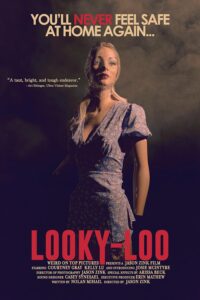

Adventurous and captivating director-writer team Jason Zink and Nolan Mihail discuss their forthcoming feature horror film looky-loo, and then Jason sticks around to comment on his short mockumentary “TAPEHEAD” as well as his soon-to-be-rereleased shorts anthology Night Terrors.

looky-loo

An aspiring filmmaker obsessively captures footage everywhere he goes, but his hobby takes a dark turn when he begins using his camera to stalk and film women. As he hones his craft, his crimes escalate from voyeurism to home invasion and, finally, to murder. looky-loo explores themes of voyeurism, obsession, and the power of images, with a chilling atmosphere and gritty, disturbing imagery that will leave viewers terrified long after the credits roll.

Releasing soon!

“TAPEHEAD”

A film crew follows a horror-obsessed VHS collector as he puts himself in dangerous situations to find his holy grail tapes. Available for you to watch now on YouTube!

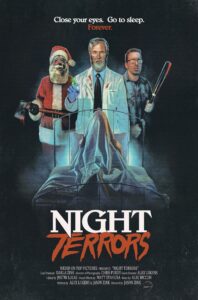

Night Terrors

A devious older sister fills her brother’s head with bizarre tales of terror, blood-soaked memories, and nightmares of perversion after finding out that she has to babysit and miss the party. Returning soon from Scream Team Releasing!

The Interview

looky-loo

1. Peeping Toms and Killer Cameras. You shot looky-loo entirely from the perspective of the voyeur/invader/killer’s camera, effectively putting most of the film into first-person perspective (POV, or point of view). Many horror fans think Halloween (1978) innovated the first-person, killer’s-eye-view (“killer-cam”) use of perspective in horror, but its use is of course much older, likely with examples going back to very early film but emerging spectacularly in Peeping Tom (1960), a film about a killer who not only stalks women with his camera but also kills them with a weapon he attaches to it. Of course, 1960 was also the year of Psycho, which contains a particularly famous scene about voyeurism and showering. looky-loo shows us showers more than once… how did these earlier films, or other films, influence your approach to telling your story? What do you add to the killer-cam tradition? Why do you think viewers are ready to be immersed in killer-cam POV for the run of an entire feature?

JZ: Truth be told, I’m not certain that they are ready… but this is where we’re at, and we think they’ll catch up. While films like Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer and Peeping Tom played with the killer as a filmmaker motif, we believe that we’re the first to commit to the format for an entire film, at least so strictly. And funnily enough, the idea for this project stemmed from a misunderstanding between Nolan and me. I had suggested making a low-budget version of Elijah Wood’s Maniac, but Nolan believed I was suggesting the killer was behind the camera filming his crimes. So, the idea came from both of us and neither of us simultaneously. Our team believes that this film places its thumbs in the eyes of true crime junkies and holds a mirror up to society. This, coupled with our homages and references to classic films like Psycho and Halloween, raises important questions about how we view violence and violence against women, especially.

2. Shared Perspectives. Film as a medium is, in some ways, all about voyeuristic pleasures. Does the man behind the camera in looky-loo (named “Looky-loo” in the credits) raise questions about sadistic voyeurism in the medium as a whole? As Looky-loo searches through women’s underwear drawers and otherwise indulges in voyeurism and home invasion, the viewer does, too, seeing what Looky-loo sees as a result of Looky-loo’s crimes. If Looky-loo is guilty for his voyeurism, does the viewer share in his guilt? Why or why not? Similarly, the viewer shares Looky-loo’s perspective on murders… any shared guilt there?

JZ: 100%. The film sort of begs you to turn it off, which we realize is a risky gamble. But we felt that it was important to make the film that Looky-loo would actually make, as opposed to a super entertaining horror film that a traditional filmmaker would create. It’s also important to put it on front street that this was planned as a trilogy early on. In the forthcoming sequels, we will stay committed to the structure, but our killer has gained more experience as a filmmaker. We’re daring audiences to come on the ride with us, and we hope they become more complicit and conflicted as the franchise moves forward.

