The deluge of zombie fiction in the 21st century–variously attributed to millennial paranoia, post-9/11 trauma, stoked fears about border control and contagion, the influence of films such as 28 Days Later (2002) and Shaun of the Dead (2004), as well as novels such as Brian Keene’s The Rising (2003), and of course later phenomena including the TV adaptation of the graphic novel series The Walking Dead (2010 – present)–has created either an infinite feast of brains and viscera for the all-you-can-eat zombie fan or, for those of us who only have time for the tastiest morsels, a heckuva a hard time figuring out which movies to see and which books to read.

Enter Peter Welmerink‘s Transport. A quick glance at the premise–a military convoy traveling through a zombie-infested world–almost kept me from reviewing, as I’m a bit sick of zombies, and at least when indie and small producers/presses are involved, I decline to review rather than waste anyone’s time on a review that’s lukewarm or worse. (Before you rush to judge my policy as indie-biased, consider that silence can be worse than bad commentary.)

Enter Peter Welmerink‘s Transport. A quick glance at the premise–a military convoy traveling through a zombie-infested world–almost kept me from reviewing, as I’m a bit sick of zombies, and at least when indie and small producers/presses are involved, I decline to review rather than waste anyone’s time on a review that’s lukewarm or worse. (Before you rush to judge my policy as indie-biased, consider that silence can be worse than bad commentary.)

I’m glad that I gave Transport more than a cursory glance, however, because it is far more than a rehash of the military elements that show up in Danny Boyle’s viral fast-zombie opus, Romero’s Day, Land, and Diary, Brooks’s World War Z, and so on. In fact, one of the most delightful things about Transport is that the conflicts that recent uncountable zombie texts recycle are, for the most part, already worked out. Initial infection was a long time ago, and people have already (mostly) determined how infection spreads (differently from how you’d expect), so that part of the story–told hundreds if not thousands of times–is only a distant memory for Welmerink’s characters. Welmerink’s post-apocalyptic society has already started to restructure itself on a fairly large scale, so while journeying is still key to Welmerink’s story (more in a moment), Welmerink doesn’t need to rehearse the hopeless, doomed wandering of witnesses-to-the-end most familiar now from The Walking Dead but a staple of the genre for decades. He doesn’t even need to have characters face that awful “They’re us!” epiphany, as that particular realization has actually become a matter of widespread public policy debate.

In short, although Transport is the first in a series Welmerink has promised us, in a broader cultural sense, it is already a sequel to a story we’ve been hearing for awhile. And in that capacity, it is far more compelling than most of the zombie stories you’re likely to pick up.

Having made rehearsing the familiar largely unnecessary, Welmerink leaves plenty of room to introduce the unfamiliar, and building a new world is where his work is strongest. A slim volume, Transport introduces different types of zombies, other mutants, various political figures and belief systems, transformed landscapes, vocabulary for weapons and armor, and other details that emphasize ways in which the post-apocalyptic world surrounding Grand Rapids, Michigan differs from our own, details that justify the inclusion of a brief glossary at the book’s end. The presence of this glossary, along with the emphasis on diverse creatures, geographies, and peoples, fits better with the conventions of fantasy fiction that zombie-horror fiction, and indeed, Welmerink’s background is in fantasy/adventure rather than horror. The result of Welmerink’s approach is a successful hybrid I can only call zombie fantasy, a term that Welmerink seemed to like in our interview. Sure, the book offers exploding zombie guts galore, so hardcore horror fans will not be disappointed, but in addition to these structural features that are more like fantasy than horror, the book’s emotions, for me, are more based in excitement and wonder than in fear and disgust. Then again, sprays of liquefied intestines don’t really gross me out anymore.

The core of fantasy in Transport is inextricable from the journey–or road narrative–embedded in its title. Treated as an object rather than an activity, the title refers to the HURON, a rather impressive piece of equipment with an even more impressive crew carrying a rat-bastard political leader from point A to point E with every other point along the way holding a nasty surprise. Just as for Frodo and Sam going to Mordor, or more aptly, Roland, Susannah, Eddie, and Jake going to The Dark Tower, the journey itself is the true mission: it’s an inward journey of emotional transformation and an outward, picaresque experience in which each episode transforms both characters’ and readers’ perspectives.

Character transformations don’t appear in a lot of narrative soul-searching, however. Mostly, matters of the heart appear in how, when, and whom characters, especially protagonist Captain Billet, fuck up with choice ordinance. Welmerink leaves little time to mourn lost comrades or stumble into moral quagmires about which people to shoot in the face: his world moves too fast, and his people have too-important business. Welmerink’s style is hard-boiled to match, showing pain, attitude, and nonchalance in deceptively simple metaphors, as when, surprised by a question, the character “LaFleur jumped as if he’d just been kicked in the balls.” Eleven words: crisp image, sharp shock, sustained butchness appropriate to character. And just in case you’re thinking it’s nothing but a testosterone fest, balls aren’t the only power in the game. My favorite character is Phelps, an occasionally “enraged woman” whose “dark arms bulged with corded muscle.”

Character transformations don’t appear in a lot of narrative soul-searching, however. Mostly, matters of the heart appear in how, when, and whom characters, especially protagonist Captain Billet, fuck up with choice ordinance. Welmerink leaves little time to mourn lost comrades or stumble into moral quagmires about which people to shoot in the face: his world moves too fast, and his people have too-important business. Welmerink’s style is hard-boiled to match, showing pain, attitude, and nonchalance in deceptively simple metaphors, as when, surprised by a question, the character “LaFleur jumped as if he’d just been kicked in the balls.” Eleven words: crisp image, sharp shock, sustained butchness appropriate to character. And just in case you’re thinking it’s nothing but a testosterone fest, balls aren’t the only power in the game. My favorite character is Phelps, an occasionally “enraged woman” whose “dark arms bulged with corded muscle.”

