallel with extreme anti-abortionists? Whether or not you do, what would such a parallel add to the story? How might a necrotel be like a clinic that performs abortions?

MvE: I certainly never intended to make them look like idiots. They are viewed through the eyes of people who look down on them and are, therefore, described in ways less than desirable. I can absolutely see the parallel between protestors outside Motel Styx and those outside abortion clinics, purely because the root of the protests stems from religious conviction and the activities of those using services at both locations are in direct conflict with religious tenets. Both types of protest seek to not only send a message, but to disrupt business operations.

3. “A type of torture where the victims don’t scream.” Some visitors at the Motel Styx find one attraction of sex and other activities with the dead to be the interaction with a human body that doesn’t talk back, resist, fight, or do anything but submit. They can treat corpses like the objects they fantasize other people, especially women, could be for them. To what extent does Motel Styx use necrophilia to reflect on pathological relationships between (or among) the living? Not to yuk anybody’s yum, but what kind of person wants to have sex with someone completely submissive, completely objectified, even to the point of unconsciousness and immobility?

MvE: One of the things I aimed to explore in Motel Styx is the motel as a microcosm. Many of the predilections we find in the larger population have their place within the walls. This includes interpersonal relationships and sexual tastes. Jonathan and I also mention the aspects of control and domination, which are common reasons why people are attracted to necrophilia. In relationships with the living, those with these types of tendencies don’t fare as well because, as you mentioned, they can be rejected, fought against, and denied. These same people might turn to rape as a way to both exert power and to achieve sexual pleasure. They might use Rohypnol to incapacitate. In Motel Styx, so-called body donors give lasting consent and allow a legal outlet for what would be otherwise cruel behavior. It’s difficult to get into the mindset of someone who would want this type of access to a body, but that doesn’t make it any less of a real thing. Statistical data are inaccurate because many who feel these urges are not open about it due to taboo and legalities.

4. Love is Strong as Death. As I mentioned during our correspondence, my favorite characters are probably Linette and Alfred, a mixed couple, one living and one dead, who stay at the Motel Styx. They’re gross, but they’re also kind of cute. Also sad. Linette has trouble letting go; so does Ellis, your main character. What does Motel Styx say about grief, and what inspired you to express ideas about grief in such a macabre fashion? For that matter, as Linette and Alfred may be a spot of true love in the middle of lots of death, what does Motel Styx say about love?

MvE: I’ve lost both of my parents, many extended family, and quite a few friends. Everything I write is about death, and many of my stories were born out of loss. Death is also something I fear, which is a common fear, and so I suppose exploring it through story helps take away some of that power. Over the years and the losses, I’ve been able to process my grief through fiction. As for love, it can be just as complicated as death. Just as we all grieve differently, so do we love. Linette’s and Alfred’s story was important to include in order to highlight that necrophilia, like love in general, takes many shapes. Those with this paraphilia aren’t all grave-robbing, sex-obsessed, perverted people. Sometimes all one needs is a quiet room with two chairs, one for them and one for their true love. It’s enough for her to be in the same place as someone who she feels represents something she lost, but wasn’t ready to let go of. I think it is one of the hardest things about life, loving mortal beings.

Old Farmhouses of the North

5. Housing Ideas. Old Farmhouses of the North is a well-designed collection, with stories that relate to each other plot-wise and, more often, thematically, and with farmhouses in a somewhat ambiguous North providing ominous locations throughout. What drew you to these decaying farmhouses in an imposing, infertile landscape for your diverse tales? The stories provide some details about where the “North” is, but how would you describe your “North,” its atmosphere and its people? How much, if it all, did you plan the collection before you wrote the stories? How did your old farmhouses come together?

MvE: I’m terrible at planning when it comes to my books. Things tend to take shape more organically, and it was no different for this collection. My mom was always pointing out windswept barns and old farmhouses, so maybe I’ve always been looking at them on family road trips when I was young and continuing to do so when taking her to medical appointments before she passed when I was in my late thirties. I like to think about a life the buildings once had, better paint, comings and goings, true purpose and warmth. To see them forgotten and abandoned, crumbling into the landscape, it all feels quite hopeless and temporary. They are the perfect backdrop for my bleak writing and the desolate atmospheres the stories evoke. I think I had several stories written before I realised they had somewhat of a common theme. I can’t remember how I came up with the title. If I had to choose on the map where ‘my North’ is, I’d say it is probably North Dakota. The people in my North are rugged, but weary, having experienced far more in each of their lives than any one person should.

6. Quiet Extremes? The blurb about this book (above) and your bio (below) describe what you do as “quiet, literary horror.” You do have a refined style that doesn’t emphasize chaotic screams and splatter, but at the same time, Old Farmhouses does go to extremes that make your work in Motel Styx not entirely surprising. In fact, Old Farmhouses, without sensationalism, includes necrophilia. Are “quiet, literary” and “extreme” mutually exclusive? How would you feel about expanding your label: “quiet, literary, extreme horror?” The bugs in “The Bug House” and the burns in “Firesick” get pretty nasty. How do you feel about writing the nasty bits, and do you see yourself going that far, or possibly farther, in future work?