NM: I think that most people are voyeurs to a degree. It’s the same impulse that drives people to read the tabloids or gossip about people they don’t really know. We love to know other people’s business. I think we kind of banked on that as a kind of lure to make sure people don’t stop watching as the action ramps up, and it seems to have worked pretty well.

3. Found Footage. Is your film looky-loo the same as the film Looky-loo is shooting within looky-loo? Yes or no, how are you twisting and/or expanding the found footage tradition in horror? The idea that the footage is “found” opens up a possibility in addition to viewers being accomplices along for the ride with Looky-loo: viewers could also be police, reviewing and judging the crimes. Do you think viewers police and judge Looky-loo’s illicit pleasures? Why or why not? If the film is Looky-loo’s, why does he include shots of his own editing process? A quirky question—Looky-loo’s shadow appears onscreen quite a bit, a very nice effect but one that seems hard to get with only natural light and the camera he’s holding. How did you get the shadow effects?

JZ: That’s an interesting question. We struggled a bit with how much we should commit to the premise. One of the festival programmers referred to it as “hard format,” which I think was pretty accurate. Other than the end credits, we never break the film’s conceit. So, while our film is ours, it feels like the killer’s movie. We anticipated some judgment or blowback from the audience, for sure, especially from women. We feel that the film is actually one for women, as opposed to the traditional slasher being from the male gaze. To be clear, the Looky-loo killer is not Jason Voorhees or Michael Myers, and we hate him. We were relieved to get a lot of positive feedback from the women in the audience at one of our screenings because we worried that they would misinterpret our message.

NM: At first, every editing room scene was essentially used like punctuation, just a device to break from one section and transition to the next. We weren’t sure what we were going to do with those at first. We had a long list of editing room activities, and some of them were really off the wall and didn’t make it into the final film. The idea of him including shots where he’s editing his own movie was compelling to us, because we saw that as almost an act of verification; no one else can take credit for this film because, look, here he is cutting the thing together. Looky-loo doesn’t want anyone to question the veracity of his work.

The shadows were all accomplished with natural lighting and standard room lights, actually; we didn’t set up lights at all to achieve those effects. Those were all happy accidents and clever blocking, but we also carefully curated our edit around them.

4. Listen-loo. looky-loo contains almost no dialogue and no extra-diegetic music, which brings a lot of attention to ambient noise, especially birdsong and other natural details. Why did you decide to handle sound this way? What effects do you expect this approach to have? How did you craft the script? Did you start with a lot of written direction for shot angles and cuts (such as the montages for welcome mats and keys), or did those elements evolve during production? What did the original script look like? How long was it?

NM: We wanted looky-loo to feel as real as possible, and we really struck gold with Casey Synesael, our sound designer. It’s kind of ironic that as sparse and raw as it is, the majority of the soundscape for looky-loo was meticulously engineered. So much sound was added afterward. Audience members get used to the nondiegetic sound in movies that the absence of it can be really jarring, and that seems to put people on edge. People tend to be more open to a good scare if they’re a little bit ill-at-ease to begin with.

The script was written at a frenzied pace. We knew there wouldn’t be dialogue or much in the way of overt characterization, so the first draft was a scant outline, which evolved into a fairly detailed outline, about twenty pages long. When we had a sequence coming up, Jason and I would talk on the phone a lot to bounce ideas back and forth about shots and just the logistics of how to achieve a certain effect, and in most cases I would write a detailed synopsis of that particular sequence. The script was extremely unorthodox, but working with our budget and accounting for unexpected mishaps necessitated that the script be as fluid as possible.

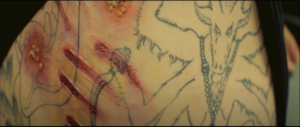

5. Psychology in Images. Looky-loo, as a character, isn’t merely a sadistic voyeur or a mindless stalker. Images of places he inhabits and of his behavior suggest a much more finely crafted personality. For example, after he kills his first victim, he partially covers her body in bed. How would you describe his personality? What motivates him psychologically, and what are other key images you can comment on (without spoilers) that reveal his inner motivations? For example, why does he have a relationship with a mannequin? Another quirky question—why does he include so many shots of cats?

