I never even knew the guy, so I should focus on how Wes Craven changed American cinema, pretty much leading the post (or rather concurrent with) Vietnam horror-film response with Last House on the Left (1972), which puts the counter-culture in parallel with the dominant culture and finds them equally violent and disgusting, all while reworking Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (1960) to demonstrate that the idioms of art film and exploitation horror both have political (leftist) efficacy.

Thank goodness that while Mr. Craven still lived, Kendall Phillips perhaps best, but other scholars, among whom I might count myself, noticed that this man had made intellectual and artistic contributions to film and art history more generally that merit the thought of multiple generations.

However, my purpose here is not to offer a critical appraisal of how films such as The Hills Have Eyes (1977, the year I was born) and A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) defined modern horror, or how Scream (1996) resurrected it as a mainstream phenomenon, but to talk about ME ME ME, because I am really sad right now about the fact that MY Wes Craven is dead and I never even got to meet him.

It has a little something to do with my memory of taping popsicle sticks to my fingers and pretending to be Freddy Krueger when I was a kid (hi, Bruce!). I explain why Freddy became a hero of sorts at the beginning of my first published book, Gothic Realities, the early pages of which are free on Google Books:

BEGIN SELECTION

In a way this book, which officially started when I was a graduate student, really began at age nine, when I stole an opportunity to watch one of the 1980s’ most notorious horror films. I offer this brief account of a childhood encounter with Gothic horror as a case history, evidence that supports many of this book’s claims. The encounter was only possible because my friend Chris invited me to spend the night at his house; he had a basement where we could romp until the wee hours. The basement had a television, and the television had a cable box, so after Chris’s parents went to bed, we of course searched the channels for anything that might be forbidden. The most exciting thing we found was a movie, irresistible because it was rated R, that we had heard of but knew little about: A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). During the waking hours, nine-year-old-me tended to ignore what I knew about the consequences of watching scary movies, so I agreed to become acquainted with Freddy Krueger, the supernatural madman who murders children in their sleep.

I recall that when the movie got too scary, we switched channels until we thought the worst would be over, and we switched back inevitably in time to see Freddy’s razors ripping through someone’s flesh. Chris and I were giddy, exhilarated. We refused to go to bed that night not because we were scared (of course not!) but because we were having too much fun.

The next day I went home, and that night I went to bed when my mom told me to. Like A Nightmare on Elm Street’s characters, I felt terrified of going to sleep because I knew Freddy would be waiting for me in my dreams. When I closed my eyes, I instantly imagined him on the stairs leading up to my bedroom, brown hat, dirty sweater, and razor blades extending from a horrible gloved hand. Then I remembered how the movie ends: the teenaged heroine, Nancy, confronts Freddy and tells him he’s only a dream. She has the power; a kid could be stronger than a seemingly invincible psycho-killer. In the last chapter, this book discusses the ambiguity of the film’s ending, but nine-year-old-me wasn’t aware of any ambiguity. I remembered Nancy winning her battle against Freddy, and I thought that if she could, I could. I chanted to myself, “It’s just a dream, it’s just a dream,” and eventually I fell asleep. I didn’t have any nightmares that night. In fact, though I still have dreams both good and bad, since that night I have never been terrified of going to sleep.

Thus A Nightmare on Elm Street helped a child to overcome his greatest fears.

END SELECTION

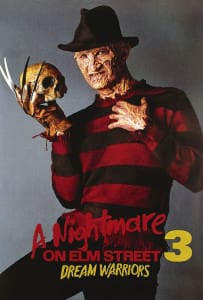

So in a way, I owe Wes Craven my childhood sanity, not that any of the kids I chased around with popsicle sticks would have known it. As a testament, this poster, from Nightmare on Elm Street 3, not Wes’s favorite film, I grant you, adorned my pubescent walls:

After the miracle on A Nightmare on Elm Street, however, seeing part three was the number one item on my wish list for my tenth birthday (I kept a literal list, and seeing the film in the theater received an extra star almost every time I saw the trailer with Patricia Arquette running through the house from the first film). When my parents gave in, the experience was MAGICAL. I of course identified with the boy in the wheelchair who played Dungeons and Dragons, but Freddy killing him brutally did nothing to change Freddy also being my hero. As Carol Clover has explained, that’s how horror films work, folks. I was everybody in those movies. I didn’t need to understand (yet) the subtle Hamlet joke in the poster I had hung with pride (riffs on Hamlet begin in the first Nightmare film, especially with the “I would bind myself in a nutshell and count myself the king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams” bit just before Tina appears in a body bag and a centipede creeps out of her mouth and such).

After the miracle on A Nightmare on Elm Street, however, seeing part three was the number one item on my wish list for my tenth birthday (I kept a literal list, and seeing the film in the theater received an extra star almost every time I saw the trailer with Patricia Arquette running through the house from the first film). When my parents gave in, the experience was MAGICAL. I of course identified with the boy in the wheelchair who played Dungeons and Dragons, but Freddy killing him brutally did nothing to change Freddy also being my hero. As Carol Clover has explained, that’s how horror films work, folks. I was everybody in those movies. I didn’t need to understand (yet) the subtle Hamlet joke in the poster I had hung with pride (riffs on Hamlet begin in the first Nightmare film, especially with the “I would bind myself in a nutshell and count myself the king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams” bit just before Tina appears in a body bag and a centipede creeps out of her mouth and such).

Wes Craven served up a festival of ME in the first Nightmare film, as I was most Nancy but also Tina and Glen and even a little bit Rod and also Freddy, and that festival kept playing in the inferior imitative sequels, and when Mr. Craven finally made his New Nightmare (1994), he showed me an image eerily similar to my childhood self with the taped-on popsicle sticks:

And with Scream, of course, he held up the mirror (psst, another Hamlet reference) to the film geek, un autre moi:

Most recently, when I wanted to express what I felt was the trap I was in because the University of Louisville could rob me of a voice because I have a mental disability, I thought of the centuries-old tradition of Gothic horror. I thought of Ann Radcliffe and the centuries of women who had used the Gothic as a language of voicelessness, and of men who had used the language as well, and the way to express my situation came to me as a story called “The Long Flight of Charlotte Radcliffe.”

If you’ve been reading my site for awhile, you might have caught the tale (at least a few thousand people did), but if you didn’t, I expect it’ll be in my collection Peritoneum, in print and e-book in 2016. The title refers, of course, to Ann Radcliffe, the pioneer of Gothic fiction whose stories usually revolve around women trapped by men whose legal power can overrule their will–a power paralleled today only by those who rule over people declared unfit to govern themselves–and as a result find themselves at constant threat of rape and murder. It also refers to Charlotte Bronte and by extension all the Bronte sisters, who tell stories of women dealing with overbearing men (I would have preferred a titular reference to Anne Bronte’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, the most traditionally Gothic of the Bronte novels, but another Ann(e) would not have been clear enough, so I settled for a better-known madwoman in the attic).

These women are fleeing, hence “flight,” but the story also takes place on an airplane, where my heroine is terrorized by a man in classic Gothic fashion–much like the heroine of Wes Craven’s under-appreciated Red Eye (2005), an extraordinarily intense thriller about a woman terrorized by a man in the claustrophobic space not of the Gothic castle but of the modern airplane. In one sense, I found the perfect metaphor for my situation that folded all of horror history into itself… but Wes Craven found it first. I part ways from Craven eventually, but without him, I would not have had a place to begin.

My philosophy of horror aesthetics and narrative hinges on the assumption that rational connections need not be established and in fact may be detrimental to desired affects. From whom did I learn such lofty notions? Ingmar Bergman, certainly. The dream-driven writing of Romanticists and their offspring, yes. But whom did I watch before all of them, whose work acknowledged them all, harnessed them all, and moved forward?

Wes Craven, RIP, 1939 – 2015, one of the greatest filmmakers who ever lived.

Comments are closed.