MvE: My ideas do tend to be quite dark, but I don’t elaborate much when it comes to gore or violence (except in Motel Styx). I try to focus on the language and emotion behind horrible acts or events and how they impact people psychologically more so than physically. My husband writes extreme horror, and I think the word ‘extreme’ might give readers of my quieter work the wrong expectation. They won’t find what they are looking for. I do think I will revisit the more extreme side of the genre. I already have another idea that has some serious potential, and it will likely end up being a collaboration as well. I’m not sure if I’ll ever write anything more extreme with just my name on the cover.

7. Lyrically Present. In this collection, at least, you seem committed to present tense, first person narration. Why are you and other contemporary writers choosing the present tense—what does it offer writers and readers that more conventional, past tense narration doesn’t? Why might it be particularly good for horror? What about first person (which has deeper horror roots, Poe and such)—why do you choose it? How far “into character” do you get to produce your first-person perspectives? Which character from an Old Farmhouses story was hardest for you to write? Why?

MvE: First person, present tense feels most intimate to me and, in my opinion, is the best vehicle to convey emotion. The reader gets to walk in the shoes of the main character and experience their trauma in real time. I want readers to hurt a bit and to fear what is unfolding around them, but not to them. Honestly, I need to improve my characterisations and get to know the people I create much better than I do. I feel like it is one of my weaker points that I’ve only been able to know I need to improve based on feedback in earlier reviews and from my husband. He sees right through my use of characters as ciphers. I’m constantly trying to build better characters with backstory and depth. The most difficult character to write in Old Farmhouses was the main character in the opening story. He’s a villain and at that point in time I hadn’t written many.

8. Inside Out. Pregnancy and having children are significant issues in several stories, most obviously “What to Expect When You’re Expecting” but also “Butcher and Shaw,” “Clove Hitch,” and “Nancy Gone Wild.” “What to Expect” gets going like a riff on The Midwich Cuckoos (1957)—intentional?—but becomes exponentially nastier, “Butcher and Shaw” gets Satan involved, “Clove Hitch” presents a world where overpopulation makes reproduction a problem, and in “Nancy Goes Wild,” people attribute a young woman’s radical changes in behavior and appearance to pregnancy. Why do you address reproduction in these stories, and why does it so often appear in negative ways?

MvE: In the years prior to writing Old Farmhouses of the North, I underwent four major surgeries due to endometriosis. The disease makes uterine tissue grow elsewhere in the body, outside of the uterus, causing extreme pain, bloating, and other symptoms. 1 in 10 women have endometriosis, and medical science still does not understand what causes it. I lost an ovary and fallopian tube to scar adhesions after a cyst was removed from that same ovary. The right side of my abdominal cavity is a bed of scar tissue that still causes me pain. I don’t think I am able to have children due to the devastated landscape that is my insides. This might be why I write so much around pregnancy and reproductive trauma. It just makes sense as well that I would write so much about life-giving processes when I write so much about death. They are intimately connected and the end caps of our experience.

9. Delightfully WTF. Two stories are so delightfully strange that I want to give them special attention. Although surreal moments pop up throughout the collection, the best way I can think to classify “Noche Oscura” and “Because Father is Dying” is surrealist. Do you agree? Why or why not? “Noche Oscura” presents someone escaping a bad marriage and family pressures only to end up in a pumpkin patch, questing for his own proper pumpkin… what would you say this story is about? Would you call it allegorical? Why or why not? Why do you use an epigraph from Carl Jung? “Because Father is Dying” presents a family moving its members, including its dead, to a new house. What would say this one’s about, and would you call it allegorical? It strikes me as a childlike (but very disturbing) vision of the dead, death, and dying—were you going for that sort of perspective, or is the vision rooted elsewhere?

MvE: “Noche Oscura”was meant to be surreal. The ‘dark night of the soul’ is about confrontation of one’s self and the things that trouble us. I wanted to explore a man running from his troubles straight into them in an almost macabre funhouse presentation. It’s very much a reflection on purpose and on driving one’s own story, forming a life that one can be proud of, one not based on other’s expectations. To find your pumpkin is to find the way you want to spend your time on this planet. Carl Jung’s quote about the danger of the descent felt fitting in that there is no reward without risk. The end of the quote, which I didn’t include, notes that every descent is followed by an ascent. Truly, the only way out is through. I don’t see “Because Father is Dying” as allegorical. One day my twin sister pondered ‘what if we had to bury our own dead in our yards?’ and that got me thinking what would then happen when the number of dead needing a grave outnumbered the size of the yard. Well, you’d have to move to a house with a bigger yard! Just like when a baby is born and the family now needs an additional room in the house, as the dead increase, so does the need for more acreage. This story was me having fun fully considering a unique thought and also getting the chance to make a skeleton parade. 🙂

10. Access! How can readers learn more about you and your works (please provide any links you want to share)?

Website: https://www.whenthedead.com/

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/18935572.Michelle_von_Eschen

Tiktok: https://www.tiktok.com/@yourquiethorror_

IG: https://www.instagram.com/yourquiethorror/

About the Author

Michelle von Eschen (early works written as Michelle Kilmer) is an American author of quiet, literary horror. She is a lover of the macabre who prefers Earl Grey tea, October, people who say goodbye on the phone, and her dreams are so real she can’t figure out what has really happened to her. When she isn’t writing, she enjoys weightlifting, dark beer, web design, singing and playing guitar, and watching horror movies. She lives in the southwest of England with her husband, horror author Jonathan Butcher.