NM: I’m glad you’re asking about this because the research that went into the killer specifically was beyond exhaustive. I had to become a serial killer expert because Looky-loo couldn’t just be a movie serial killer, he had to be the real deal. He’s an amalgamation of a dozen or so real serial killers. Looky-loo has serious issues with intimacy and a resultant deep animosity towards women. He also has a God complex like Ted Bundy: he believes wholeheartedly that he’s better than everyone else, that he’s smarter and more talented, and that his actions are completely justified. Given all of that, his relationship with the mannequin kind of makes sense, and it isn’t unprecedented, either. Jeffrey Dahmer also had a mannequin that he used to sleep next to so he wouldn’t feel lonely. Really, even the creepiest behaviors Looky-loo exhibits are all par for the course for serial killers. His apparent fondness for cats might be unusual, though–most serial killers are pretty unkind to animals. Really, I think Jason Zink is a cat whisperer because that wasn’t in the script. He just got swarmed by cats, so we had to use it. No kitties were harmed in the making of this motion picture.

“TAPEHEAD”

6. Fandominion. As I’m sure you know, a real community exists for VHS collectors, especially for people who collect horror tapes. How do you think most such collectors would react to “Tapehead?” The portrait you paint of the tape collector is sort of loving and sort of harsh at the same time. What are your own feelings about this kind of collecting, and what attitude toward collectors do you mean to convey?

JZ: I feel that it’s dangerous to take oneself too seriously, so you hit it spot on. My view of collectors is both loving and harsh at the same time. When I see people arguing over tapes online or hear from a fellow collector that someone sent them a death threat for having sold out of a tape they wanted, I get understandably upset and judgy. Nobody should treat collecting so extremely. But since some collectors do treat it so direly, I have a feeling that a small percentage would feel seen by TAPEHEAD and hate it. But I know more who see the silliness and recognize that we’re lovingly poking fun at the community, myself included.

7. They Just Don’t Make ’Em…. How do you feel about the actual movies you represent, such as Frankenhooker (1990) and Jack Frost (1997)? Did any movies of that sort influence you? Do you share in any of your main character’s nostalgia? In the closing credits, you show stacks and stacks of movies, some of which are real classics… why do you show the titles you show (some of them made me feel nostalgic)? Where did you get all those VHS boxes?

JZ: A lot of the tapes you see are my actual tapes. I grew up wandering the aisles of my local video store and marveling at the box art of films like Sleepaway Camp II: Unhappy Campers and Scream. I collected when I was younger, but I got rid of most of my tapes in college. During the pandemic, I got back into collecting in a big way, which is what inspired the short. I think that nostalgia can be a dangerous thing, and recognizing that in myself, I wanted to make something that was self-deprecating. It makes me feel more normal than the character when I have put myself into weird situations to find some of my holy grail tapes. And some of the tapes that we show are kind of in-jokes for other collectors. Like the Linnea Quigley’s Horror Workout tape, which he pulls off of the shelf at a Goodwill, because there is just about zero percent chance of finding one in the wild for ninety-nine cents.

8. Documentary Doctoring. As mockumentary, “TAPEHEAD” pokes fun not only at its subject but also at documentary filmmaking, all while using spot-on documentary style. Jason, you’re also attached to direct another documentary project, “We Destroy the Family: The Story of Lee Ving and FEAR.” What’s your attraction to documentary style? Do you see yourself playing with this style more in the future? What can you reveal about “We Destroy the Family?”

JZ: One of my favorite movies of all time is American Movie. I plucked that tape off the shelves of my local video store at a young age, and it left a lasting impact. Ever since, I’ve been drawn to the documentary format. Sadly, the hard truth is also that we have very little money to produce our films. So, a lot of our projects are written that way out of necessity. It just works out well that I have such an affinity for documentary and mockumentary films. I’m sorry to say that the “FEAR” documentary is in limbo. We completed a few interviews and filmed several of their concerts, but the producer has struggled to find the money to complete the film. It isn’t dead, but we needed to move on with other projects.