Although I’m keen on the character development Welmerink offers, and he’s right to keep it secondary to the explosive action, I’d still like to see more dimensions emerge for each crew member, not just the Captain: action scenes work better with deeper investments in the actors. I also have to point out that while some of the sentences are just plain great, the book needs systemic editing, so the author might brush up a bit (an editor can only do so much). One last bit of constructive criticism–avoiding spoilers–near the end, a certain key event goes without much description, and giving us a look at it might strengthen closure, even if it’s a volume stopper (or a misdirect) rather than a series ending.

And now for a weird, me sort of thing…

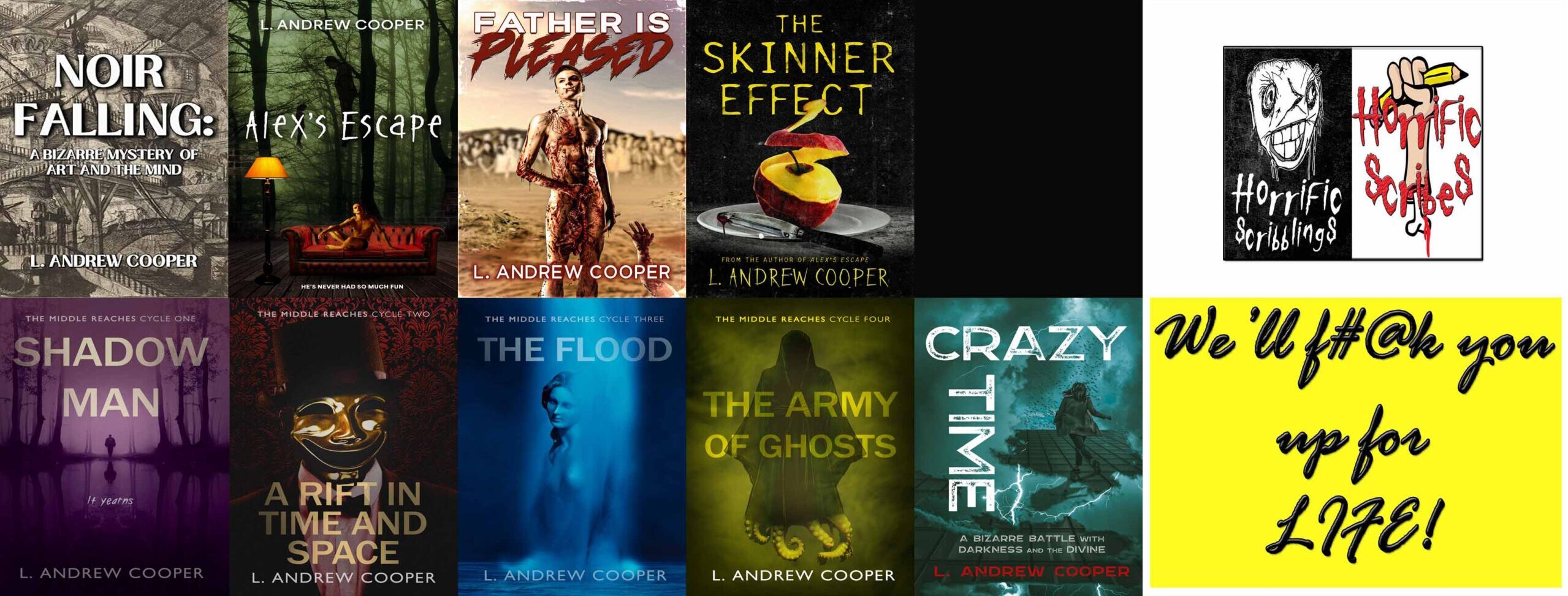

I have no idea if the author intended what I noticed, but one very cool thing about this book is its relationship not just with older media–other print media and film, as I’ve mentioned, and also comics, as one of the images from the book included here demonstrates–but also, somewhat intensely, digital games.The cast of ragtag characters on a road that has several stopping points, each of which contains an episodic adventure, resembles not only a classic picaresque but also the macro-structure of many RPGs, in which icons (the HURON?) move on a world map and then settle into more detailed environments at designated points, where characters fight, refuel, re-equip, and so on. Transport‘s narrative structure even builds toward what is arguably a boss battle with a super-mutant that has a shitload of hit points. Another frame for comparison for Transport, then, is the Resident Evil franchise, which spans print, film, and digital gaming media with a transportable (forgive the pun) premise involving an elite fighting group that faces zombies and mutants in an increasingly post-apocalyptic terrain.

I don’t mean for this comparison to belittle the innovation in Transport. In fact, I mean the opposite, as the similarity with Resident Evil‘s story that I’ve mentioned is only superficial, but the structural combination of elements from print, film, comics, and digital games in Welmerink’s novella (which I read in e-book format, increasing the media blur) makes it a fascinating sign of where zombie narrative, road narrative, and narrative in general might be moving. Even as it revels in pulpy aesthetics, Transport offers a view of the future in more ways than one.

Thanks for the great review. Gives me more food and fuel for thought and writing inspiration for the remainder.