Night Terrors

9. Subgenres. Night Terrors is an anthology of three short films. It starts with “Massacre on 34th Street,” which is, as the title suggests, Christmas horror. Why do you think Christmas horror is such a phenomenon? Why do some people find Santa so charming when he carries an axe? The second short, “Baby Killer,” is extreme horror with a touch of sci-fi about a disgraced scientist working with stem cells, and the violence goes much farther than I expected. Why does this segment go so far, and do you see yourself going to extremes in the future? The final story, “Abstinence,” is also pretty extreme, delving into body horror. What drew you to body horror, and why do you think it has become so popular?

JZ: We made “Massacre on 34th Street” before we knew we were working on a feature. I just wanted to dip my toes into horror, and we found an old Santa mask at an antique shop, so we based everything around that. I also grew up watching Tales from the Crypt, so “All Through the House” was obviously an influence. “Baby Killer” was written and directed by my buddy Alex Lukens. Recently, we recorded an audio commentary for a 10th-anniversary release of Night Terrors. We both mentioned on that recording that we went to extremes we’re no longer comfortable with. I don’t regret any of it, but it just isn’t me (or him). At the time, I think that we were just trying to shock and prove something to horror audiences. In fact, Alex mentioned during that recording session that he was trying to overcompensate for his lack of horror experience, which is why it was so wildly written.

The question about body horror is a difficult one to answer. One of my oldest friends suggested a flesh-eating virus that spread through a college campus as an idea, so I ran with it. Living near a campus made it easy to imagine happening, and it basically wrote itself.

10. Fairytales. In the frame story for the short films in Night Terrors, the older sister refers to her stories as “old fairytales,” and while they’re not really old, they do all seem to have fairytale-like morals about behavior: Santa in “Massacre” seems more or less to go after people who aren’t so nice, the scientist in “Baby Killer” does forbidden stem cell research, and the horrors in “Abstinence” mainly strike the promiscuous. Are any of these morals serious? For example, what, if any, statement is “Baby Killer” making about stem cell research? Similarly, does “Abstinence” actually advocate for abstinence? Why or why not?

JZ: Wow, this is such an interesting set of questions. I don’t think Alex or I had ever considered those moral messages. At least not consciously. I can only speak for myself, but I don’t believe they are serious for either of us. Knowing that Alex only wrote “Baby Killer” to try to keep up with my tastes at the time, the film Inside being a favorite, “Abstinence” is the only one that carries any real message for me. While I don’t agree with abstinence-only education, I do think that safe sex and practical knowledge are hard to come by when you’re young and dumb. Growing up on movies like KIDS, sex was incredibly scary. So, while “Abstinence” takes those fears to the extreme, I don’t think it’s totally unreasonable to imagine something like this happening. Be safe out there, boils and ghouls.

About the Filmmakers

Jason Zink

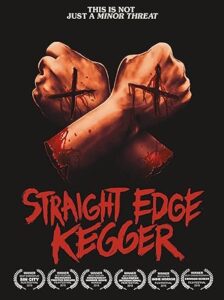

Jason Zink is a writer, producer, and director best known for Straight Edge Kegger (2019). After a successful festival run, Straight Edge Kegger obtained distribution through Scream Team Releasing and found its way onto Shudder, Amazon Prime, and TubiTV. Jason previously released Night Terrors (2014) and When I Die (2009). His forthcoming feature, looky-loo, is scheduled to be released on February 1st, 2025.

WEBSITE: https://www.weirdontoppictures.com/

INSTAGRAM: https://www.instagram.com/weirdontoppictures/?hl=en

FACEBOOK: https://www.facebook.com/weirdontoppictures/

TIK TOK: https://www.tiktok.com/@weirdontiktop

IMDb: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt27227397/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_0_tt_8_nm_0_in_0_q_looky-loo

STORE: https://screamteamreleasing.com/

VIEW THE TEASER: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jlp68LFXyPo

FACEBOOK (PERSONAL): https://www.facebook.com/weirdontopjay/

Nolan Mihail

Nolan Mihail is a writer, producer, and actor known for Peffersburg, OH (2019), Crawdad (2022), and looky-loo, which will be his first widely released feature film. When he isn’t working under the auspices of horror, Nolan writes and produces absurdist comedy shorts for his production company, Modern Travant.